Over the last two decades of covering the street art movement and its many tributaries, one of the deepest satisfactions has been watching artists take real risks, learn in public, and mature—treating “greatness” as a path rather than a finish line. Working at BSA, we’ve interviewed, observed, and collaborated with scores of artists, authors, curators, institutions, and academics; it’s been a privilege to see where they go next.

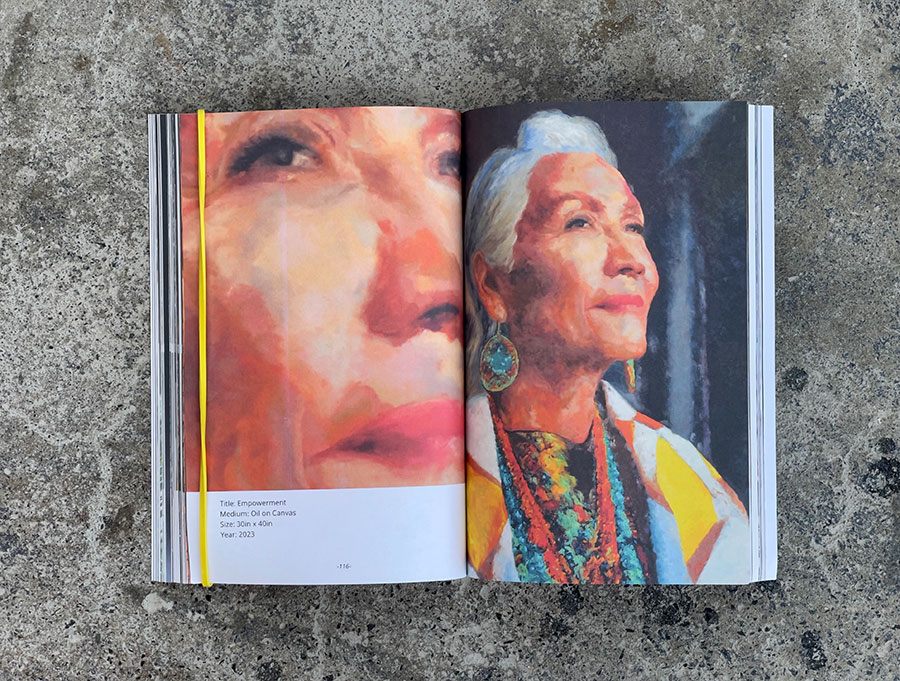

Addison Karl’s self-published 2024 monograph, “KULLI: A Natural Spring of Artwork, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Public Art, and Inspiration,” reads as a first-person chronicle from an artist who moved from the wall to the plaza to the foundry without losing the intimacy of drawing. Dedicated to his son—whose name titles the book—KULLI threads words, process images, and finished works across media: murals, cast-metal and glass sculptures, drawings, and studio paintings, all guided by a sensibility that treats color and material as vessels for memory and place.

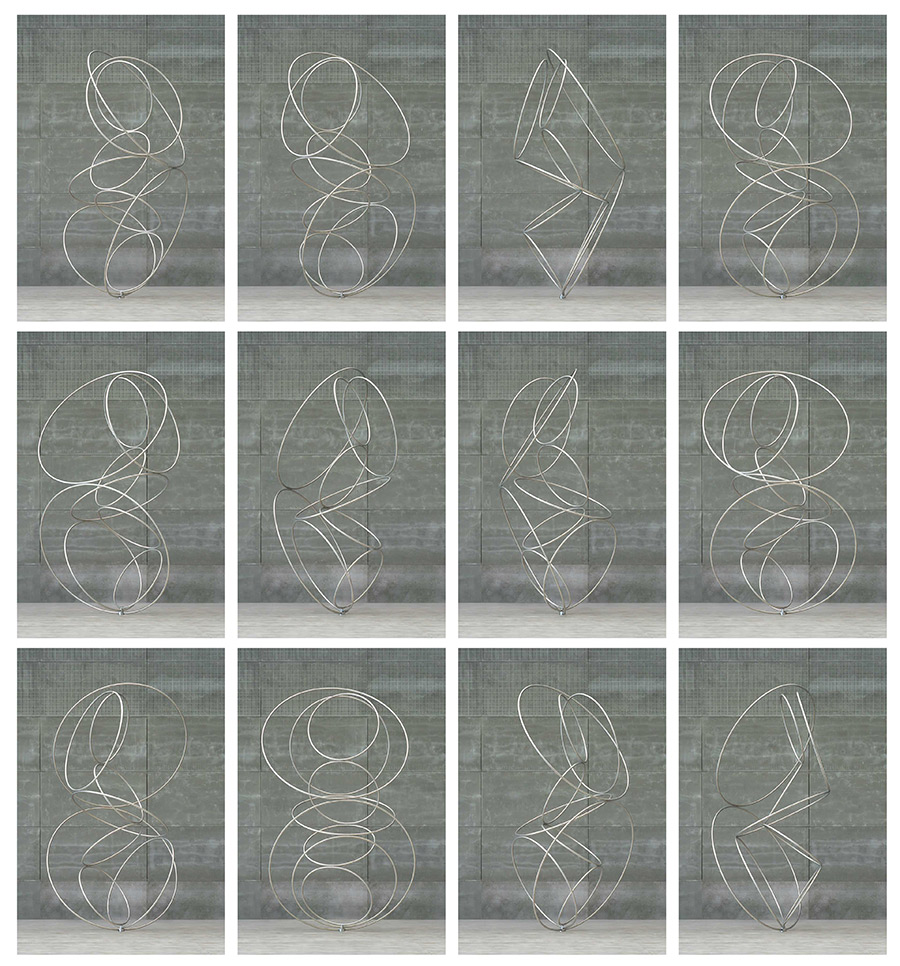

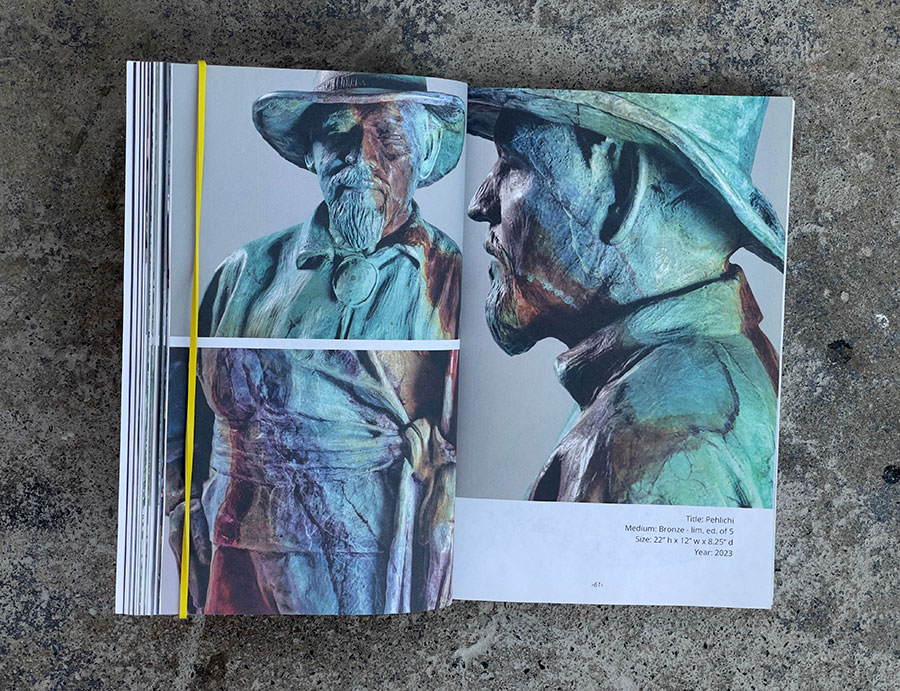

Trusted observers have mapped this evolution in plain terms. WALL\THERAPY once summarized Karl’s arc “from blank slate, to paper, to mural, to installation, to unoccupied public space,” a concise description of how a drawing-led street practice broadened into public art and beyond. The book situates headline projects within that trajectory: “In Service,” his 2019 McPherson Square Metro mural in Washington, DC—roughly 64 feet along aluminum panels—honors veterans, showing how a hand-drawn hatch can scale to civic form. In Atlanta, the cast-iron BeltLine sculpture Itti’ kapochcha to’li’ (“little brother of war”) roots contemporary public space in Chickasaw story and material logic.

Along the way, BSA documented Karl’s shift into sculpture and his view that public work demands accountability: “It makes you really understand the world in a really different way – of how you take responsibility for what you are doing.” Read together, these frames make KULLI a ledger of experiments—how a printmaker’s line climbed buildings, then solidified into bronze and glass—developed over more than a decade of international projects, including the opening of URBAN NATION in Berlin.

Crucially, the book lets Karl define his own stakes. “Each canvas is not just a painting; it’s a mirror reflecting the viewer’s own inner world,” he writes—an artist’s statement that clarifies why the outdoor work invites dialogue rather than spectacle. Biographical notes reinforce the point: Denver-born, Phoenix-raised, of Chickasaw and Choctaw descent, Karl’s foundation in printmaking underpins his cross-disciplinary approach; his patinas deliberately recall turquoise, and his public commissions translate personal narrative into shared space. Read KULLI as a record of that translation—how a drawing-based street practice consolidated a public voice and expanded into sculpture without losing the hand, the story, or the invitation to look harder.

Addison Karl. KULLI. A Natural Spring of Artwork, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Public Art, and Inspiration. Self-published. Monee, IL. 2024.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY