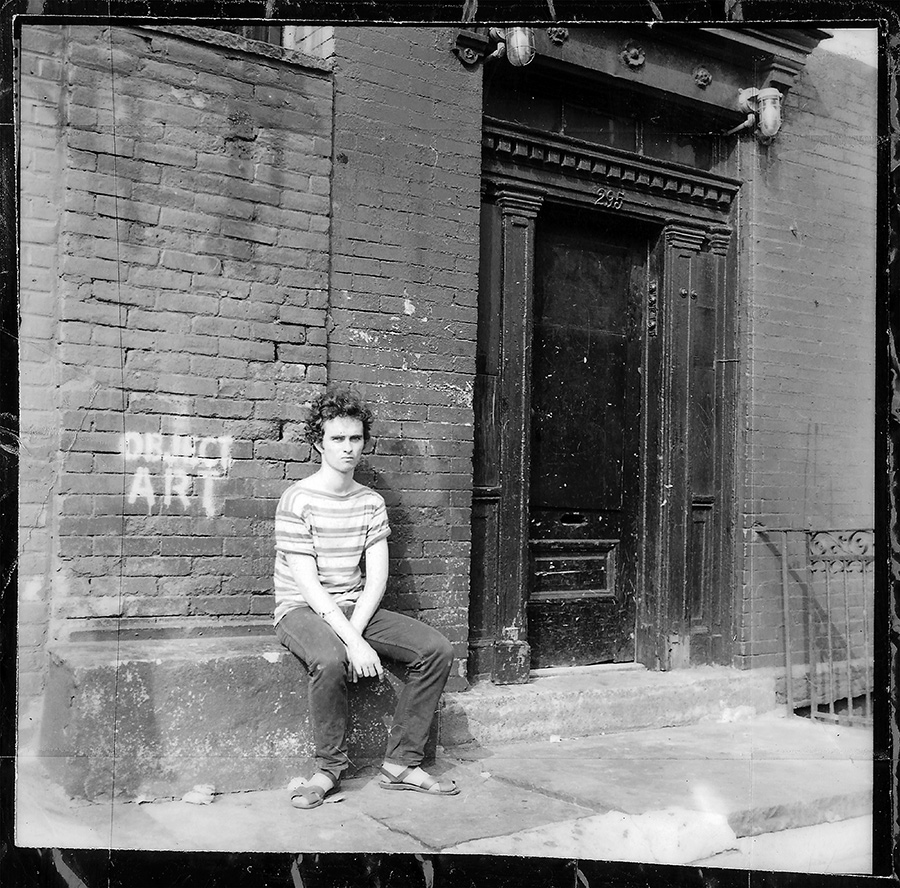

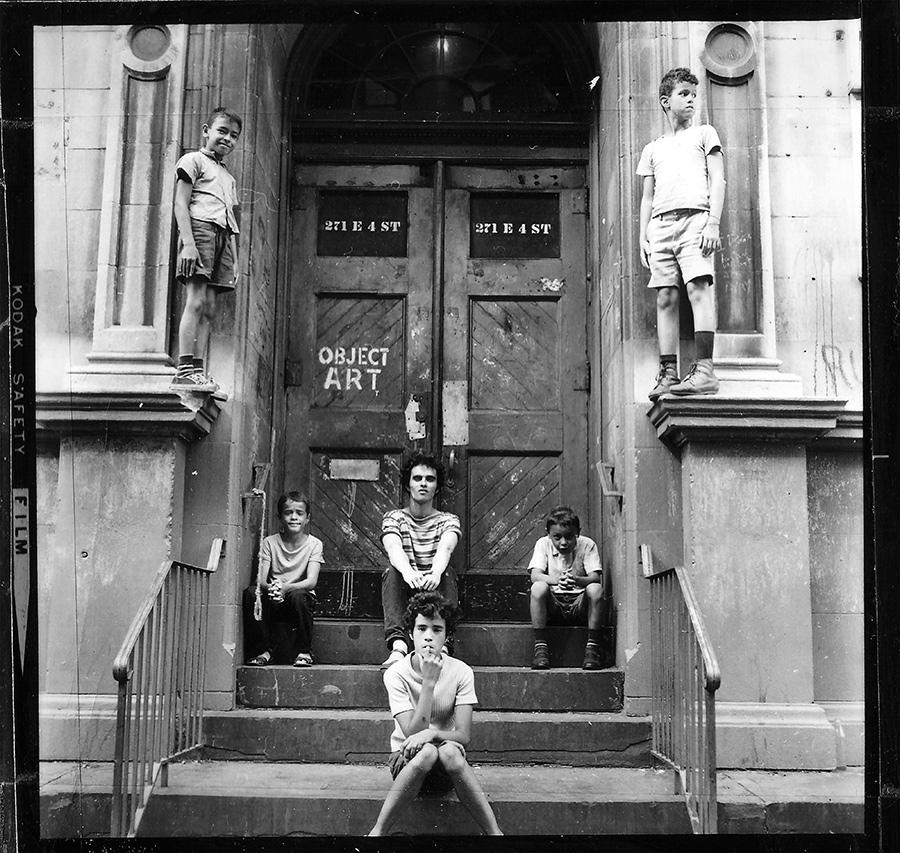

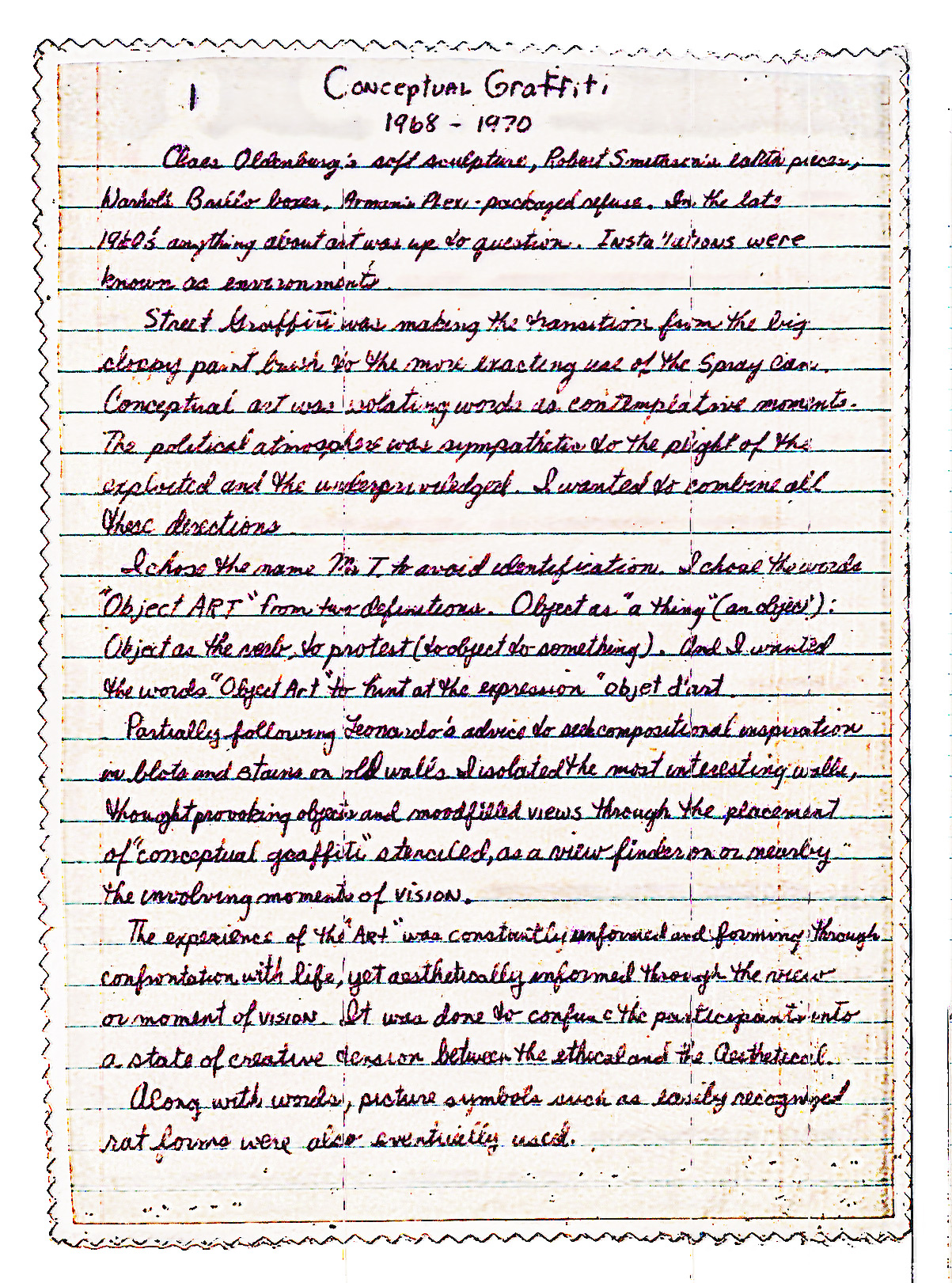

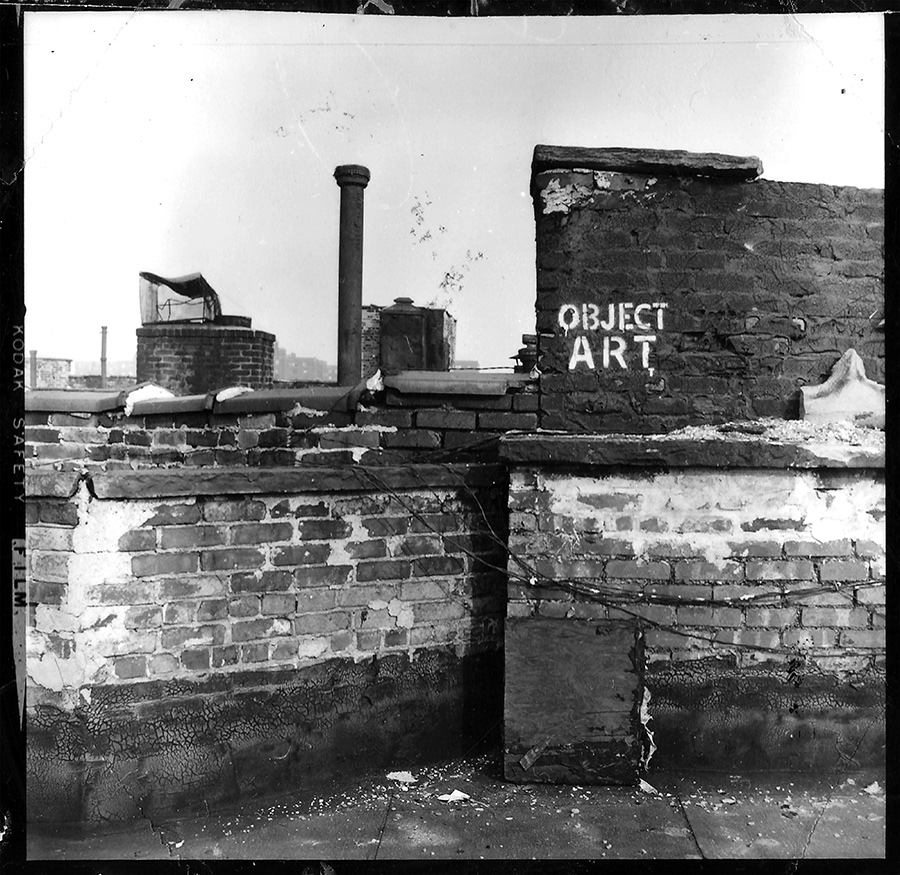

In the charged aftermath of 1960s protest movements, artists began taking their practices beyond galleries and into the streets, forging a new relationship with public space and everyday materials. The Situationists, for example, sought to interrupt the routines of daily life by wandering the city without a plan, using these aimless drifts to reveal the city’s hidden psychological and political layers. Around the same time, Gordon Matta-Clark carved literal voids into abandoned buildings, turning architecture itself into sculpture and critique. It was during this fertile moment, when early graffiti writers were claiming walls and conceptual artists were transforming the urban landscape, that Masao Gozu began his own quiet, obsessive project in New York. Though not street art in the conventional sense, Gozu’s decades-long practice of photographing and reconstructing building façades from the Lower East Side resonates with the same spirit: using the city itself as subject, surface, and raw material. In the essay that follows, artist and curator Ted Riederer—who first met Gozu while directing Howl! Happening—offers an intimate portrait of an artist who transforms dereliction into devotion, and time itself into sculpture.

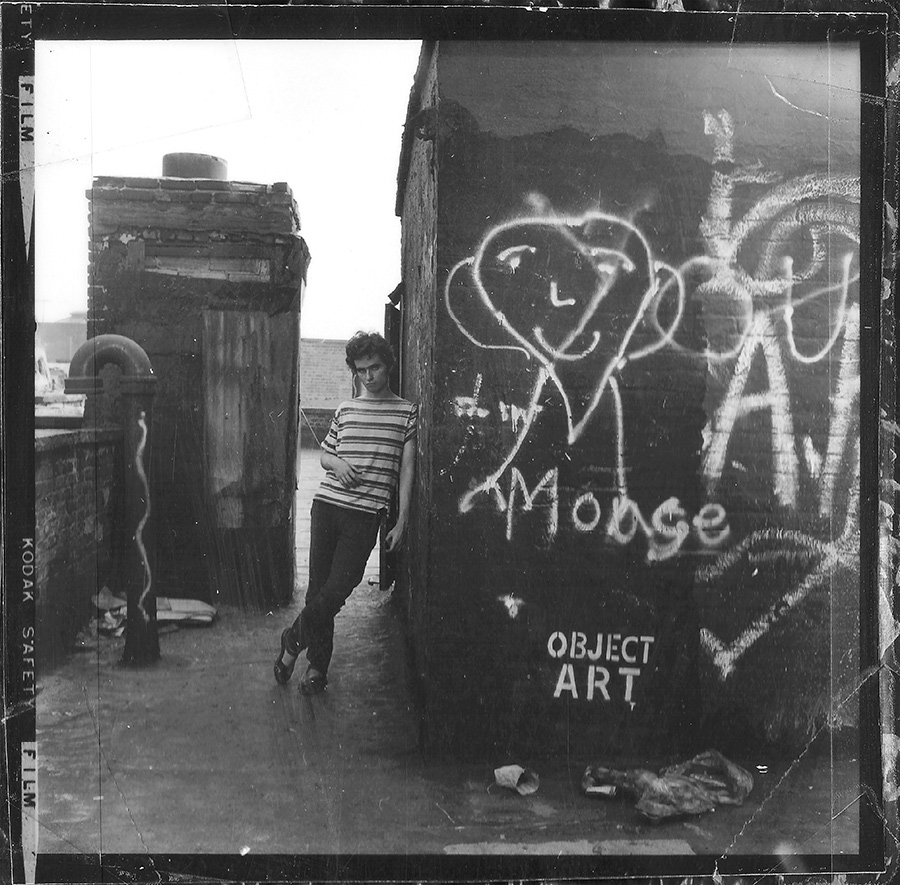

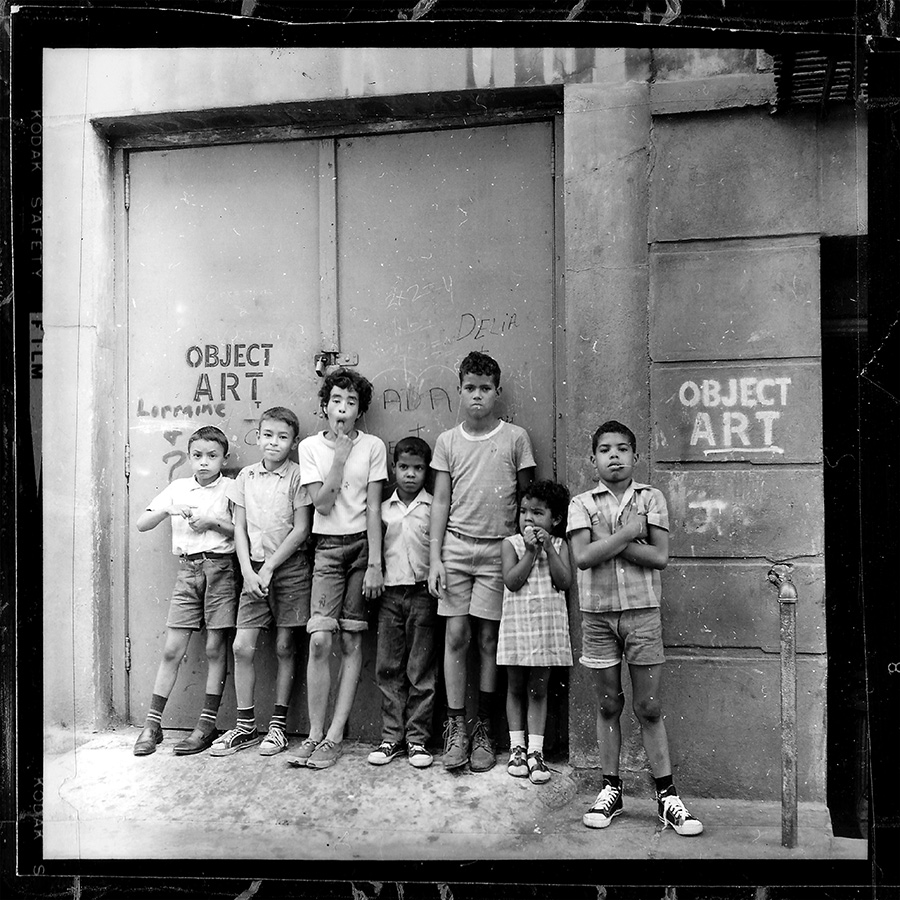

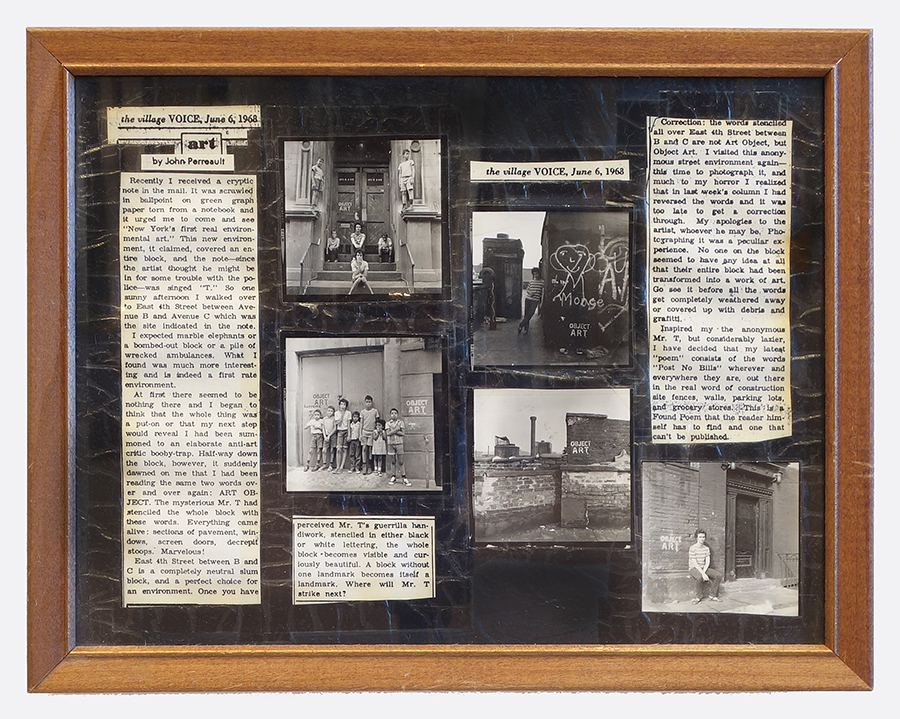

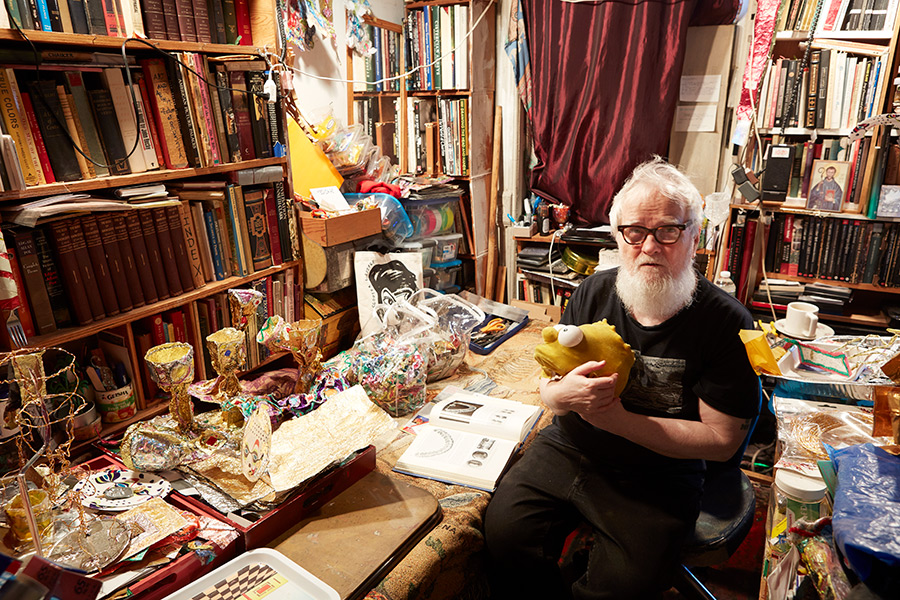

During the Pleistocene 1970s and 80s, New York street art culture coalesced into a variegated art form. What began with simple tags ended with museum exhibitions. In the early 80s, when East Village street artists were painting and posting on derelict buildings, Masao Gozu was disassembling them and reconstructing them into monuments. I first met Gozu when I was the artistic director of Howl Happening: An Arturo Vega project. We mounted his exhibition Timeframe in the Fall of 2017. I was awestruck by his all-encompassing quasi-spiritual devotion to his work. Piece by piece he dismantled abandoned buildings. Piece by piece he methodically rebuilt them in his studio. In disassembling and reassembling a puzzle of bricks, he was in search of a fleeting moment in time. His work is not street art, rather art made with the streets.

Born at the end of WW2, Masao Gozu grew up in rural Nagano, Japan, where his family had lived for ten generations. Like many other artists his age, Gozu was discouraged by what he perceived as a lack of opportunity in the reconstruction and occupation of post-war Japan. He applied to art school in the United States as an escape and was accepted into the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

There is an under-reported history of Japanese artists contributing to the vibrant downtown art scene in New York during the 1970s and 80s. Artist and friend Toyo Tsuchiya, who moved to New York in 1980, attributed his own immigration to an enticing article about the New York art scene published in the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo. Unable to relate to the stiff, formal academic art world reigning in Japan during these years, Tsuchiya described arriving in New York and being quite surprised to find an established and thriving community of avant-garde Japanese artists on the Lower East Side, centered for the most part, around Kazuko Miyamoto’s Gallery Onetwentyeight.

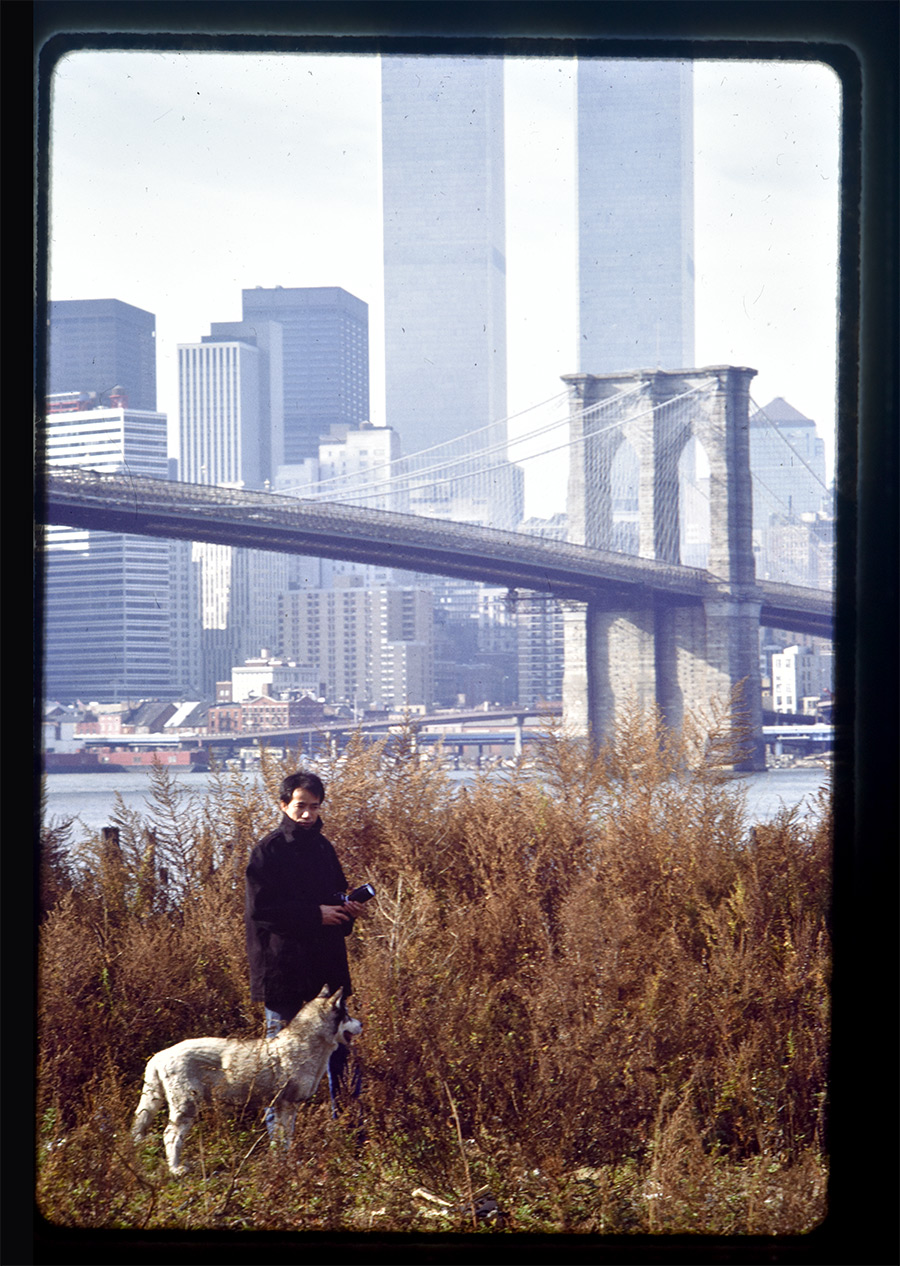

Penniless and alone, Gozu had moved to Brooklyn in 1971. At the Brooklyn Museum Art School he studied under Reuben Tam, a landscape painter. Through this community, Gozu found other artists who helped him find work and housing. 1971 is also the year he began taking pictures of windows.

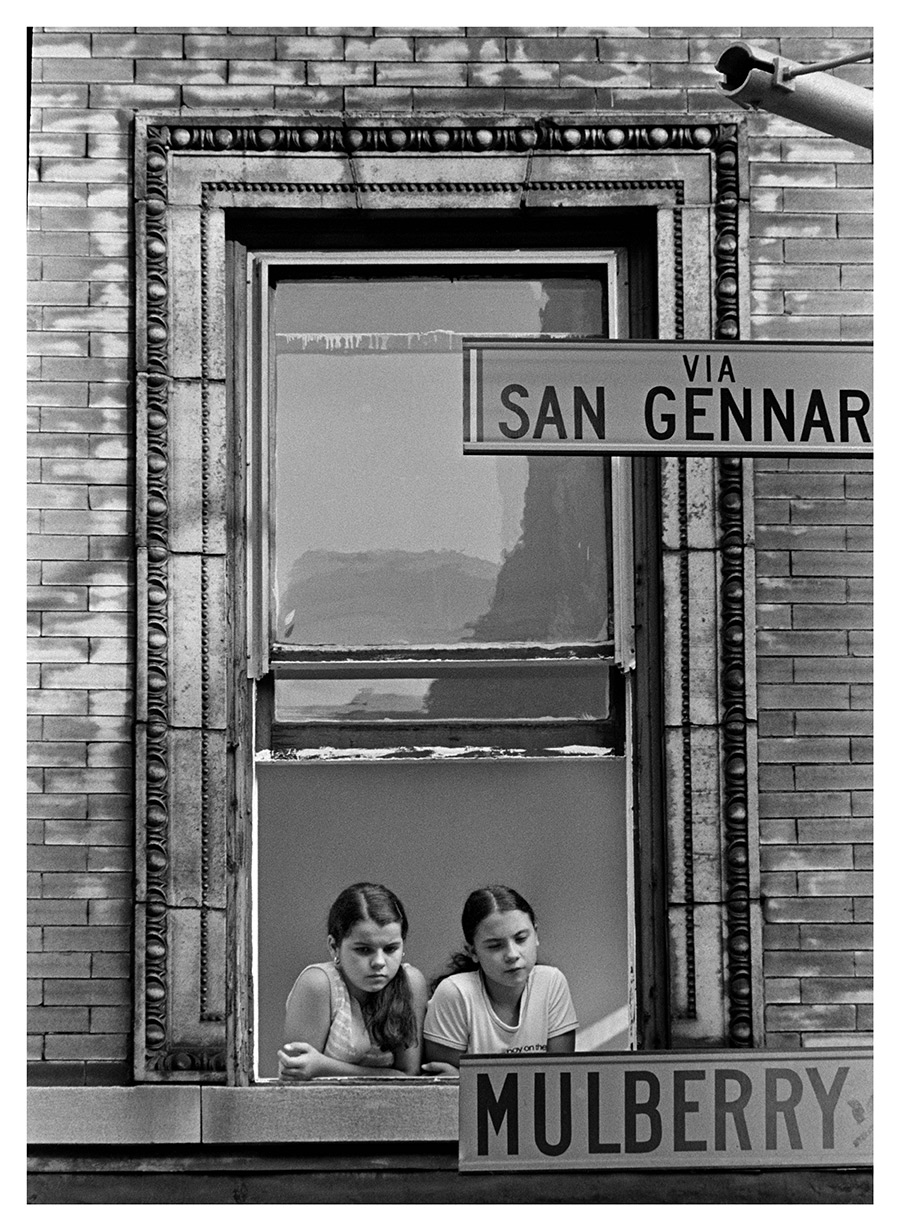

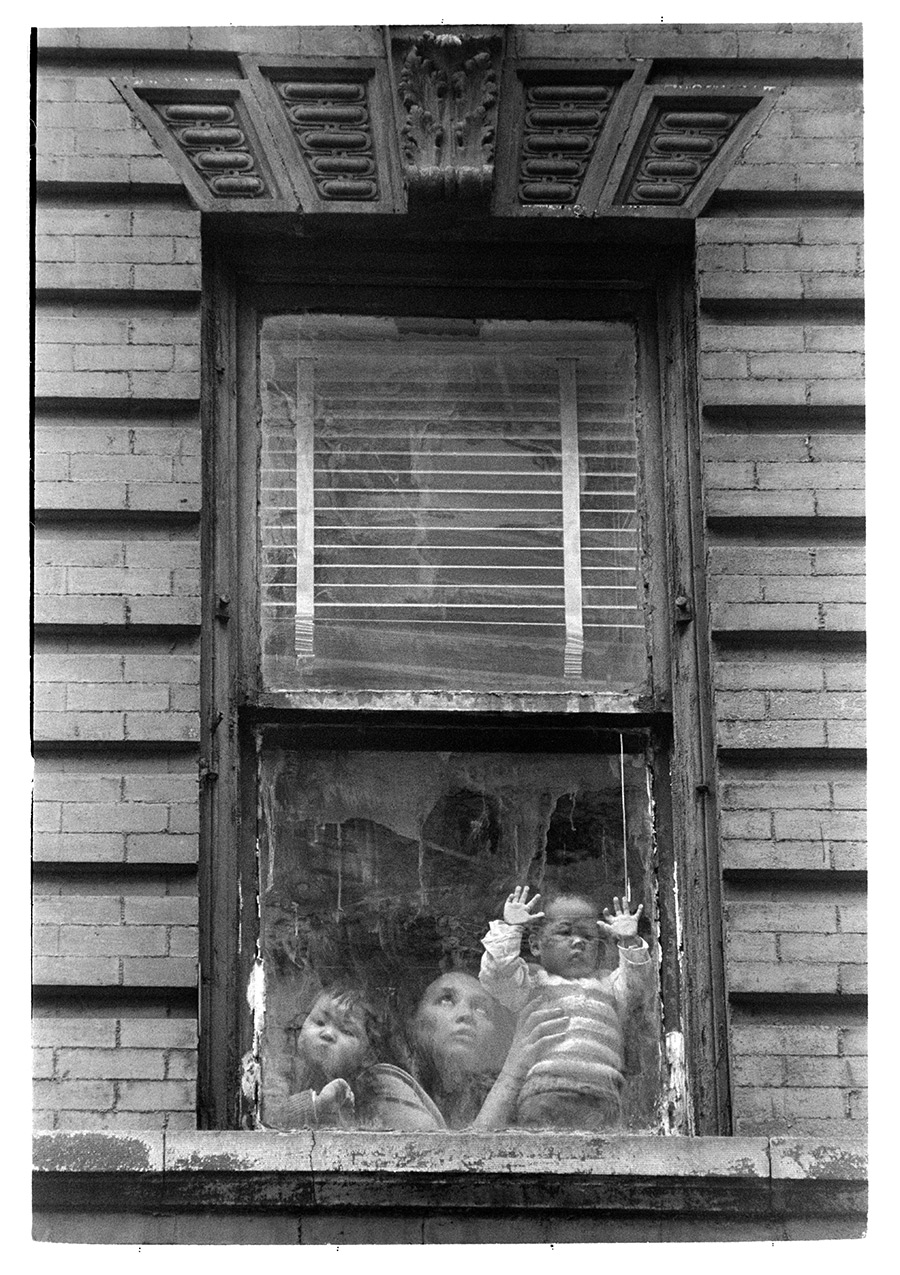

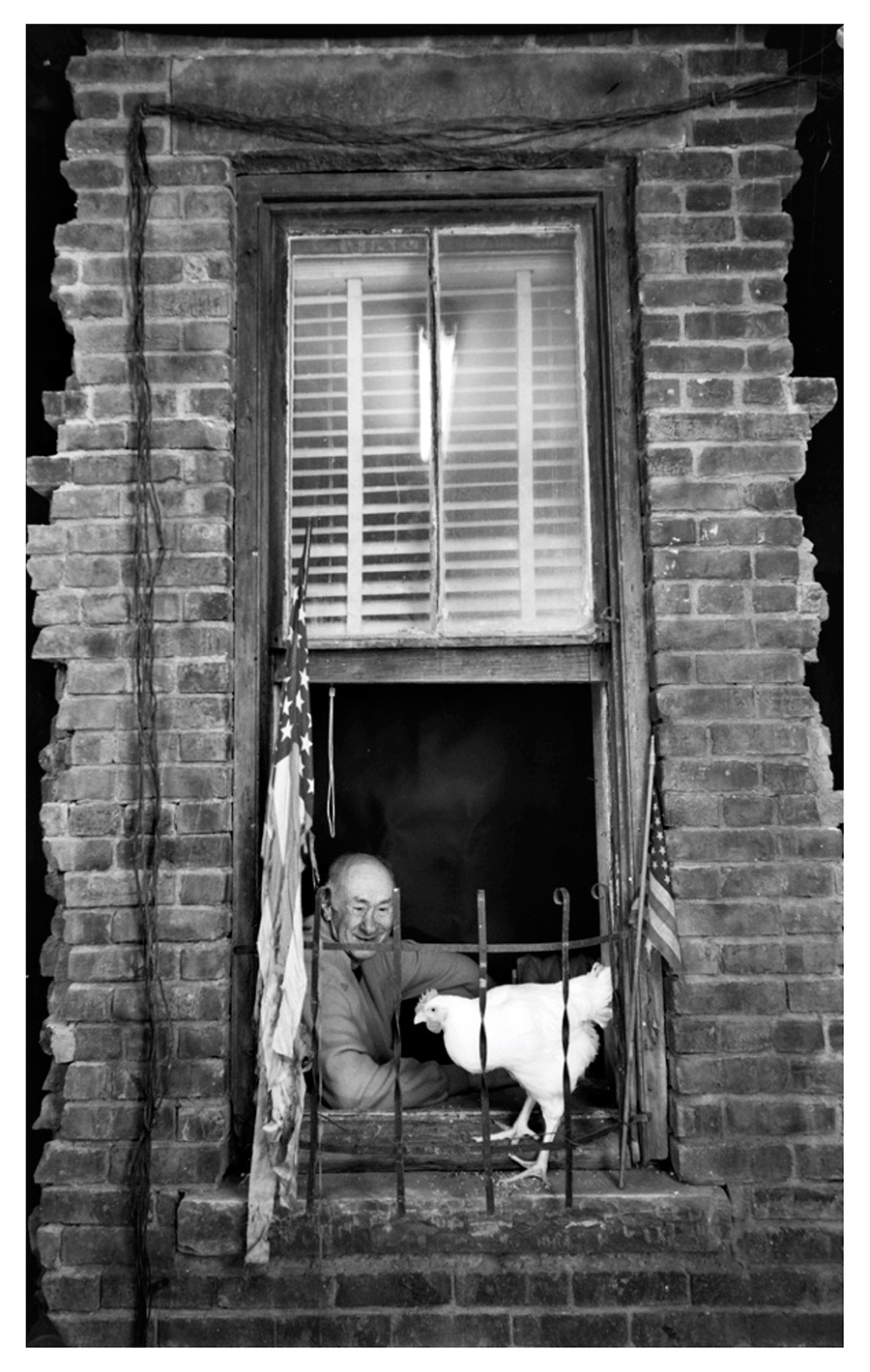

Stalking parades, street fairs, and feast days, Masao Gozu photographed the diverse residents of New York’s immigrant neighborhoods peering out apartment window frames. In almost all of the photographs of windows, the subjects are gazing at some action outside the frame of the window, either on the street below or up in the sky above. This series entitled 33 Windows references the number 33 which in Buddhism is a sacred number representing infinity.

Gozu’s Window Series captures the “zeitgeist” of New York in the 70s and 80s with as much aesthetic appeal as some of the storied photographs of the city such as those by Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, and Alfred Stieglitz. There is, however, something distinct and unique in Gozu’s artistic vision. Through the repetition of his formal composition in which the window frame is always centered in the photograph, Mazao Gozu’s pictures represent less of a documentation of everyday life, and more of an investigation into time and form.

This conceptual nod to the architecture of the window is reminiscent of the work of Bernd and Hilda Becher whose pictures of industrial structures from the same time period evade the categorization of traditional landscape photography. Their “tableau-like arrangements …always created and conceptualized according to the same parameters, inscribe themselves in the presentation space.” The Bechers label their work as Anonyme Skulpturen or Anonymous Sculptures.”¹

In his other photographic series 264, and Harry’s Bar, the practice and discipline of taking repetitive photographs over the course of years from the same position again and again hints that photography was a tool in part of a much larger conceptual practice. In Harry’s Bar, Gozu hunted the precise moment when a bar patron appeared in the exact position in lower left windowpane of a bar at 98 Bowery. To produce a series of 20 photographs, Gozu spent five years rigorously tracking and hunting the absolute image.

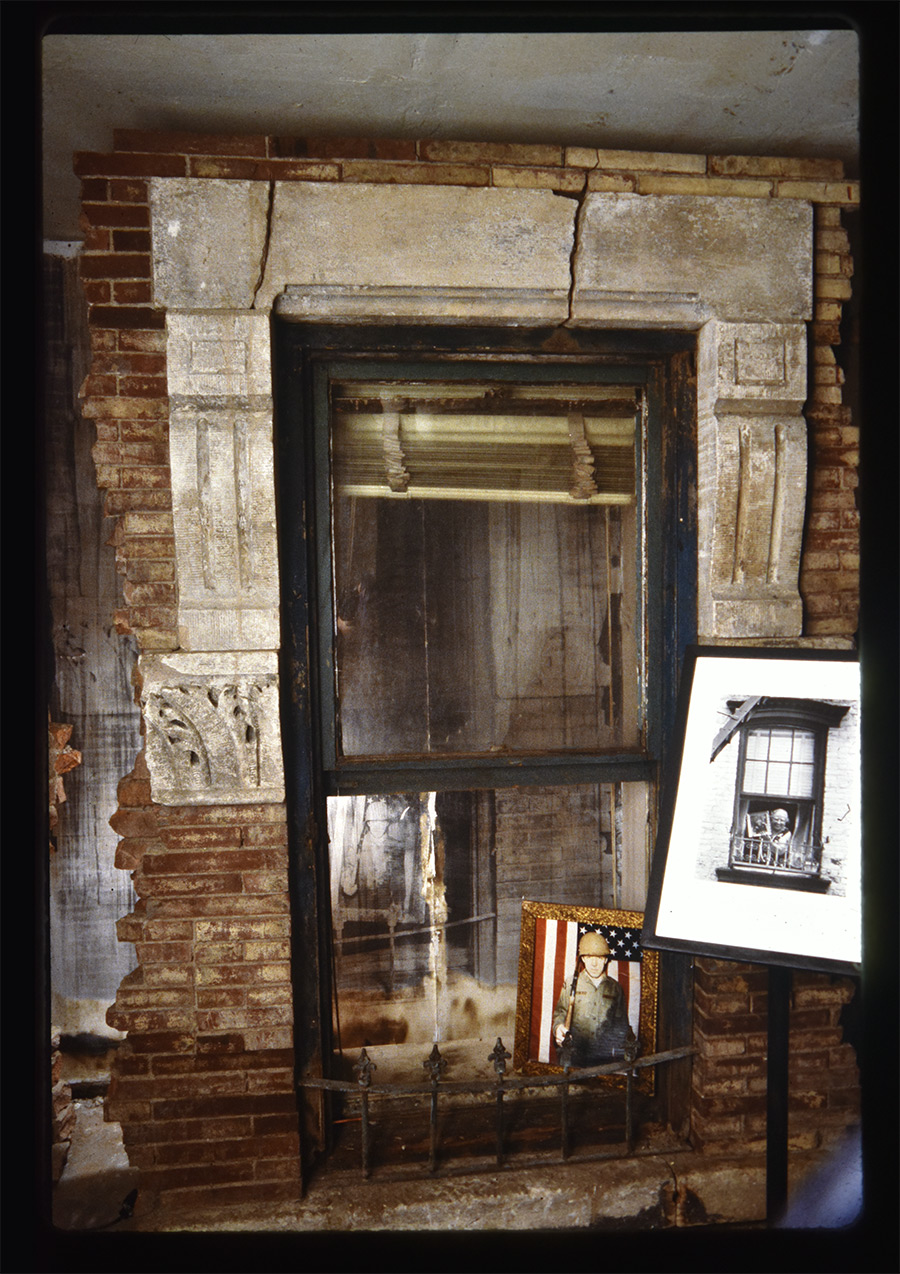

I asked Gozu how he transitioned from taking pictures of buildings to making sculptures with buildings. He answered that, “It started with Harry’s Bar.” Masao writes, “When it closed, I saw a sign that said ‘Everything for Sale’ and had the idea of buying the entire window and exhibiting it at a photo exhibition with photo. I tried to negotiate with the bar, but it didn’t work out.”

Masao continues, “Then, around 1983, I came across a destroyed building near Wall Street area and tore off the bricks and window frames from the surface, carried them to my apartment, and rebuilt them. It was an ordinary apartment, so the living room floor sank, so I quickly secured space in the basement of a nearby East village apartment and started assembling the windows.”

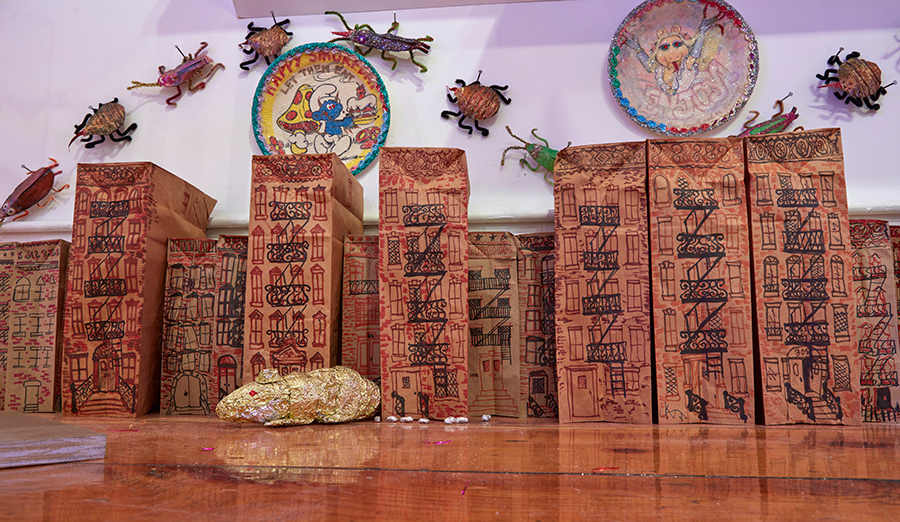

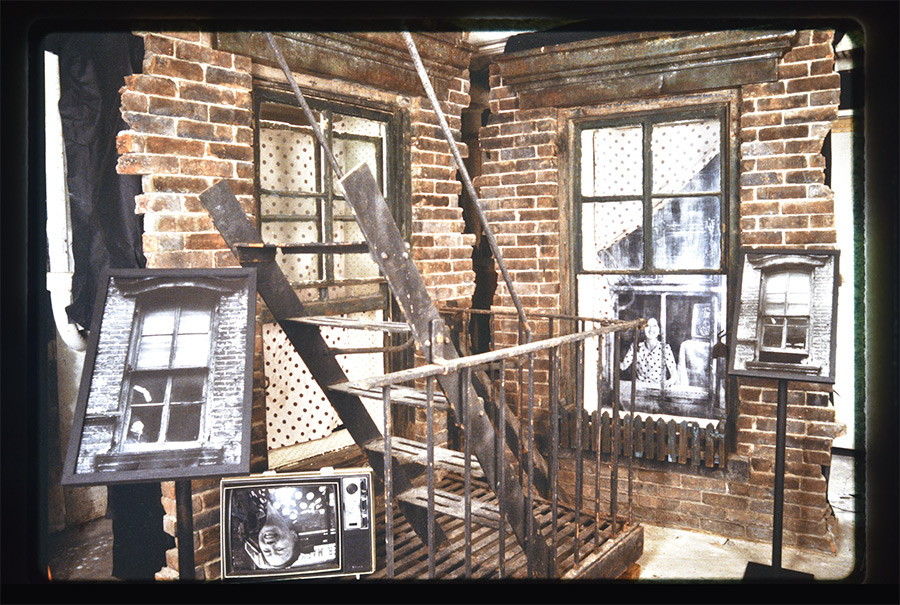

In his quest to capture the fleeting images he chased, Masao methodically marked, numbered, and then removed the bricks, glass panes, and mortar from the window frames of abandoned buildings in the East Village, reconstructing them in his studio. He enlisted his neighbors as models and dressed the windows with taxidermy, curtains and flowers. By staging the photos, he could have more control over the subject and composition, yet it’s clear that, in the process of making these pictures, Gozu’s persistence and meticulous rebuilding allude to the fact that his use of photography belied his affinity for sculpture.

It’s difficult to imagine anyone attempting to steal entire sections of buildings in today’s New York, but the East Village was lawless during the 1970s through the early 1990s. Heroin addiction and then crack were endemic to the East Village. In October of 1975, the city was hours away from bankruptcy as mayor Abraham Beame announced to the press, “I have been advised by the Comptoller that the City of New York has insufficient cash on hand to meet its debt obligation due today… Now we must take immediate action to protect essential life support systems of our city to preserve the well-being of all our citizens.”²

Robbery and assaults were reported at all-time highs, and as middle-class families abandoned the city so did landlords abandon and neglect buildings. Squatting was rampant up until the late 1980s.

Artists like Gozu were taking advantage of the city’s demise. Dismantling buildings is reminiscent of the work of Gordon Matta-Clark who staged a series of actions in the early 1970s in abandoned buildings in the Bronx and in piers along Manhattan’s waterfront which exist today only in photographs. Masao says he was not aware of Gordon Matta-Clark at the time.

During this period photography expanded sculptural practice, “It permitted the sculptors of the 1960s and 1970s to emerge from their studios and the white cubes of galleries and museums, and to make remote desert zones, downtrodden urban districts, indeed the entire social environment, the venues of their spatial/sculptural interventions. The expansion of the sculptural field as we know it from Earth Art and Street Art was based essentially on the authenticating, indexical character of the photographic image.” ³

Masao Gozu staged 8-10 of these photographs. They were laborious, physically strenuous, and time-consuming. These actions were also physically dangerous. One night, he recounted, he was carrying pieces of a building and a tripod back to his studio when he was surrounded by police who had been tipped off that someone matching Gozu’s description was carrying a shotgun. Later, in an abandoned building in the Bronx, two men threatened to shoot him.

Reconstructing the windows as set pieces planted a sculptural seed. As he constructed these windows, Gozu realized that the solemnity of an empty window frame without the human figure was the embodiment of the ephemeral state that he had long sought to capture through his pictures. By removing the figure from the window, Gozu, as he recently described, now saw the empty frames as mirrors, “empty windows are now the stage that can reflect me.”

During the installation of his show Time Frame, I marveled as he hoisted section upon section from his perch atop metal scaffolding. The determination, rigor, and discipline that Gozu demonstrates in his work is inspirational. He will spend five years taking photographs from the same spot, and thousands of hours assembling tons of rock to create a sculpture which is a monument to the fragility of time, a concept that he calls “Nagare” or stream, in which he sees himself as an ephemeral moment in the span of eons.

As I write about Masao, I can conjure a 3 am Bowery moment in the 1980s when, with a cart full of bricks, Masao passes Keith Haring painting his first large-scale mural on the corner of Bowery and Houston.

___________________________________________

¹ Bogomir Ecker, Raimund Kummer, Friedemann, Malsch, Herbert Molderings(ed.), Lens/ Based Scuplture, The Transformation of Sculture Through Photography, exhibition catalog, Academie der Kunst , Berlin, and Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein, Vaduz, 2014, 86.

² Jeff Nussbaum, The Night New York Saved Itself From Bankrupcy, The New Yorker, October 16, 2015.

³ Roxana Marcoci(ed.) The Original Copy. Photography of Scultpure, 1839 to Today, With essays by Roxana Marcoci, Geoffrey Batchen and Tobia Bezzola, exhibition catalog, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010, 154.

About the Writer:

Ted Riederer is a multidisciplinary artist and curator whose practice merges punk ethos with poetic interventions. A former band member and the Founding Artistic Director of Howl! Happening: An Arturo Vega Project in New York’s East Village, Riederer has exhibited widely, from PS1 and the Liverpool Biennial to galleries in Berlin, Lisbon, and Bangladesh. His international project Never Records blends performance, vinyl, and community engagement.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY