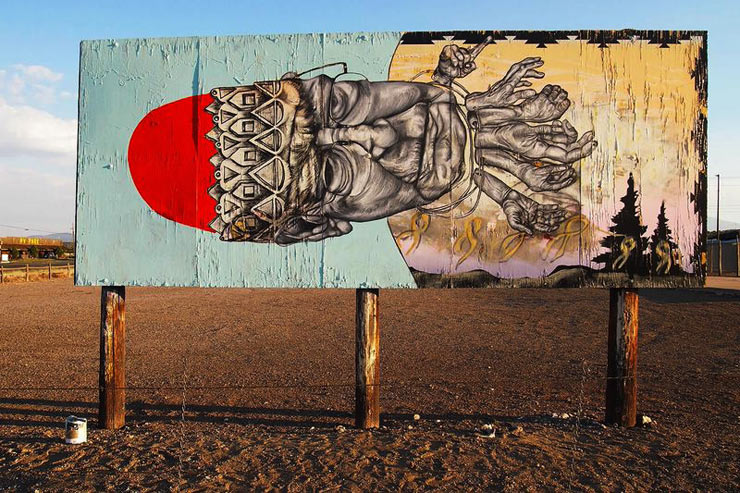

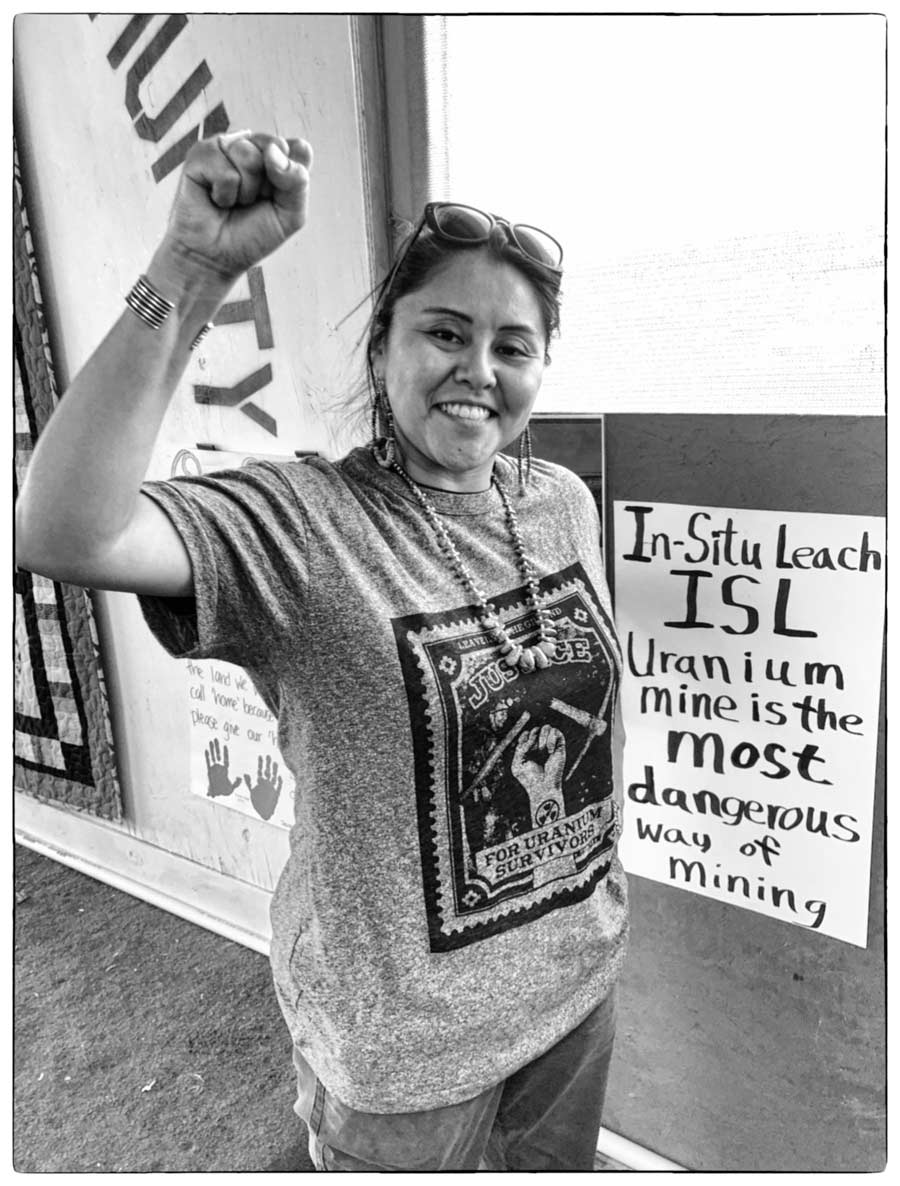

This spill and these events did not happen in San Diego, or Palm Beach. The story doesn’t affect wealthy white families and cannot be used to sell shampoo or real estate. That’s probably why we don’t see it in the press and never on the talking-head news. Street Artist Jetsonorama is not only a photographer who has been wheat-pasting his stunning images of people and nature on desert buildings for over a decade, he is also a doctor on the Navajo reservation, a human-rights activist, and an erudite scholar of American history as it pertains to the poisoning of this land and these people. Today we’re pleased to bring you this long-form examination from Jetsonorama’s perspective on a complicated and tragic US story of environmental poisoning and blight that affects generations of native peoples, miners, military personnel, and everyday people – and has no end in sight.

Most alarming is the news that current White House administration is endeavoring to mine uranium here again.

Stories from Ground Zero

Text by Jetsonorama

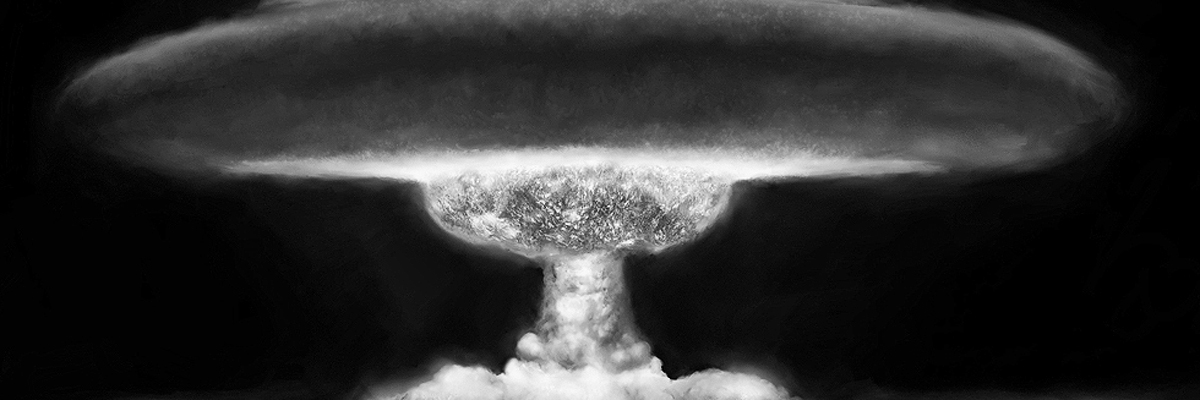

July 16, 1945 was an auspicious day in the history of humankind and the planet as the US Army’s Manhattan Project detonated Trinity, the first atomic bomb, in Jornada del Muerto, NM. (“Jornada del Muerto” fittingly translates as “Journey of the Dead Man” or “Working Day of the Dead.”) July 16 is also the day of one of the worst nuclear accidents in US history with the Church Rock, NM uranium tailings spill in 1979 on the Navajo nation (occurring 5 months after the nuclear reactor meltdown at Three Mile Island).

An earthen dam holding uranium tailings and other toxic waste ruptured releasing 1,100 tons of uranium waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive water into the Rio Puerco and through Navajo lands. Sheep in the wash keeled over and died as did crops along the river bank. According to a Nuclear Regulatory Commission

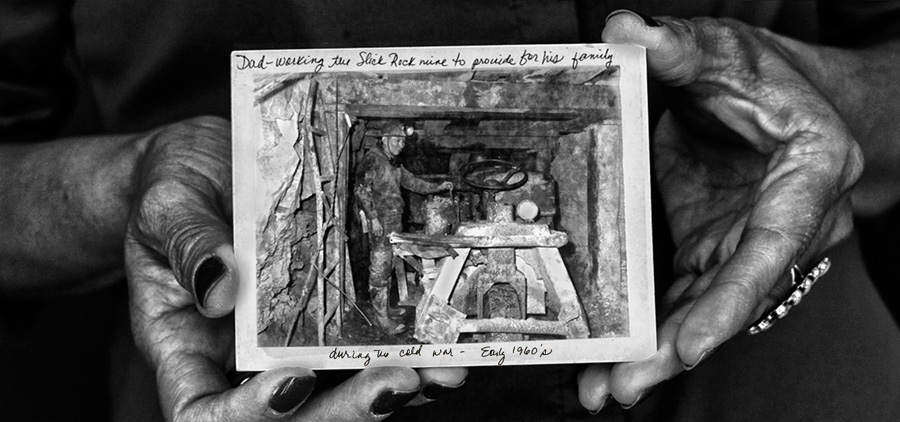

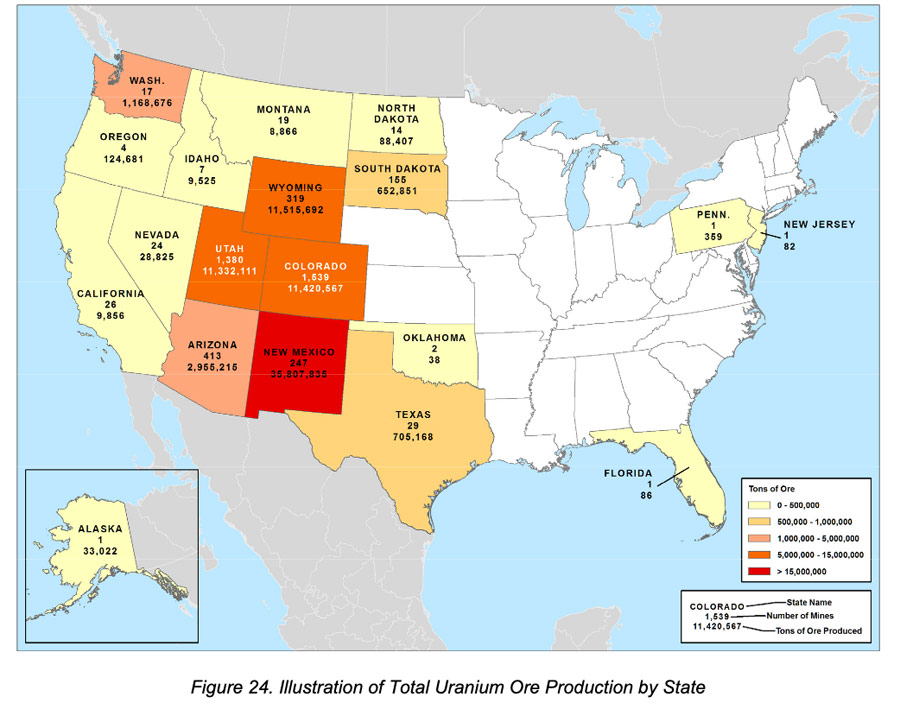

In an effort to end WWII and to beat the Soviets in developing a hydrogen bomb, uranium mining under the Manhattan Project began on Navajo and Lakota lands in 1944. Two years later management of the program was transferred to the US Atomic Energy Commission. The Navajo nation provided the bulk of the country’s uranium ore for our nuclear arsenal until uranium prices dropped in the mid 80s and is largely responsible for our winning the Cold War.

However, environmental regulation for mining the ore was nonexistent in the period prior to the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. During this time uranium mining endangered thousands of Navajo workers in addition to producing contamination that persists in adversely affecting air and water quality and contaminating Navajo lands with over 500 abandoned, unsealed former mine sites.

Private companies hired thousands of Navajo men to work the uranium mines and disregarded recommendations to protect miners and mill workers. In 1950 the U.S. Public Health Service began a human testing experiment on Navajo miners without their informed consent during the federal government’s study of the long-term health effects from radiation poisoning. This study followed the same violation of human rights protocol as the US Public Health Service study on the long-term effects of syphilis on humans by experimenting on non-consenting African American men in what is known as the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment from 1932 – 1972.

In May 1952 the Public Health Service and the Colorado Health Department publish a paper called “An interim Report of a Health Study of the Uranium Mines and Mils.”

The report noted that levels of radioactive radon gas and radon particles (known as “radon daughters”), were so high in reservation mines that they recommended wetting down rocks while drilling to reduce dust which the miners breathed; giving respirators to the workers; mandating daily showers after a work shift, frequent changes of clothing, loading rocks into wagons immediately after being chipped from the wall to decrease time for radon to escape and for miners to receive pre-employment physicals. Sadly, the recommendations were ignored.

By 1960 the Public Health Service definitely declared that uranium miners faced an elevated risk of pulmonary cancer. However, it wasn’t until June 10,

As high rates of illness began to occur workers were frequently unsuccessful in court cases seeking compensation. In 1990 Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act which seeks to make compensation available to persons exposed to fallout from nuclear weapons testing and for living uranium miners, mill workers or their survivors who had worked in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona between January 1, 1947 and December 31, 1971. An amendment to this bill is awaiting Congress after its recess that will expand years of coverage from 1971 to the mid 1990s as well as expanding the regions of the US covered.

At the other end of the life spectrum the Navajo Birth Cohort Study is the first prospective epidemiologic study of pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in a uranium-exposed population. The goal of the Navajo Birth Cohort Study (NBCS) is to better understand the relationship between uranium exposures and birth outcomes and early developmental delays on the Navajo Nation. It started in 2014 and has funding through 2024.

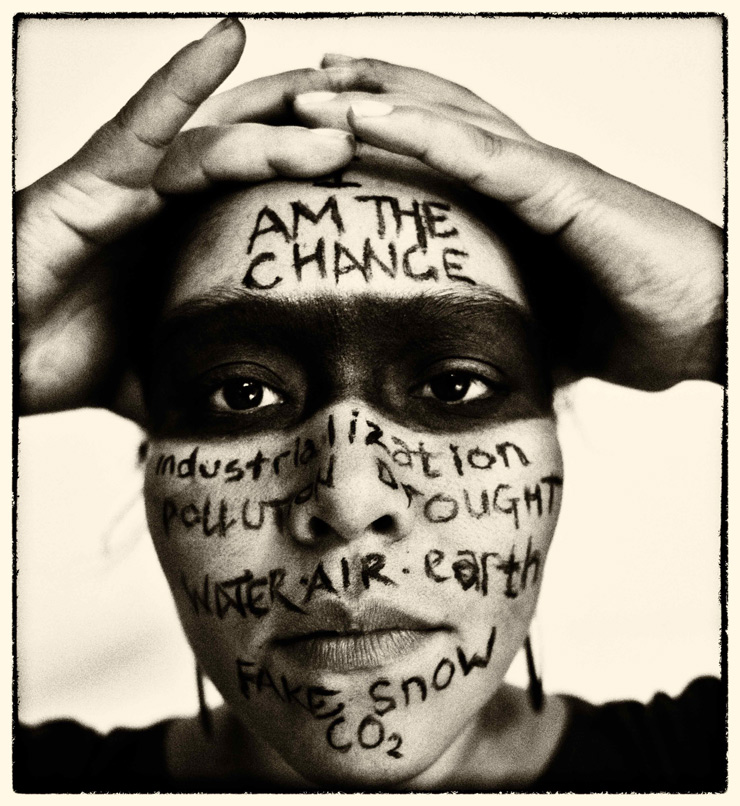

“As a heavy metal, uranium primarily damages the kidneys + urinary system. While there have been many studies of environmental + occupational exposure to uranium and associated renal effects in adults, there have been very few studies of other adverse health effects. In 2010 the University of New Mexico partnered with the Navajo Area Indian Health Service and Navajo Division of Health to evaluate the association between environmental contaminants + reproductive birth outcomes.”

“This investigation is called the Navajo Birth Cohort Study and will follow children for 7 years from birth to early childhood. Chemical exposure, stress, sleep, diet + their effects on the children’s physical, cognitive + emotional development will be studied.” (photo © Jetsonorama)

Efforts to mine uranium adjacent to the Grand Canyon have accelerated during the Trump administration. The most pressing threat comes from Canyon Mine located closely to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Because of the plethora of abandoned mines on the reservation the Navajo Nation banned uranium mining on the reservation in 2005.

However, it’s possible still to transport ore from off the reservation across the reservation. Approximately 180 miles of the Canyon Mine haul route would cross the Navajo Nation where trucks hauling ore had 2 separate accidents in 1987.

For more information on these and other uranium related issues at Ground Zero, check:

- www.facebook.com/nuclearissuesstudygroup/

- www.radmonitoring.org

- www.facebook.com/NIRSnet

- www.facebook.com/NukeWatch.NM

- www.indigenousaction.org

- www.grandcanyontrust.org

- www.stopcanyonmine.org

Additional links that further the story:

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY