The first Martha Cooper Scholar in Photography, Dylan Mitro, has completed his residency year of study and development in Berlin. Along the way, he became more closely aligned with his identity as a documentary photographer, a storyteller, an archivist of history, and a member of the queer community. Looking back on his project of study hosted by Berliner Leben and Urban Nation Museum, he says his appreciation for social movements came into focus, as did his role as a photographer in capturing people and preserving cultural memory.

We spent a few hours speaking with him in the rooftop space atop the Urban Nation Museum talking about his experiences over the past year and looking at the materials that he created. We took away a few lessons on culture, art, preservation, and being present.

“Before I can be a person with a camera, I have to be a person they can trust… I cannot be exploitative, especially with communities that have been exploited so much.”

Photography Isn’t Just Style; It’s Witnessing.

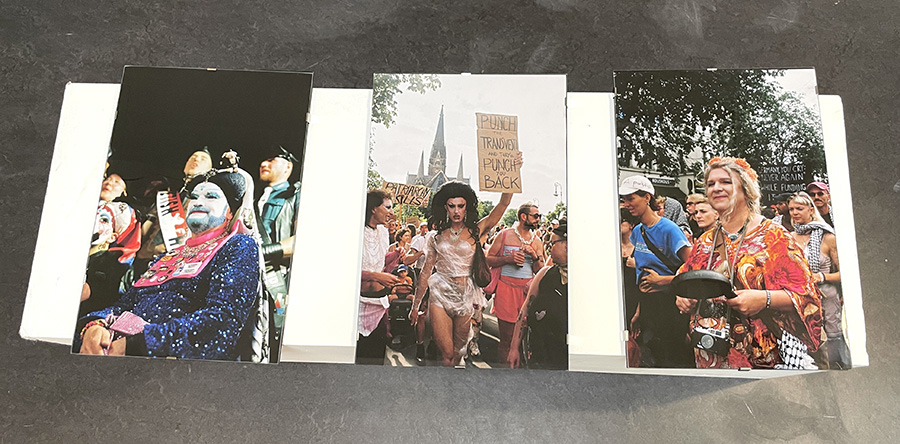

For Dylan Mitro, the camera has become less an instrument of aesthetics than a way of being present when history is unfolding before him. His “24 hours of protest” sequence of photos from animated and boisterous marches and demonstrations on the streets of Berlin is where this becomes clearest. He describes being in the street, whether raucous or quietly vigilant, with “thousands of people coming towards me,” running through the crowd and asking, “Can I take your photo?” as events unfolded in real time.

That sense of urgency and adrenaline is exactly what he admires in Martha Cooper’s work: her “always on” state, the way she treats the street as a field site and people as subjects rather than props. Dylan understands, as Martha does, that the most meaningful images are not staged or pretty; they are “honest and raw,” capturing people at protests, in queer nightlife, and in ordinary moments of showing up for one another. When he looks back at his protest images this year and says, “This is why I’m doing it,” he’s telling us that he recognizes that these fleeting, unposed encounters would otherwise vanish, leaving no trace in official records. Street photography through an ethnological lense, in his hands, becomes a way of witnessing courage and vulnerability in the moment and preserving it for those who come after.

“In the moment it’s so high energy, but then when you see the photos you’re like—okay, this is why I’m doing it.”

Archiving and Re-Photography are Acts of Care and Resistance.

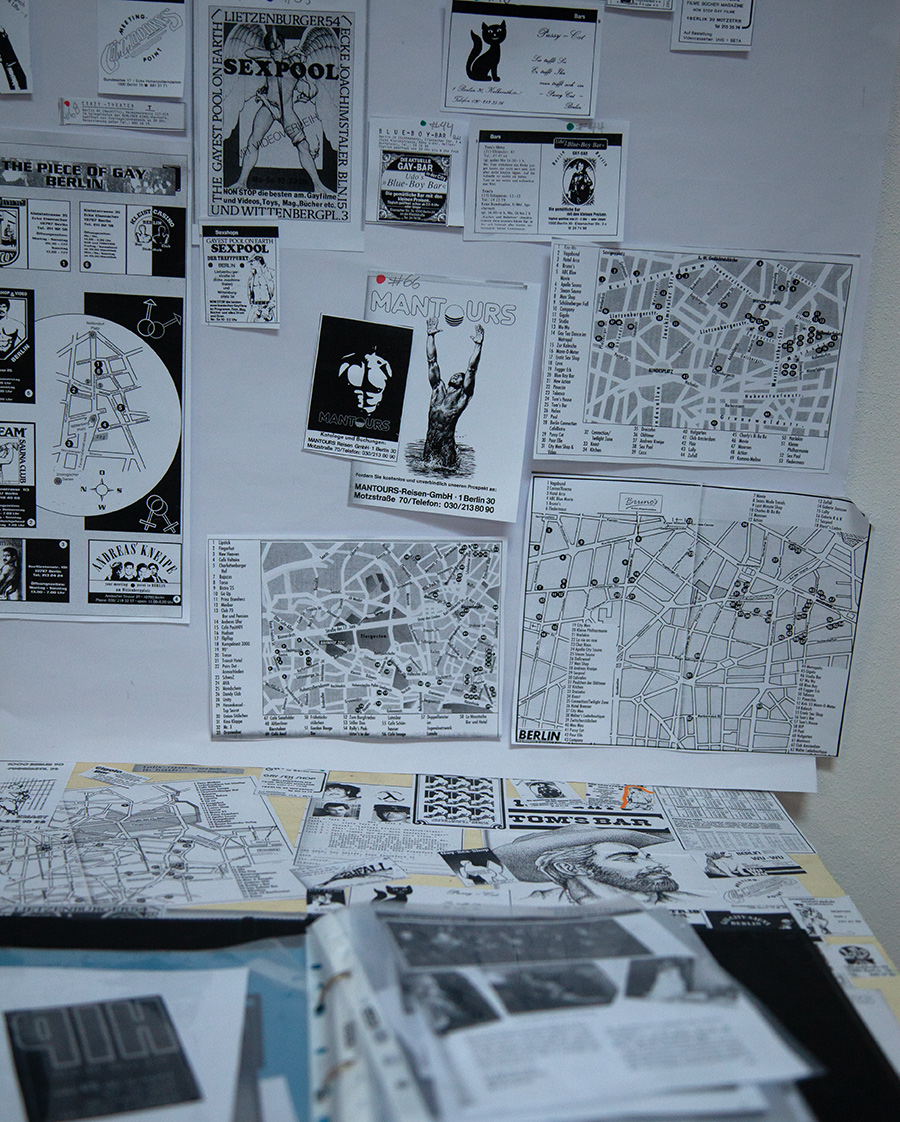

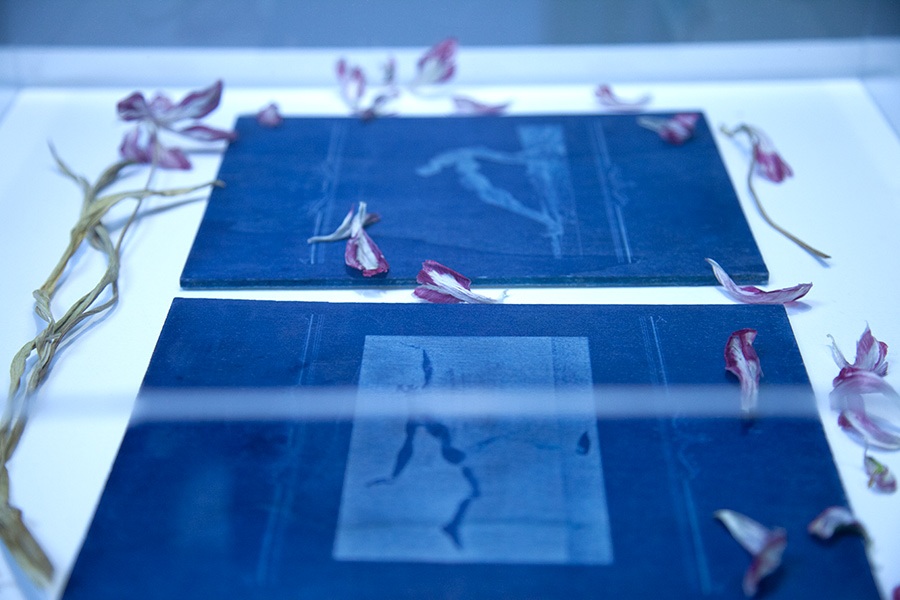

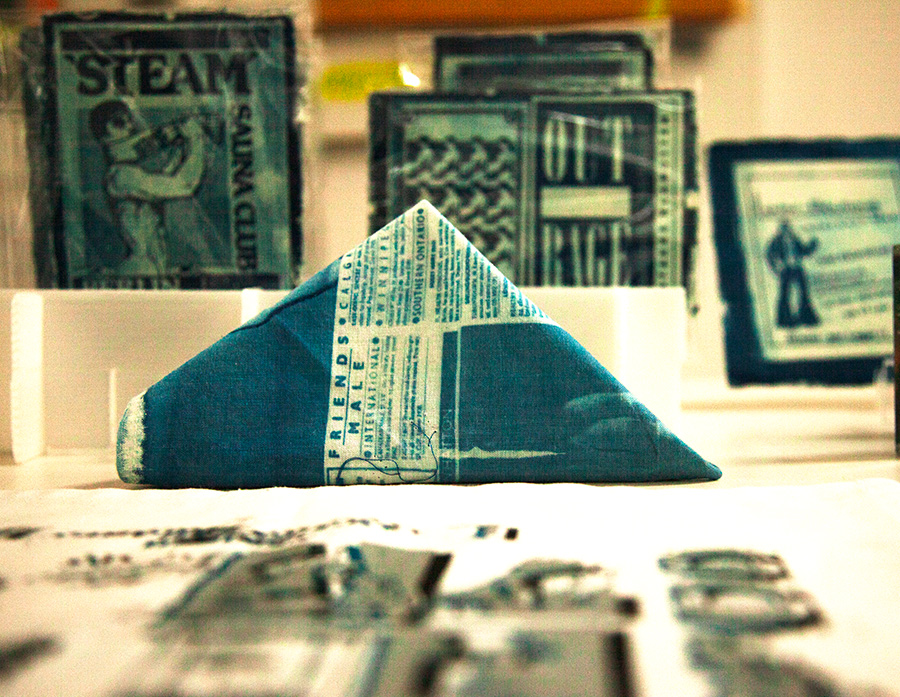

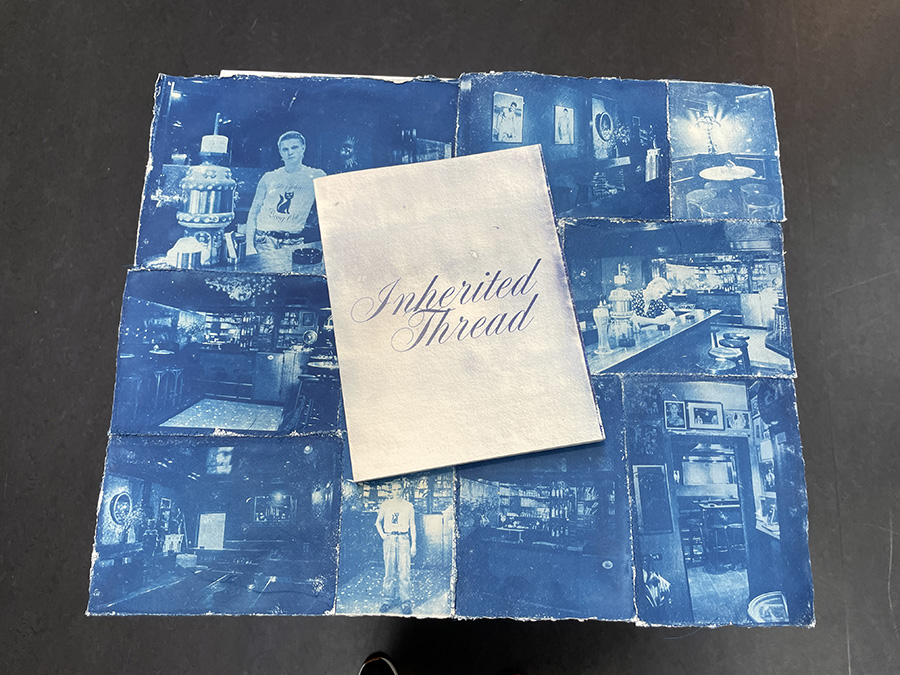

Dylan’s unconventional project of re-photographing and reactivating historic photos begins in the archive and brings people to speak to us here, now. He related his experience of making contact with private collectors of LGBTQ+ history and organizations who have documented queer history in Berlin, sifting through collections, commercial advertising, and personal stories without quite knowing what he was looking for. Possibly because people hid their identity for protection, some things were just out of reach, and Mitro related how images “appear… in this almost ghostly, haunting way.” From our perspective, this work looks like a fresh battle against erasure.

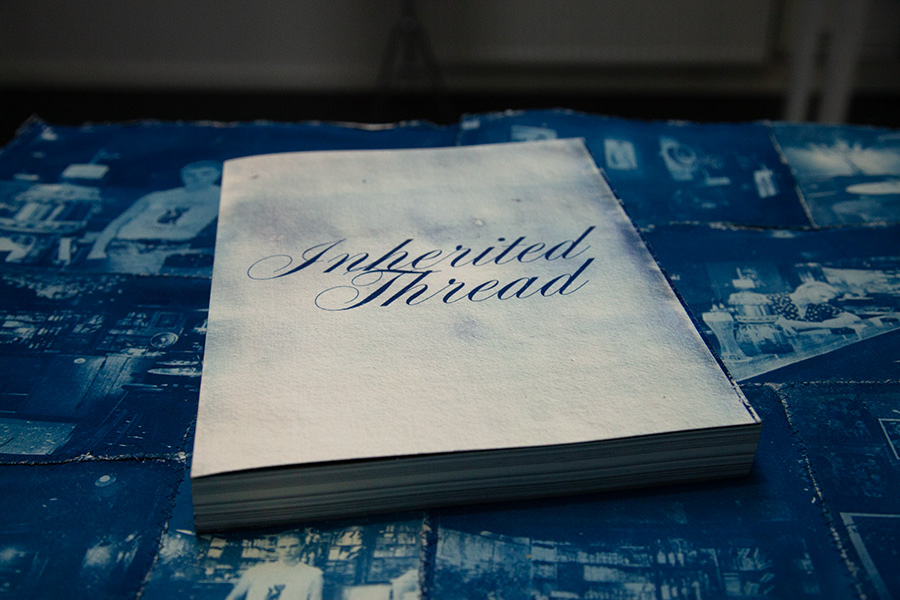

His research led him to retrace the locations of social clubs and bookstores and to pore over a varied and deep selection of printed and digitized materials at the LGBTQIA+ archives at the Schwules Museum in Berlin, including the publication Berlin von Hinten. Thanks to the careful collecting and preservation by many in the Berlin community, the artist says he found himself faced with an overwhelming array of diverse materials to study. Mitro brought his own scanner into the reading room, mechanically capturing pages to “deal with later,” making sure nothing important slipped past him in the flood. When he began making cyanotypes from sex journals, classifieds, and Berlin bar magazines like Berlin von Hinten, he was not merely appropriating images but changing their context and use, turning fragile, easily discarded ephemera into durable goods like book pages, prints, even shirts that he wore into the public and to the opening of his exhibition.

“The beautiful thing about an archive is you don’t know what you’re looking for when you go in, and then it just appears to you in this almost ghostly, haunting way.”

Thoughtful in his description of this self-created research process, he appears fully aware of an ethical minefield that he kept seeing in the materials: the sexualization of hustlers, questions of consent, the AIDS epidemic unfolding in the background, and the way one scandalous case can be used to demonize and smear an entire community. He also remarks on how much things have changed as queer culture has learned from its own past and become more equitable and inclusive. For him, to re-photograph, to print, to bind, is to refuse both erasure and simplistic moral panic. It is an act of care for those who lived through those years and a quiet resistance to the ways queer histories are flattened, censored, or selectively remembered.

Passing the Torch: How New Artists Build on Earlier Legacies

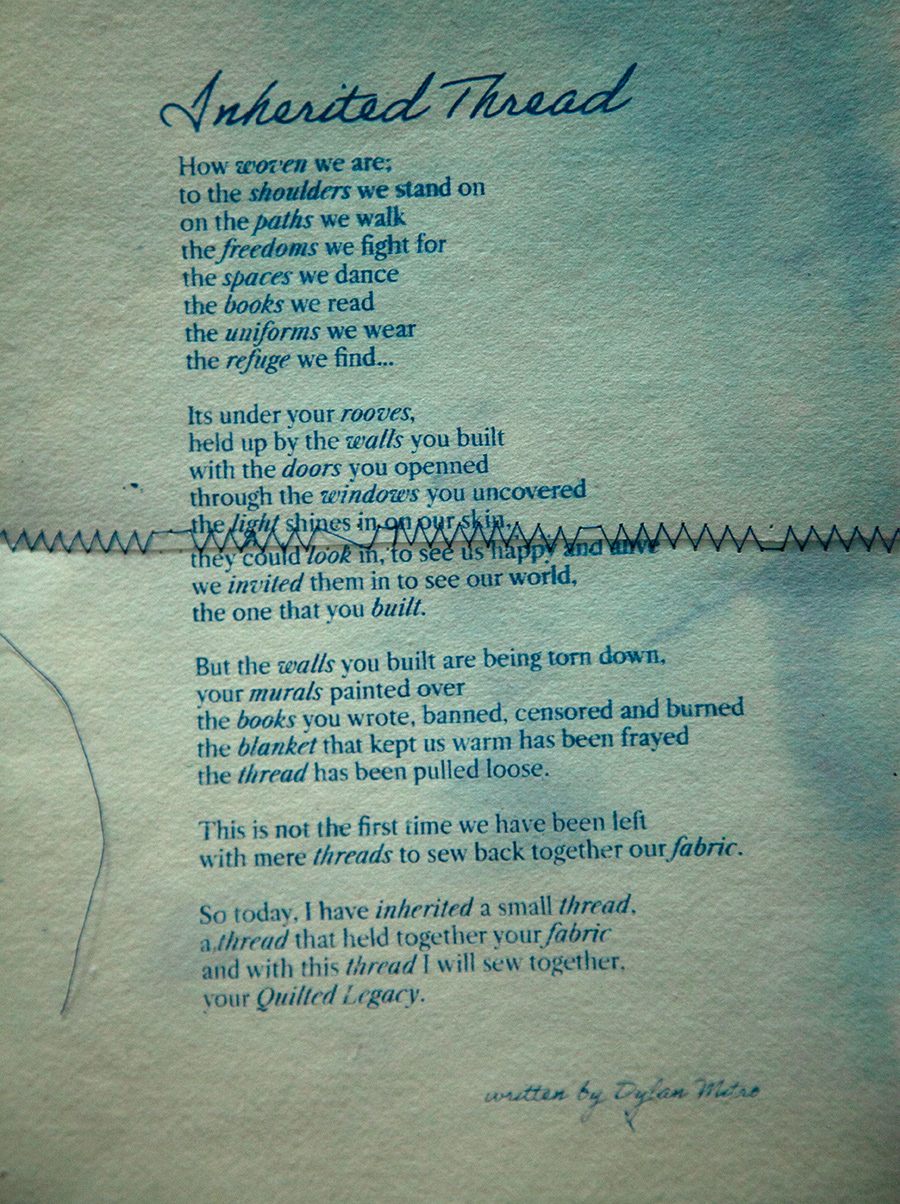

Dylan repeatedly frames his work as a kind of “grief politics” — a way to process his own grief and “collective grief” through images and stories. While he handles materials that can be considered crass, campy, or uncomfortable, he treats them as evidence of what previous generations built so that people like him can enjoy the relative freedoms they have now. During the conversation, we recalled that on earlier Zoom calls in the year, he talked about “recognizing the work that our ancestors have done… so we can enjoy the freedoms that we have now,” and he confirmed that this became central to his mission. In practical terms, this shows up in small but telling decisions.

Looking over materials and images, he noticed that many photographs in these magazines are uncredited or minimally credited; however, it was vital for him to reconstruct a credit page in his own book from the publication’s credit lists, even when he could not match each image to a specific name. He sees this as “doing the work for the crediting now,” anticipating a future researcher who might ask “who took this?” and refusing to leave them with a dead end.

His admiration for the photographer Martha Cooper is also part of it: he recognizes that she endured periods when her work was underappreciated, then gradually became a reference point for entire scenes and was treasured for their historical significance. By aligning his practice with her documentary, ethnological approach — attentive, long-term, grounded in real communities — Mitro is situating himself in a lineage of photography that tells our stories to each other and future generations.

When Time, Space, and Support Open a Path for an Artist

Dylan Mitro arrived in Berlin after a decade in Toronto, working punishing 14–15-hour days on commercial shoots and features, a rhythm he describes as “so unsustainable.” The residency allowed him to step off that treadmill and begin a course of study in a new city on another continent. He talked about the stark contrast: in the exact moment that he got the news about being selected for the residency, he learned the news of a close family member’s illness. As he talks, you realize that the year in Berlin became a hinge between these two realities — a chance to focus on his art and a forced confrontation with “what are these next chapters of my life?”

“It’s grief politics… how do I deal with my grief that’s also collective grief? And I deal with that in all of my work.”

With a new perspective, removed from Toronto, he considers that he cannot simply “jump right back into the way I was living.” While he regroups in Ontario and supports family, you can see that the residency gave him room to experiment: scanning archives, learning cyanotype techniques, organizing negatives by place, developing a whole book, and then pivoting mid-project to the “24 hours of protest” series that ties everything together. Along the way, he learned how to structure a day when nobody is calling call time, manage the pressure to enjoy and study the city, and answer the uncomfortable question he keeps coming back to: “Why are you doing it. The support he receives — from the scholarship, the residency, and mentors — may make it possible for him to build a thoughtful, ethically grounded body of work that he could not have assembled in the gaps between commercial gigs.

Reflecting: Photography as Proof of Life

Regarding his project, the cultural ground keeps shifting, and Mitro couldn’t have been more timely. In a political climate in the Western world where there is a backtracking on human rights and queer and trans lives are attacked and simplified, this kind of photography and archiving says: we were here, we are complex, and our images won’t disappear.

Throughout the conversation, Dylan connects his work directly to the present rise of fascism and reactionary politics. He notes that people now often say, “You can be queer anywhere in the city,” as if dedicated spaces and organizing structures were no longer necessary. He counters this by pointing back to history: earlier generations had to fight for those spaces and used them to manage when “the world kind of feels so helpless.” At the same time, he sees how quickly media and political actors can weaponize isolated events — a murder, a scandal, a stereotype — to brand entire communities as dangerous, from gay men in the 1990s to immigrants and trans people today.

That’s precisely why he went to the archive, sat with the original materials, and made new work grounded in lived experience rather than sensational headlines. His insistence on consent and trust in photographing protests, especially when working with trans folks, is part of the same refusal to flatten people into symbols. He’s acutely aware that much of the public visual language around queerness is still dominated by highly sexualized images, corporate Pride floats, and what he and the sponsors describe as “rainbow capitalism.”

By pairing reactivated archival images with new, candid protest photographs, Mitro constructs a more layered record: people organizing and dancing, grieving and celebrating, dressing up and just existing. In the shadow of book bans, anti-trans legislation, and cultural backlash, his project quietly insists that queer and trans lives are not a recent “trend” or a single issue to be voted up or down. They are entire worlds, spanning decades, and his camera — like Martha Cooper’s — is there to make sure those worlds are seen and remembered.

“I know I’m not going back to the life that I had before… I’m really reshaping how things are gonna be moving forward.”

Click HERE to read our first interview with Dylan, where he speaks in depth about their project Inhereted Thread for their Fresh A.I.R. Residency and the Martha Cooper Scholar for Photography 2025.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY