From the country with the highest standard of living comes a country-wide mural festival called UPEA for 2017! Only in their second year, they are going big here at home.

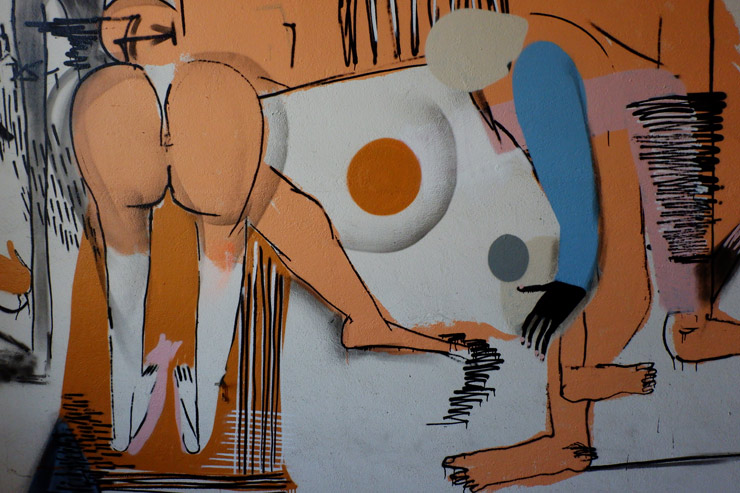

Messy Desk. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Markus Hänninen)

Okay, the murals are not in every city of this Scandinavian country, but if lead curator and visionary (and former graffiti writer) Jorgos Fanaris realizes his vision, there will be even more than the 40 or so murals the festival has already put up over the last two years in cities like Helsinki, Riihimäki, Kemi, Kotka, Espoo, Turku, and Hyvinkää.

Yes, some of the current international circuit of mural stars are here. So are a stunning selection of Finnish talents and less recognizeable names, making this a conscientious formulation that respects the culture and highlights the global movement simultaneously.

Guido Van Helten. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Erho Aalto)

Like many of today’s mural festivals and far from their illegal Street Art/graffitti roots, many of UPEA 17 are mega-murals; multi-story and sophisticated images borrowing from many strains of art history and popular culture – even conceptual art – as much as anything else.

These and other signs of curatorial/organization maturity are not typically hallmarks of two year old festivals, and we could provide a list of rookie mistakes that have plagued others we’ve covered over the last decade. This is probably because UPEA 17 is the result of many years of on-the-ground organizing experience and street culture knowledge – and multiple false starts and obstacles that blocked organizers in the years leading up to last years inaugural outdoor exhibition. People on the ground will tell you that logistics and costs and bureaucracy and local politics are always factors to pull off a festival well. In our experience, so is time.

Teemu Mäenpää. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

We were lucky to have an extensive interview with Jorgos Fanaris about this years successes, the challenges along the way, and his roots in the scene.

Brooklyn Street Art: How is UPEA 2017 different from the first edition?

Jorgos Fanaris: Compared to UPEA16, UPEA17 was of course much bigger. More artists and more projects, but also bigger projects. The first edition was more of testing the concept and feeling around what we could do. The second edition was really about making an impact, letting everyone know about UPEA as an event that creates notable art in public spaces, that we are serious and we are here to stay.

Millo. UPEA Festival 2017. Finalnd. (Photo © John Blåfield)

Brooklyn Street Art: You had an incredibly wide variety of artists painting: From large scale realist portraiture, to surrealism to cartoons, landscape etc…is there a specific style that resonates better with the public?

Jorgos Fanaris: The amount of talented artists that have already participated in UPEA in the first two years, is humbling to say the least. We are very privileged and honored to have had them.

If I evaluate the response the artworks have received from the public, I think raising a specific style in a position that it somehow communicates more with the audience wouldn’t be right. For example if we think realistic portraiture and classic style of Guido van Helten, its easy for anyone to understand that this is technically really difficult to execute in this scale. This year in Hämeenlinna we did the 56m high silos, which of course by the sheer size is something that makes people go “Whooaaaa, how can he do that? We must go and see”.

Dulk. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

The project gathered and still gathers spectators in huge numbers. During the project there were traffic jams in the area on Sundays. On the other hand in Lahti, the artist named Messy Desks did the crazy cartoon style piece that has million things happening. It created a huge buzz and received a lot of response from people. She was getting gifts from people from the area and was taken out for formal dinners after for appreciation and show of gratitude. Kids are ecstatic about it, knocking on the “doors” and “windows” trying to get someone to open.

At the same time, the second wall we did in Lahti with Roberto Ciredz, a surrealistic piece with total harmony, which by no accident is totally different from Messy Desks wall, was voted as people’s favorite of the two in local newspaper. There are so many things that contribute the overall feedback. I think every style and approach has its place and purpose.

Brooklyn Street Art: Murals become part of a neighborhood, part of the storytelling and lifetime benchmark associations and memories people have – as well as part of the fabric and character of a city. How has the festival been received by the people whose daily lives will be impacted with the presence of the murals?

Jorgos Fanaris: The artworks created a lot of excitement and grassroots movement in their own areas and communities. In Kontula Helsinki, the triple walls by Fintan Magee, Apolo Torres and Pat Perry encouraged the residents to do a “night of arts” event for the unveiling of the artworks. They had food, live music, fire performance and other artistic activities. Over 1500 people attended and possibly the event will continue next year.

Eero Lampinen. UPEA Festival 2017. Finalnd. (photo © Henrik Dagnevall)

In Espoo Matinkylä, where Artez did a great piece, the residents organized an celebration event with huge number of activities, dozens of performances and speakers, about thousand people attending the event. In Kotka, where Smug did the amazing wall right in the city centre, the city made an official unveiling for the wall by closing the street and having a horn orchestra perform. Hundreds of people attended even though it was on a Friday during the work hours.

These are just few examples. We saw a lot of these type of things grow from the artworks we did this year.. We see that street art gets reactions from people who might not be too involved with art in general, like going to the galleries for example. The artworks are a refreshing injection into the community and it’s super exiting for us to see things starting grow from them.

Onur. UPEA Festival 2017. Finalnd. (photo © John Blåfield-Valmis)

Brooklyn Street Art: Do you get support from community and city officials for the festival?

Jorgos Fanaris: Yes, we are working with the officials in every city we are in. The support has been great, possibly due to the fact that we have been able to create an event this size with fairly limited organization and funding.

Still the way we execute different projects really varies. Regardless of how much the city is involved, the permits, which are always a big thing in Finland, are handled by their own unit inside the city. In some cases the city assists us in the permit process and it can be very helpful. But also in many cases we handle the whole process completely. From searching locations and handling all the permits and other things all the way to executing the artwork. The range is very wide on different projects. Still, the city is involved and even if we are doing permits and related responsibilities ourselves, it helps that they are officially supporting the project in the background. Everyone has a common goal to make the project happen and in a positive spirit they work towards that goal together.

Onur. UPEA Festival 2017. Finalnd. (photo © John Blåfield-Valmis)

Brooklyn Street Art: What drives you to make this festival happen? What is the motivation? The incentive?

Jorgos Fanaris: Upeart is a collective of people from various backgrounds; from graffiti, city development to event organizing and more. I think the motivation varies depending on who you ask. But in general, it’s about interest in the possibilities art has in public spaces. The vision to push for ambitious ideas, pushing limits further and willingness to take chances.

I personally, have a graffiti background from late 80’s to beginning of the new millennium. When I painted myself, I was mainly, especially in the later years, interested in graffiti as a tool in getting reactions from ordinary people by using public space or things that move in that space. At some point, I moved away from actively painting and started working in music projects, doing shows and stuff like that.

During those years, Finland gradually started to dismantle the very strict zero tolerance on graffiti and street art they had imposed in the country for years. Many youth and grassroot organizations worked years relentlessly on it and it started finally to show some results around 2008. At some point, I thought the time would be right to start something like this. Do it seriously and professionally. We actually tried to start an ambitious project like UPEA for few years, but it was difficult. We had of course no money at all and with that also no guarantees about anything.

Ricky Lee-Gordon. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Rikupekka Lappalainen)

Then we tried to get a group of people together with the same goal to work on the project. With 3-4 people each contributing a little, combined, it creates an effort big enough to start an interesting thing – on paper at least. It proved to be very difficult. We had actually two tries that failed to make any progress.

We came together with a couple of people, agreed about the goal and how we should work towards it. But when it came down to doing real work for it – nothing much occurred. To me it was really strange. I feel that we wasted a lot of time and energy of course, and it was really frustrating. But eventually, probably after three years or something from the original idea, Upeart started to come together and this time with people who have the drive and are actually willing to work for it. So finally, the organization and the event UPEA was born on the third try.

Brooklyn Street Art: This is a very young festival, only two editions. Did you look at other festivals as an inspiration for UPEA?

Jorgos Fanaris: Yes, of course. You look around other festivals and different things that people do everywhere for ideas. I personally think that there are a lot of new and exciting things happening in several places around the globe. That’s why keeping your eyes open and trying to learn from everything is important. You see things and think, wow that’s so cool, could we do something like that? You add your own ideas in to it and it changes to something else.

Wasp Elder. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Matti Nurmi)

It’s a notable fact that UPEA is so young, like a little baby. We are not there yet and have huge task ahead of us on refining the concept. Already this year we wanted to do several other things besides murals, but we just didn’t have the resources to execute. But its ok, things always need time. The organization needs to grow, the concept needs to be refined and we need to build up our personal networks and several other things. In this process of maturing and finding the way for you, it helps if you see what else is going on around the world.

Brooklyn Street Art: What distinguishes UPEA from other European Street Art Festivals?

Jorgos Fanaris: I guess one obvious thing compared to many others, is that UPEA is a multicity event held all over the country. Finland is a small country, only 5 million people and the biggest city the capitol Helsinki, has only 1 million. When we thought about the concept, we really had to think about what will happen when we do a large number of big artworks and how it progresses when we do this year after year. We thought we would need serious space to execute on the level that we want year after year.

Apolo Torres. UPEA Festival 2017. Finalnd. (photo © Anna Vlasoff)

One thing of course also is that we have seriously big projects, especially on the second edition this year.

Considering we had the 56m high silos, triple side by side 8 story buildings, a complete house on all four sides and several single big 6-8 story buildings and so on, the sizes of the projects were huge. However now that we are looking forward at upcoming years, I think UPEA will become more and more original and mature to something very unique. Also one thing is, that several artists have told me, UPEA is one of the best organized events they have participated in. True or not (I think they are nice and say that in every event), I think this a proper note to end an interview!

Telmo & Miel. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Antti Ryynänen)

Telmo & Miel. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Antti Ryynänen)

Rustam Qbic. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

Rustam Qbic. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

Artez. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Kaukolehto)

Andrea Wan. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Jorma Simonen)

Smug. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tommi Mattila)

Vesod. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Anssi Huovinen)

Vesod. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Anssi Huovinen)

Roberto Ciredz. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Markus Hänninen)

Jussi27. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Anssi Huovinen)

Pat Perry. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

Fintan Magee. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

Jani Leinonen. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

Logos or graffiti tags? Jani Leinonen. UPEA Festival 2017. Finland. (photo © Tomi Salakari)

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY