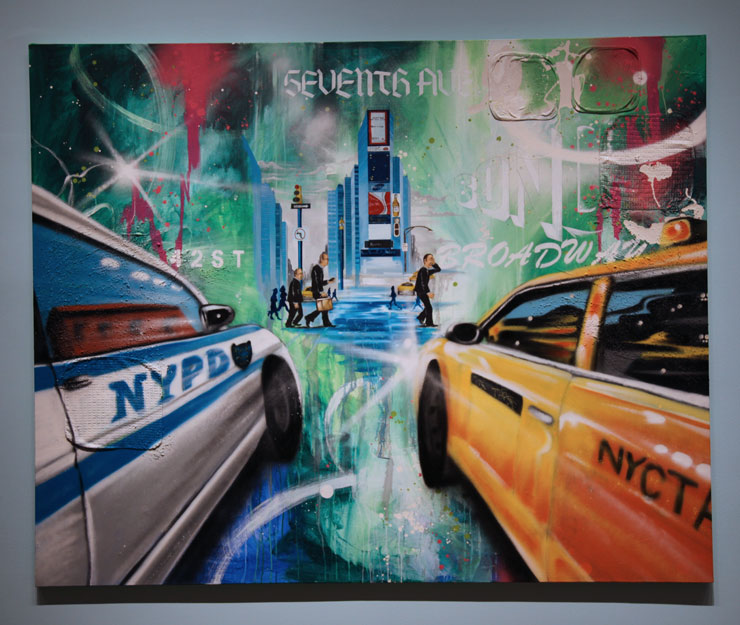

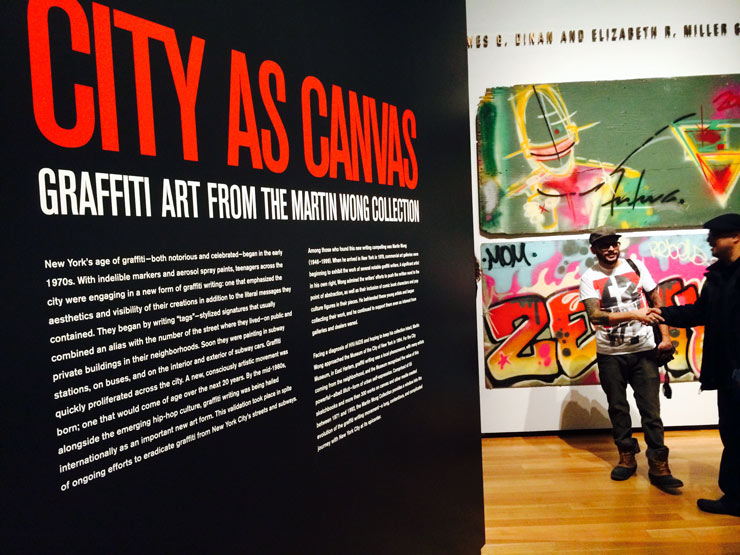

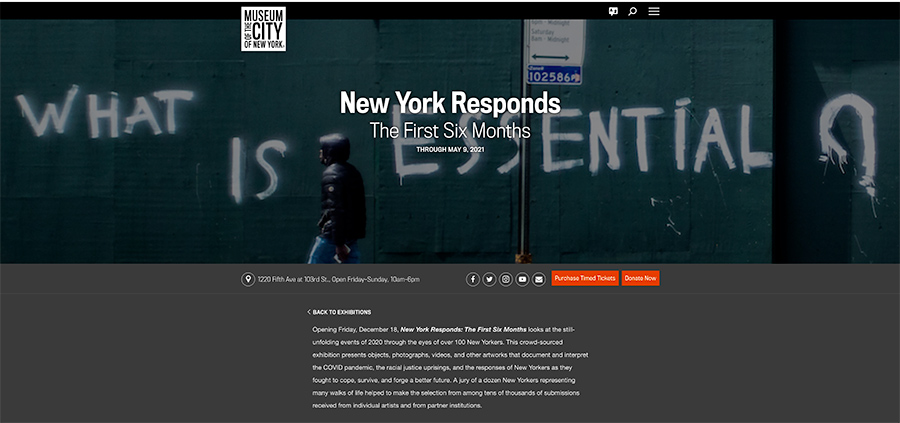

Last night the graffiti and early Street Art history from New York’s 1970s and 80s was celebrated by the City of New York – at least in its museum. Criminals and outlaws then, art stars and legends today, many of the aerosol actors and their documentarians were on display and discussed over white wine under warm, forgiving, indirect lighting.

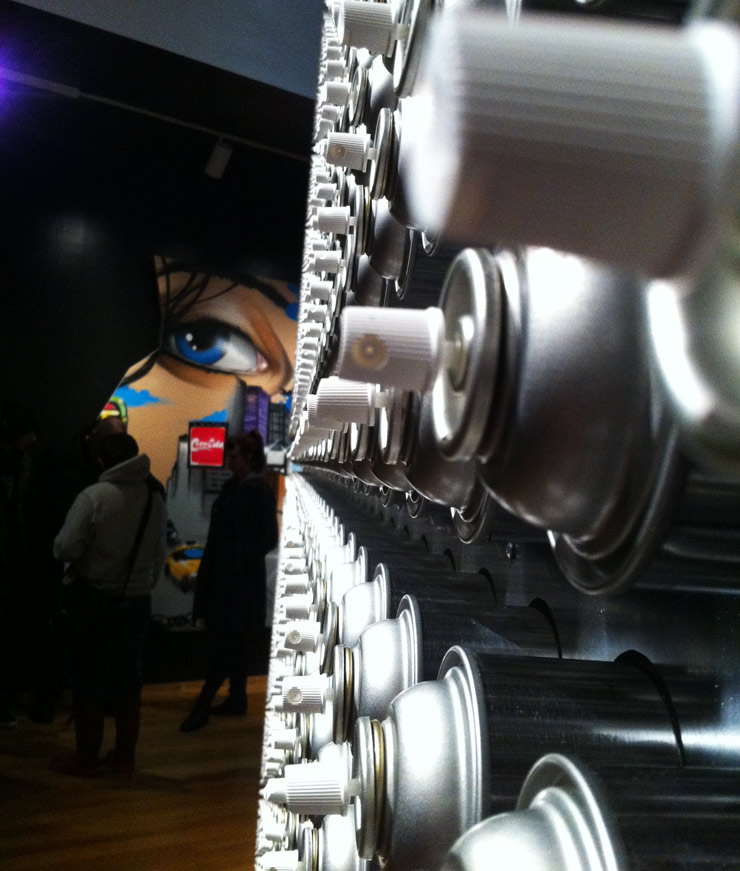

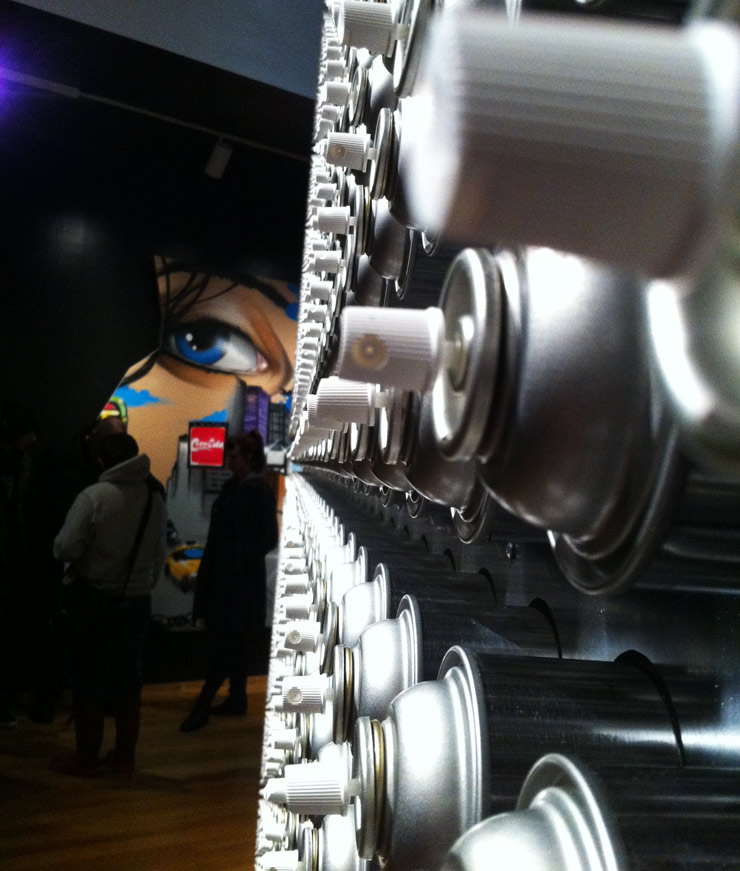

DAZE in the background sliced by a wall of cans at the opening of “The City As Canvas” (photo via iPhone © Jaime Rojo)

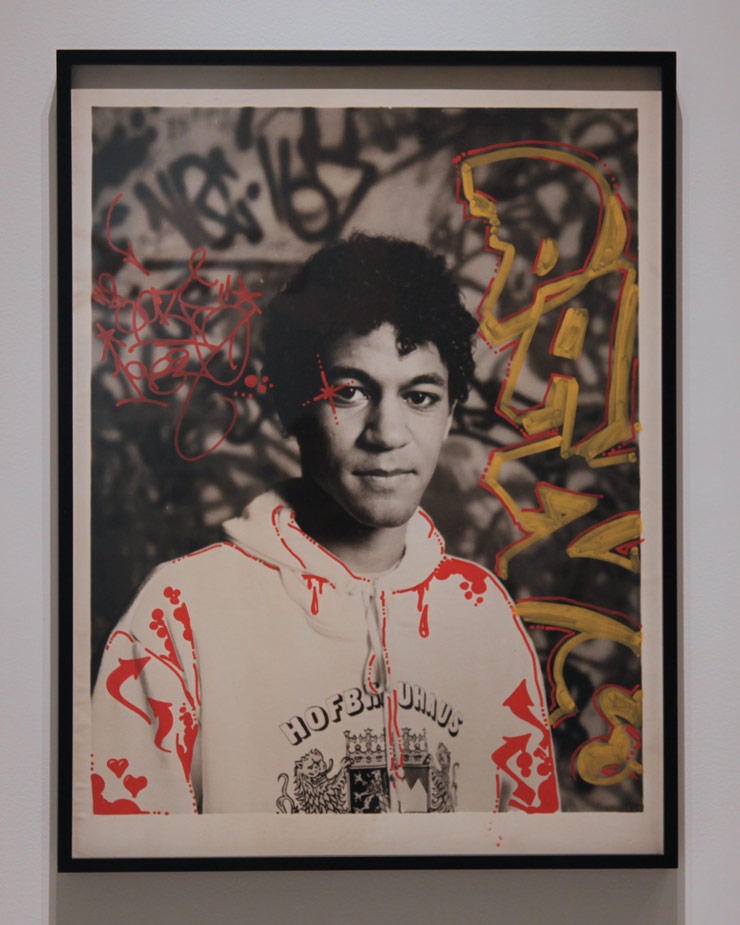

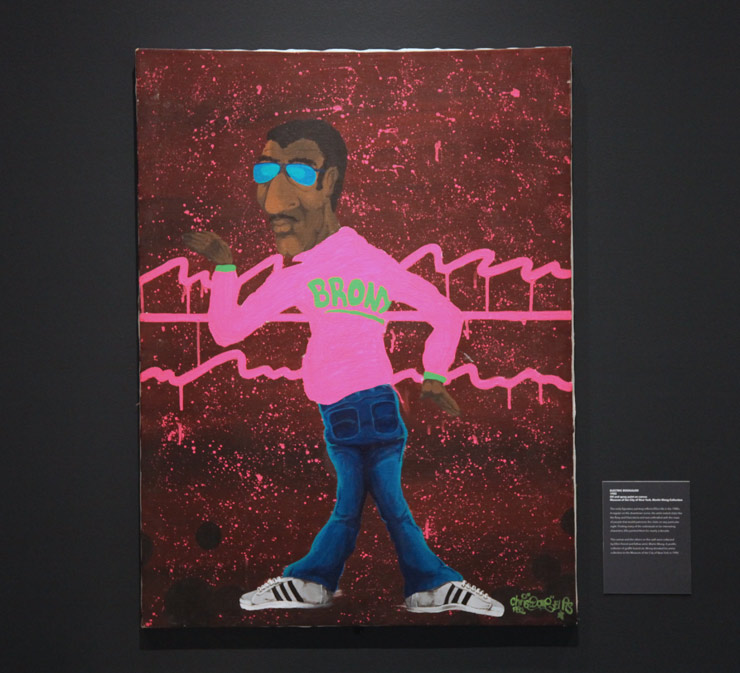

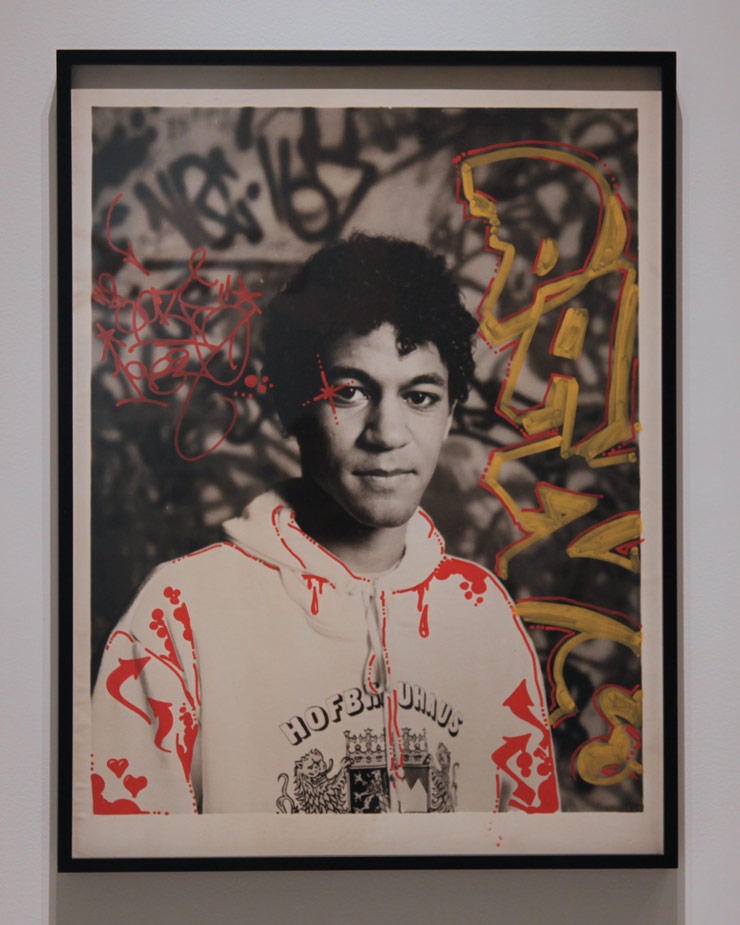

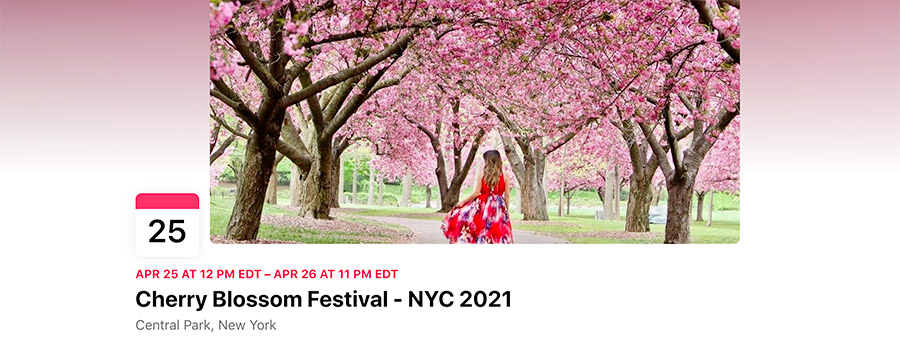

“City as Canvas: New York City Graffiti From the Martin Wong Collection” is an exhibition as well as a book released last fall written by Carlo McCormick and Sean Corcoran, with contributions by Lee Quinones, Sacha Jenkins and Christopher Daze Ellis, and all the aforementioned were in attendance. Also spotted were artists, photographers, curators, writers (both kinds), art dealers, historians, family, friends, peers and loyal fans – naturally most fell into a few of these categories at the same time.

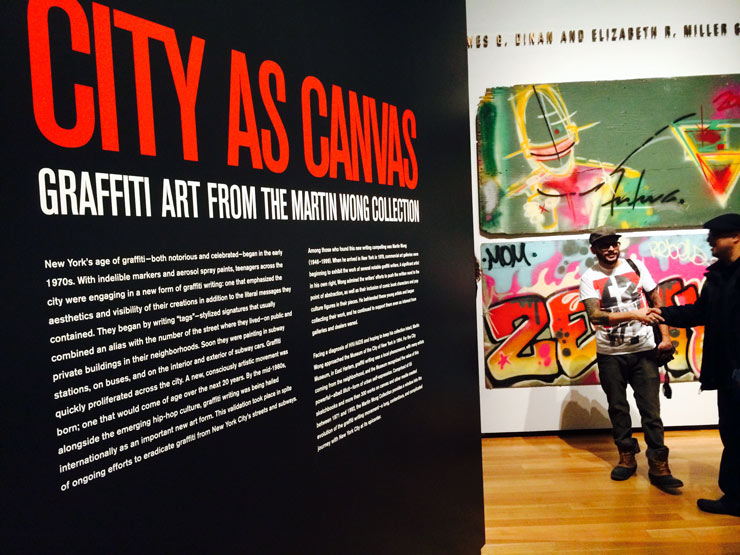

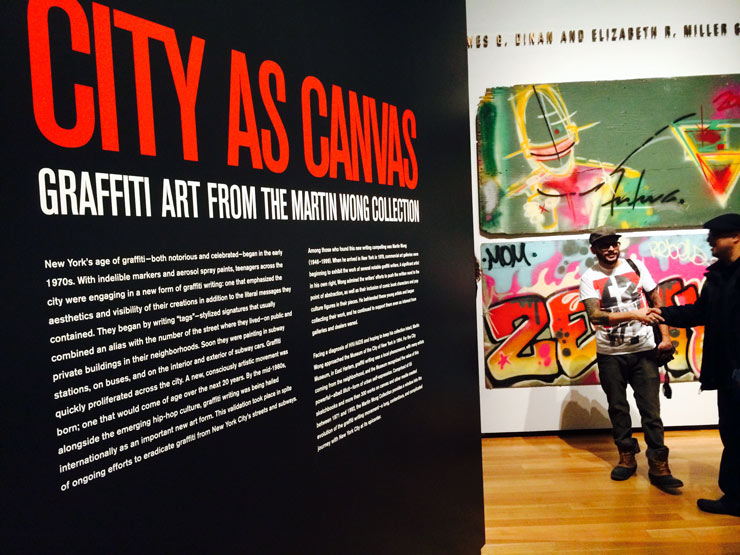

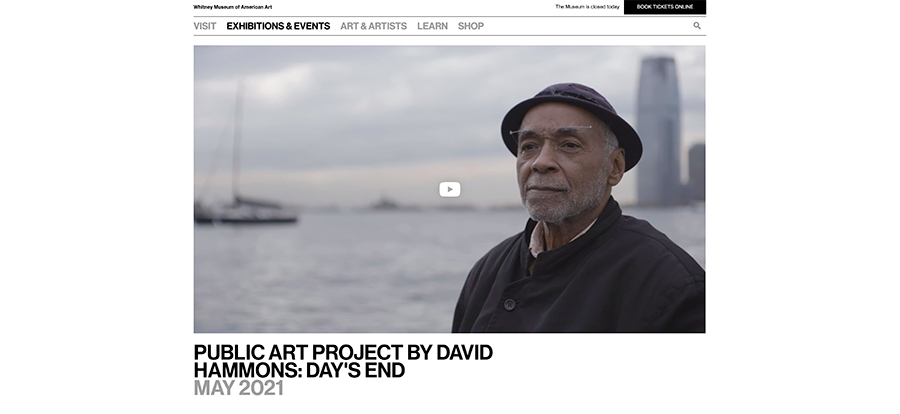

“The City As Canvas” exhibition at Museum of the City of New York welcome text with pieces by Futura 2000 and Zephyr to the right. (photo via iPhone © Steven P. Harrington)

“City as Canvas” is possible thanks to the foresight, eye, and wallet of collector Martin Wong, an openly gay Chinese-American artist transplanted to New York from San Francisco, which is remarkable not only because of the rampant homophobia and near hysterical AIDS phobia at the time he was collecting but because the graffiti / Street Art scene even today throws the term “fag” around pretty easily. A trained ceramacist and painter whose professional work has gained in recognition since his death of AIDS related complications in 1999, Wong is said to have met and befriended a great number of New York graffiti artists like Lady Pink, LEE, DAZE and Futura 2000, who were picking up art supplies where he worked at the Pearl Paint store – a four story holy place on Canal Street that thrived at that time.

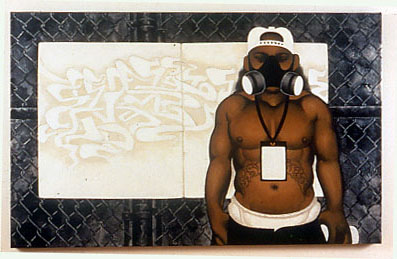

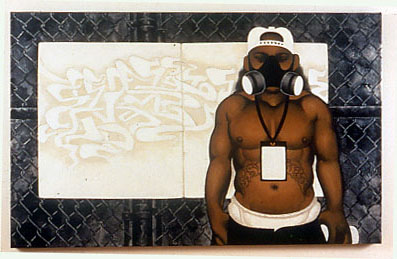

The show contains black books full of tags and drawings as well as canvasses and mixed media Wong purchased, commissioned, and painted, including a portrait of graffiti artist Sharp wearing a respirator and standing before a canvas he’s working on entitled Sharp Paints a Picture (1997-98).

The show contains black books full of tags and drawings as well as canvasses and mixed media Wong purchased, commissioned, and painted, including a portrait of graffiti artist Sharp wearing a respirator and standing before a canvas he’s working on entitled Sharp Paints a Picture (1997-98).

The mood at the museum was celebratory as guests looked at the 140+ works from Wong’s collection; a cross between an art opening and a graffiti trade show, with enthusiastic peers and fans waiting patiently to speak with, pose for pictures with, and gain autographs or tags in their black books from artists in attendance. The only officers that could be seen were holding back the line of guests to make sure there was no overcrowding of the exhibit.

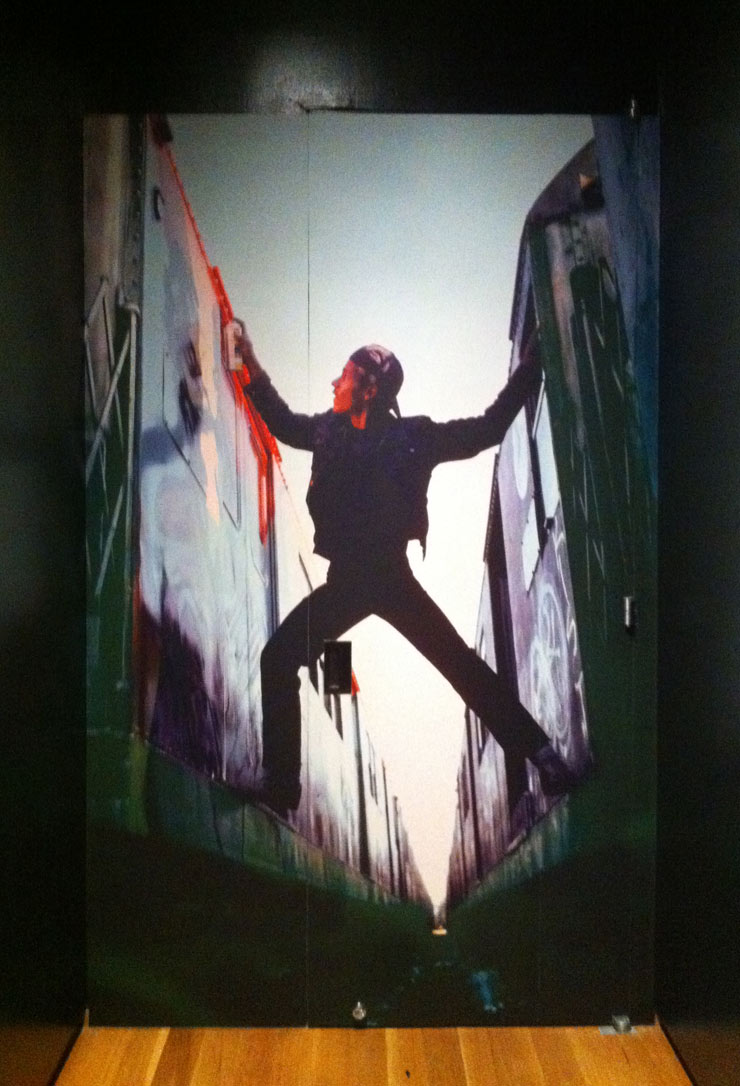

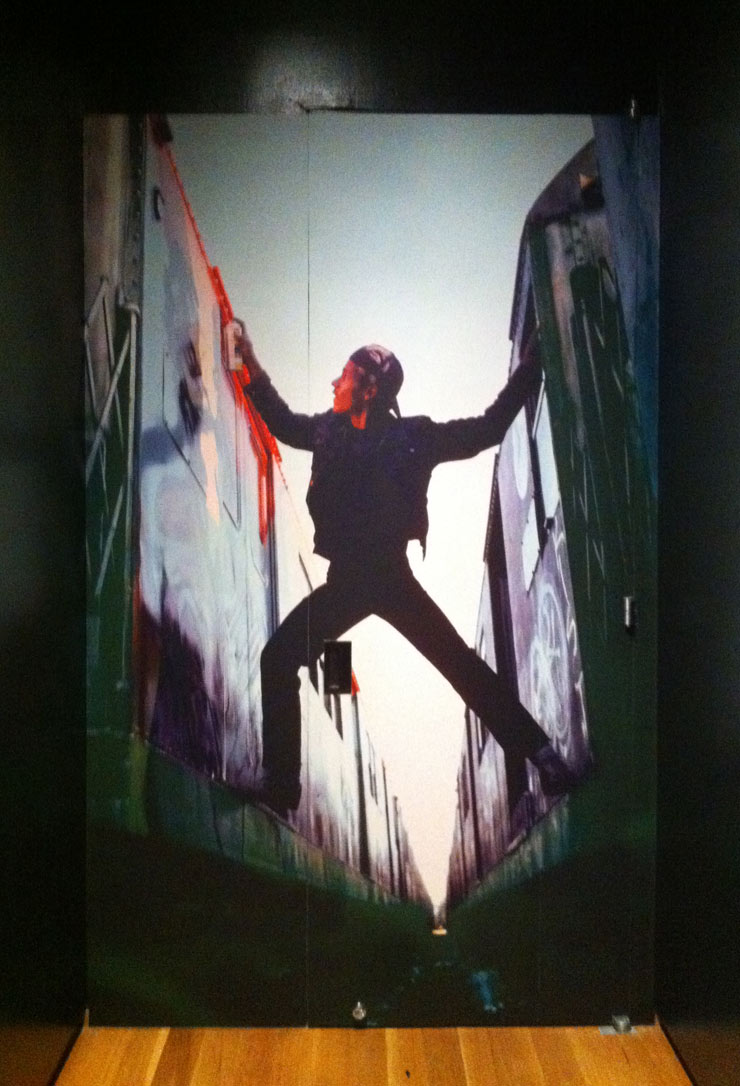

The famous Martha Cooper photograph of Dondi in action in the train yards. “The City As Canvas” exhibition at Museum of the City of New York. (photo via iPhone © Jaime Rojo)

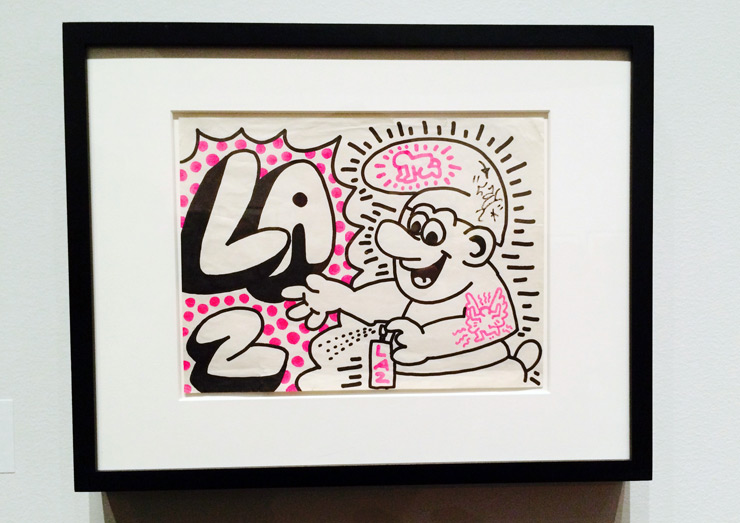

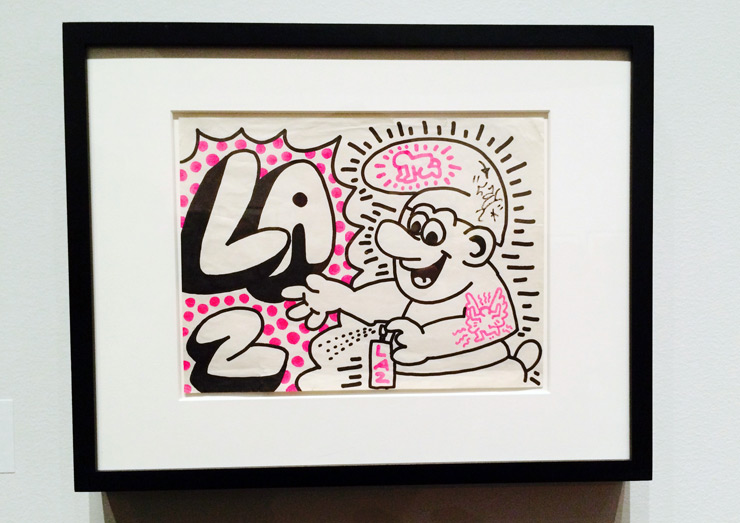

A Keith Haring and LA2 collaboration at “The City As Canvas” exhibition at Museum of the City of New York. (photo via iPhone © Steven P. Harrington)

Artist LA2 with Ramona “The City As Canvas” (photo via iPhone © Jaime Rojo)

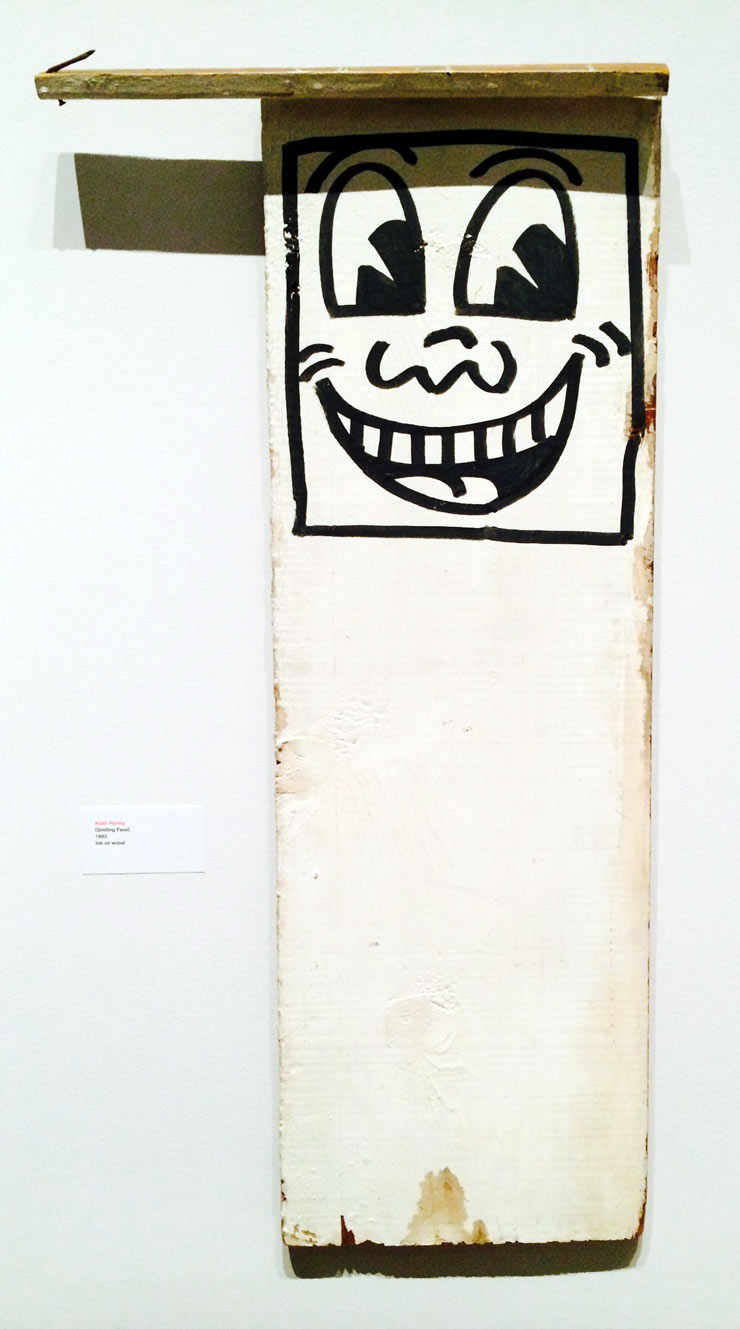

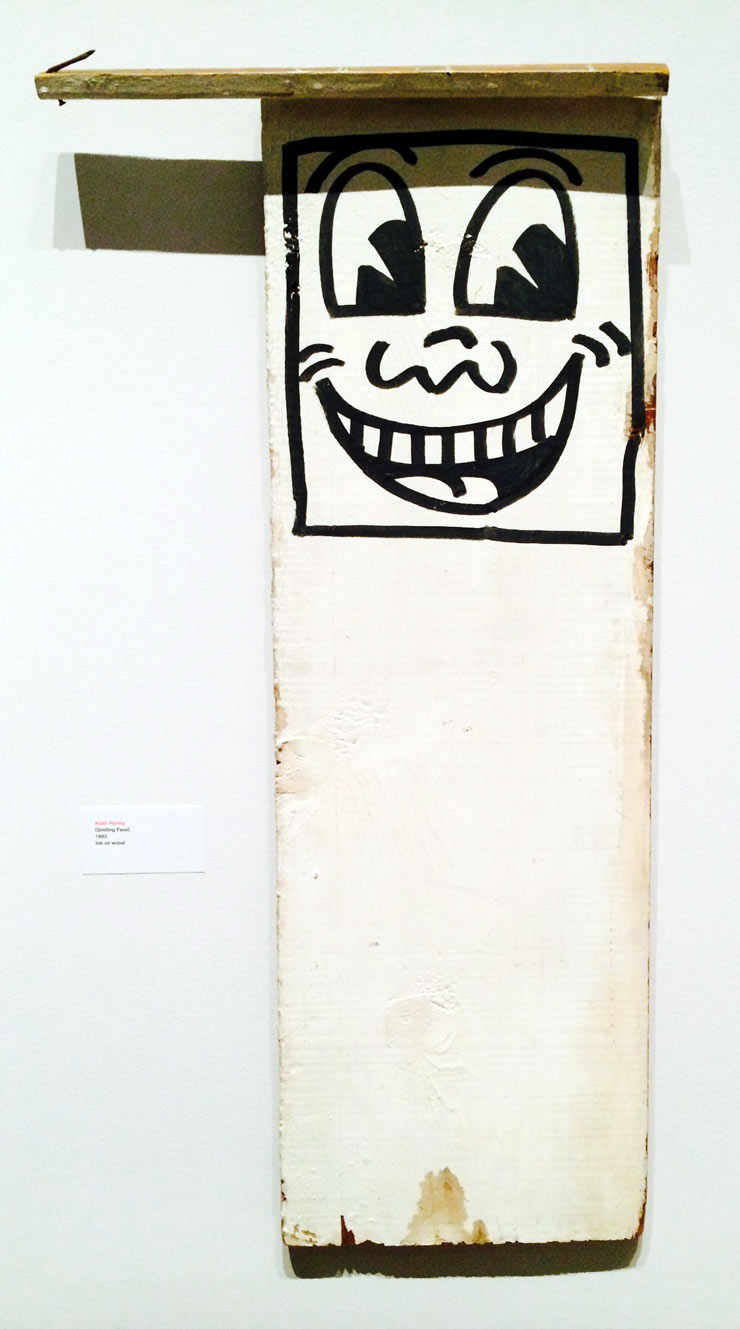

Keith Haring (Smiling Face) from 1982 at “The City As Canvas” exhibition at Museum of the City of New York. (photo via iPhone © Steven P. Harrington)

Lee Quiñones speaking with a never ending stream of fans before his canvas Howard the Duck, 1988, at “The City As Canvas” (photo via iPhone © Jaime Rojo)

Digital prints of images shot by photographer Henry Chalfant brought the trains alive. On top is an image of a train with Sharp/Delta 2 from 1981 and below is “Stop the Bomb” by LEE (Quiñones), 1979 at “The City As Canvas” exhibition at Museum of the City of New York. (photo via iPhone © Steven P. Harrington)

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA

Please note: All content including images and text are © BrooklynStreetArt.com, unless otherwise noted. We like sharing BSA content for non-commercial purposes as long as you credit the photographer(s) and BSA, include a link to the original article URL and do not remove the photographer’s name from the .jpg file. Otherwise, please refrain from re-posting. Thanks!

<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA<<>>><><<>BSA<<>>><<<>><><BSA

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY