Steven P. Harrington

After Hours at the Museum of Graffiti

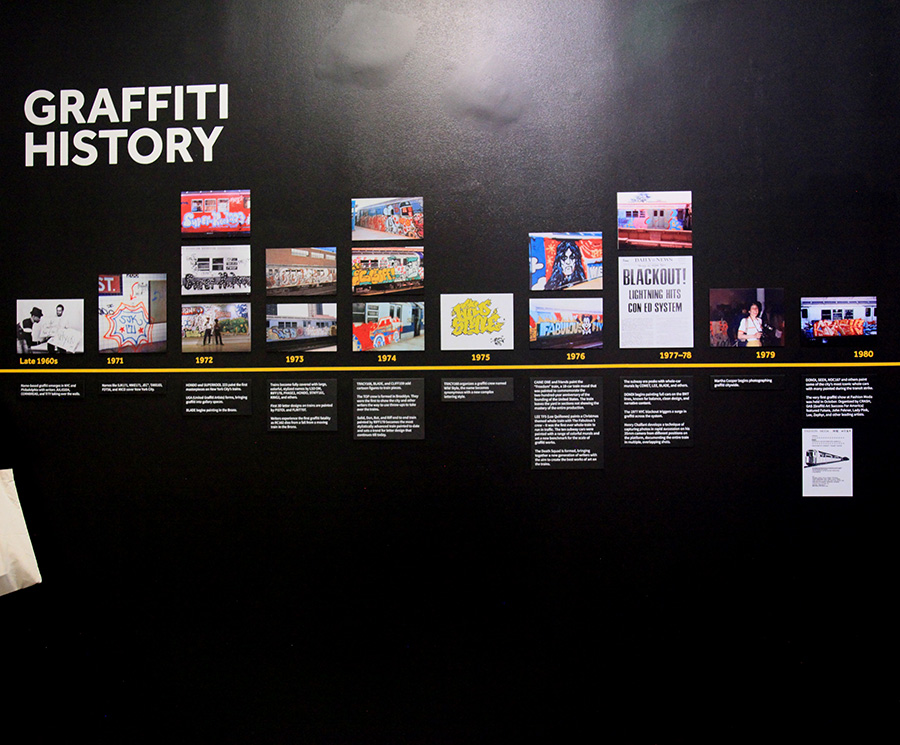

On a late-night private tour during the Art Basel week madness, with just two guests in tow, the Museum of Graffiti can feel less like a public institution and more like an unlocked archive after hours—quiet enough to hear details that usually get lost in daytime traffic: the cadence of a tag, the logic of a crew name, the way a single artifact can rearrange what you thought you “knew” about the early years.

Alan Ket, co-founder of the museum alongside Allison Freidin, has an advantage as a guide that goes beyond carrying the historian’s timeline in his head. He knows the people in that timeline. Together, Ket and Freidin have spent years building a place where those histories can be shown without being flattened into a slogan.

Three Arguments, One Program

The current program is structured like a three-part argument, each section reinforcing the next: the foundation of UGA-era legitimacy, the long arc of a writer who outlived the rules and the era that formed around graffiti, and a parallel street-writing tradition from Brazil that insists on its own terms. Around those anchors, interstitial context stations—about Subway Art, about a “Hall of Fame,” about what writing is when it’s more than a product—and those do real work in a short visit, especially when the museum is closed, and you’re not fighting a crowd.

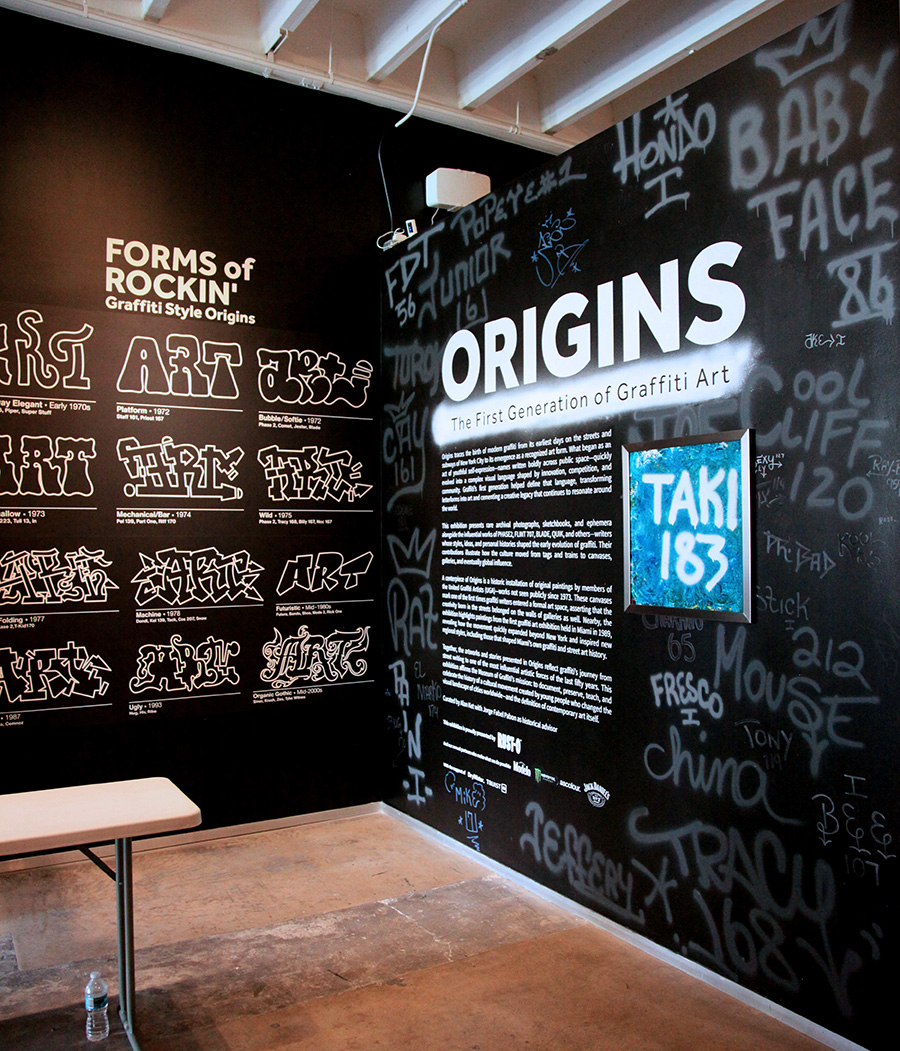

Origins: Writing Enters Public History

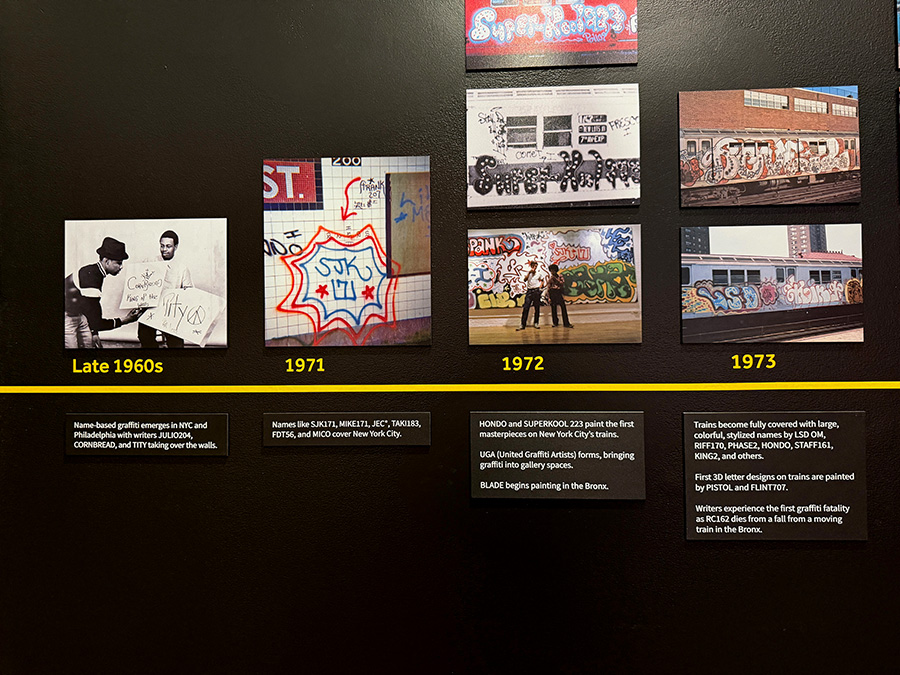

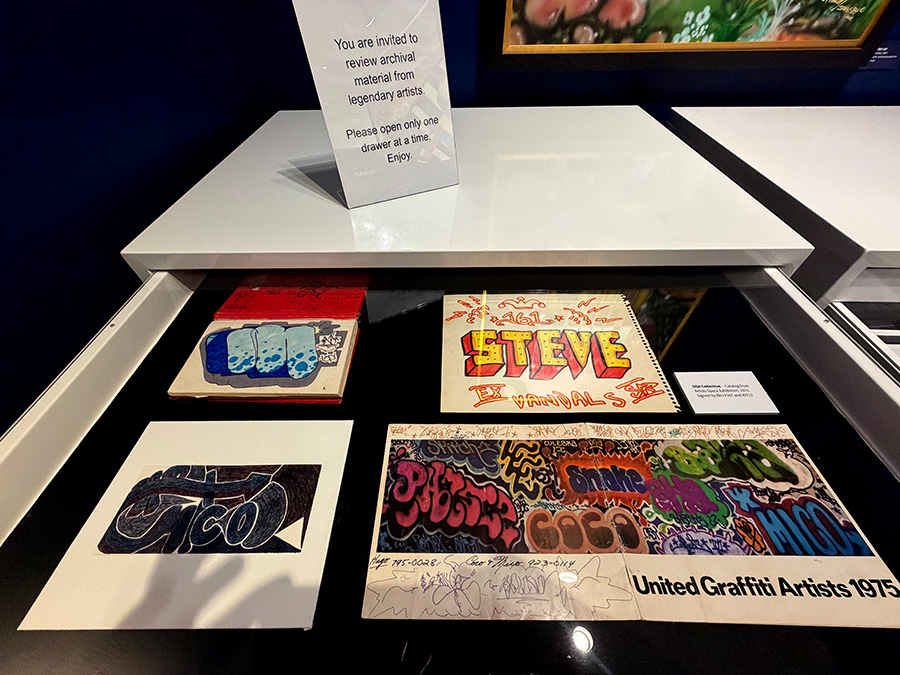

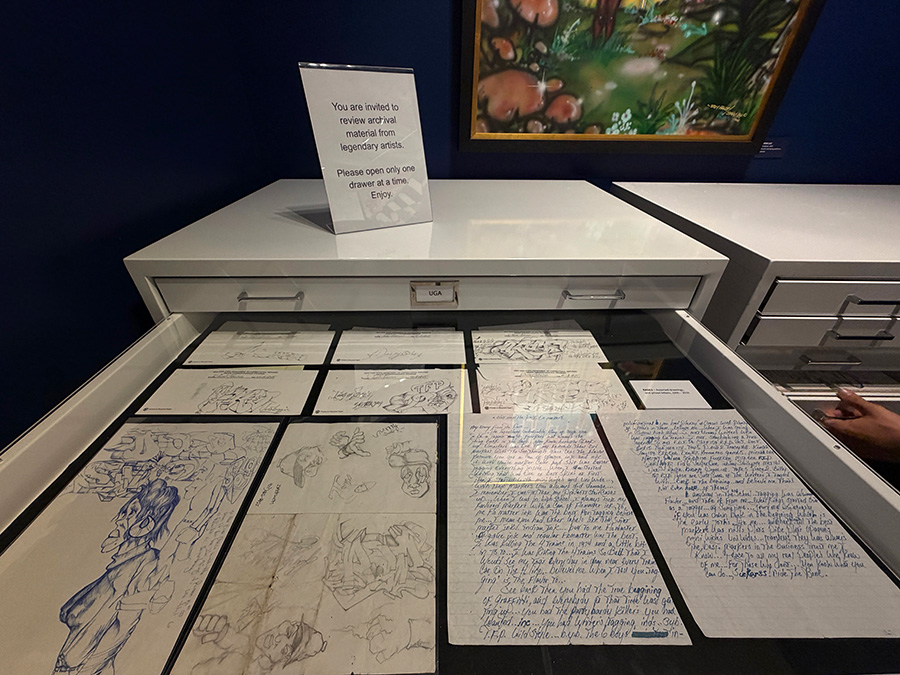

The Origins exhibit opens with a title that doesn’t hedge: “UNITED GRAFFITI ARTISTS (UGA), 1972–1975 — The First Organized Graffiti Collective.” The wall text frames the early 1970s not as a hazy prelude, but as a moment when New York’s walls and trains became “the visual language of a new generation writing its name into history.” The intent is clear: to meet those writers as authors, not as an anonymous “phenomenon.”

In a key early moment, a 22-year-old sociology student at City College of New York, Hugo Martinez, pulls together a group, a show, and a generation of young writers emerging from an expanding visual movement. Seeking out Puerto Rican and African American writers, Martinez traces an early chain of connection—through HENRY 161, he meets active Washington Heights figures including SNAKE 1, SJK 171, MIKE 171, STITCH 1, and COCO 144—and invites them into something new: a collective, publicly legible, with a name that could travel.

The Canvases Reappear

The exhibition pins down a crucial milestone: UGA’s first exhibition at City College in December 1972, anchored by a 10-by-40-foot collaborative mural that drew coverage in The New York Times. That context explains why the newly surfaced canvases land with such force today. They aren’t “early work” in the abstract; they are evidence of one of the first moments graffiti writers entered an art context without shedding the culture’s DNA.

Then Ket takes you to the proofs themselves—the ones that stop conversations. He describes the unveiling of the massive canvas as a reunion at the edge of disbelief:

“We opened yesterday—the first time anyone had seen the (mural by UGA) work publicly. Doze was here. Coco was here. Flint 707 was here. Mike 171 was here. Artists who were part of that original moment, or closely connected to it.”

And then the realization:

“A lot of people initially thought the paintings were replicas. Even people who knew the work. They couldn’t believe these were the original canvases.”

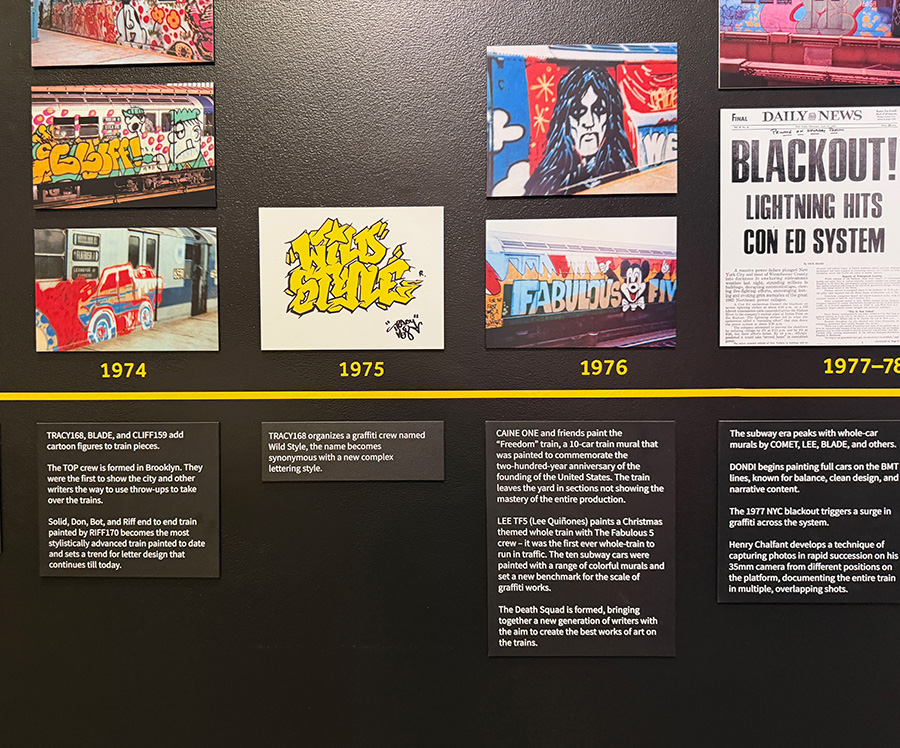

UGA’s short-lived run broke cultural barriers that still echo graffiti’s resistance by many institutions today, timid as they are to recognize this movement. The 1973 Deuce Coupe live backdrop performance with the Joffrey Ballet, UGA on the cover of New York magazine, and early exhibitions—including the group show at the Razor Gallery in SoHo—all pushed that door open. Like coming across a great piece on the street—there one day, gone the next—UGA’s tenure was brief, explosive, and foundational.

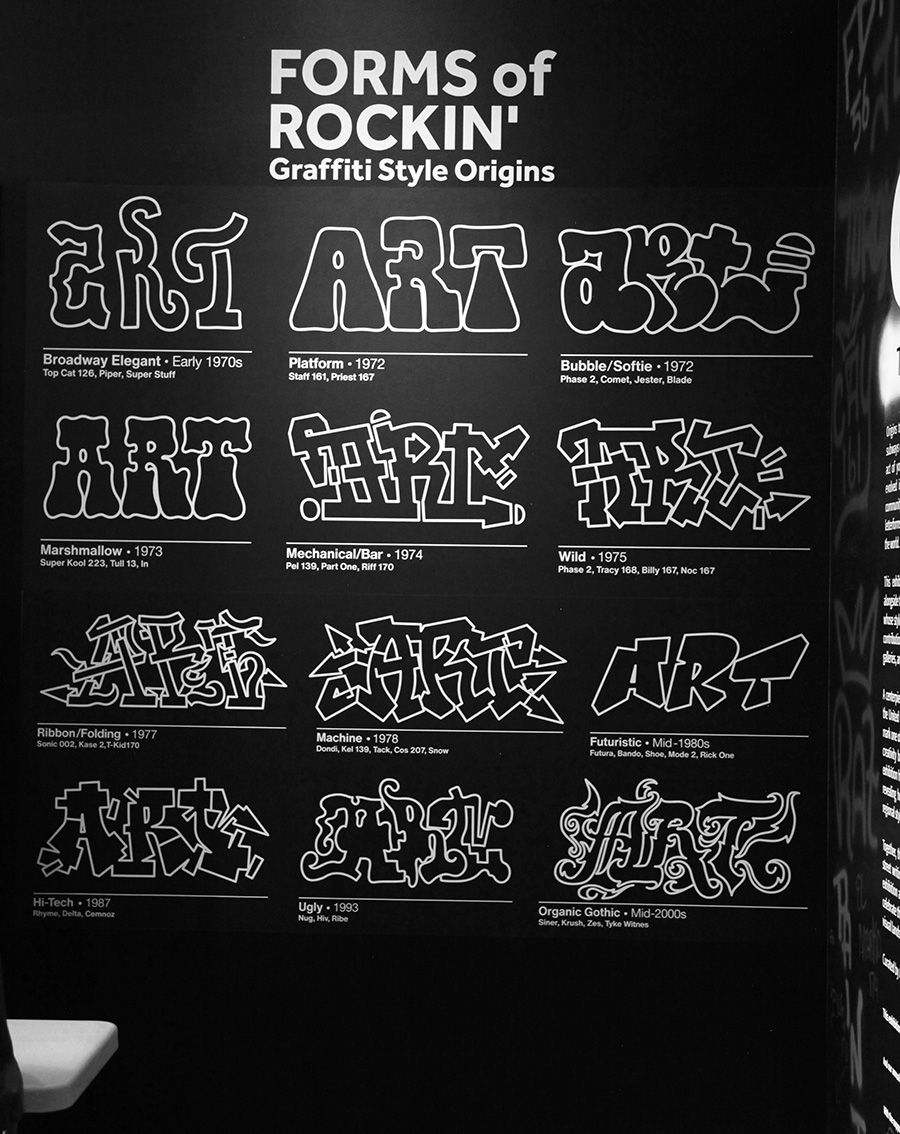

Context That Carries Weight

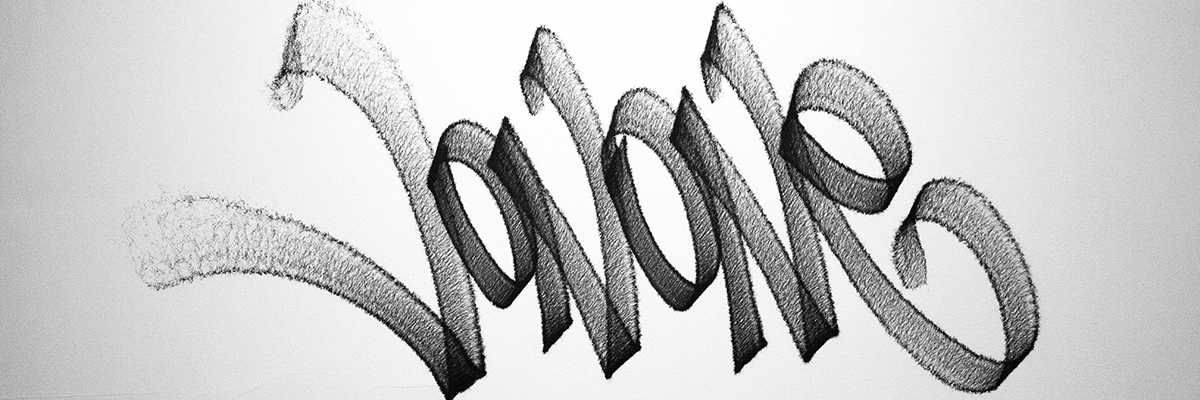

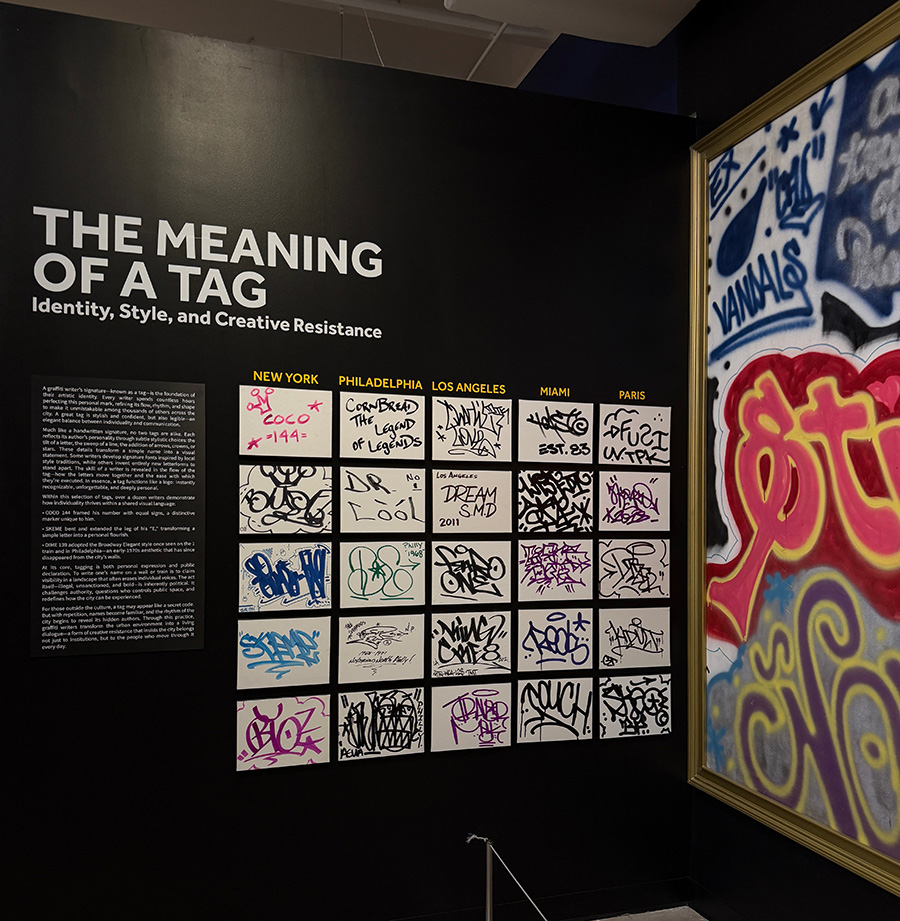

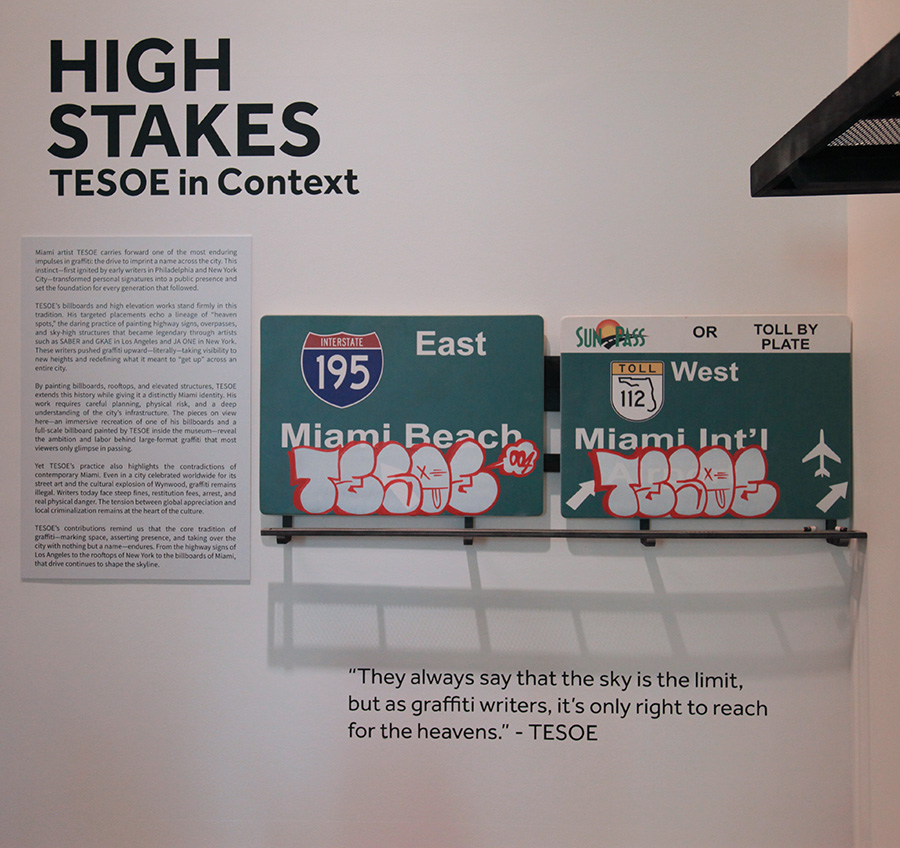

The museum’s educational nodes function as interstitial primers, uncovering codes and influences that might otherwise be missed. Between the larger narratives, local histories offer insight into Miami’s scene, here with a focus on Tesoe and his highway sign writing. The tag, forever individual and cryptic to the everyday observer, is decoded and compared across multiple cities, enabling a handstyle compare and contrast.

Elsewhere, a closer look at style points to a youthful desire for flash and image, shaped by the tensions of New York’s 1970s streets—gang violence, territorial pressure, and a driving need among artists to create, to mark presence, and to be seen.

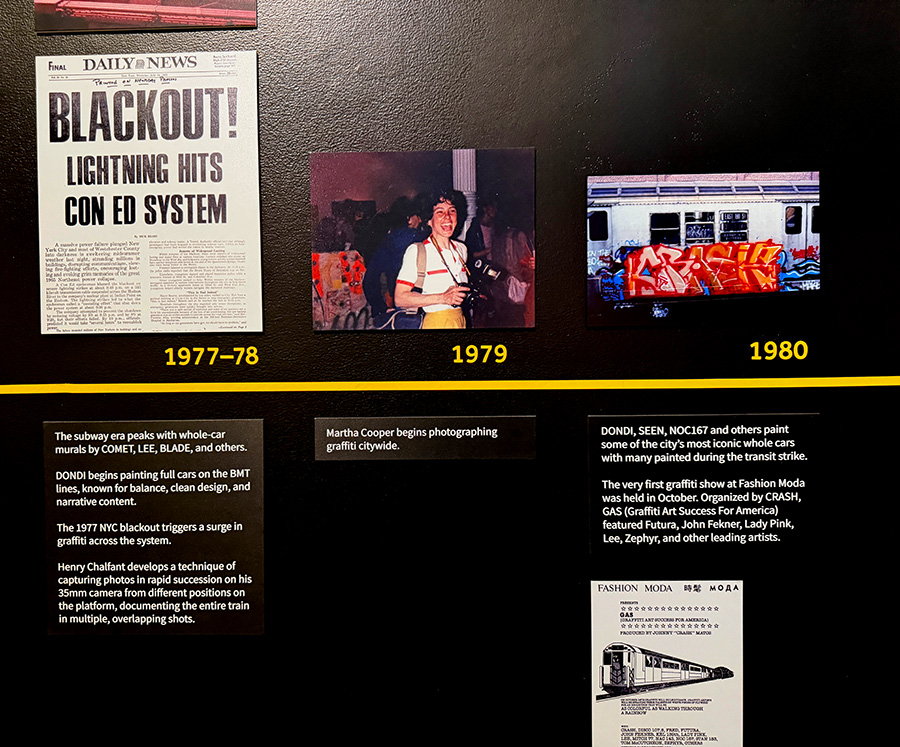

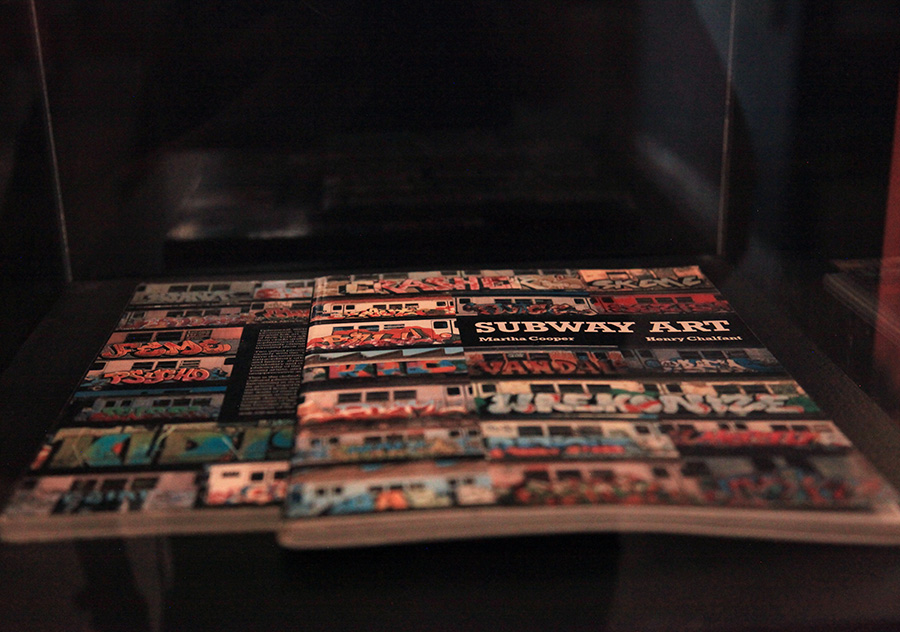

“SUBWAY ART: The Book That Changed Everything” is presented as the crack in the wall that allowed the rest of the world to look in. A quote from Daze underlines the point:

“I don’t think anyone could have anticipated the global impact that Subway Art has had on the culture. For many, it became the entry point to a worldwide phenomenon.”

“GRAFFITI HALL OF FAME — Strictly Kings and Better” shifts the lens from documentation to reputation—how writers judge writers. The inaugural class sets out clear benchmarks: CASE 2, DONDI, FUZZ ONE, IZ THE WIZ, and TRACY 168, with painted portraits by Beto Landsky. It points to a canon shaped internally, through practice, reputation, and peer recognition.

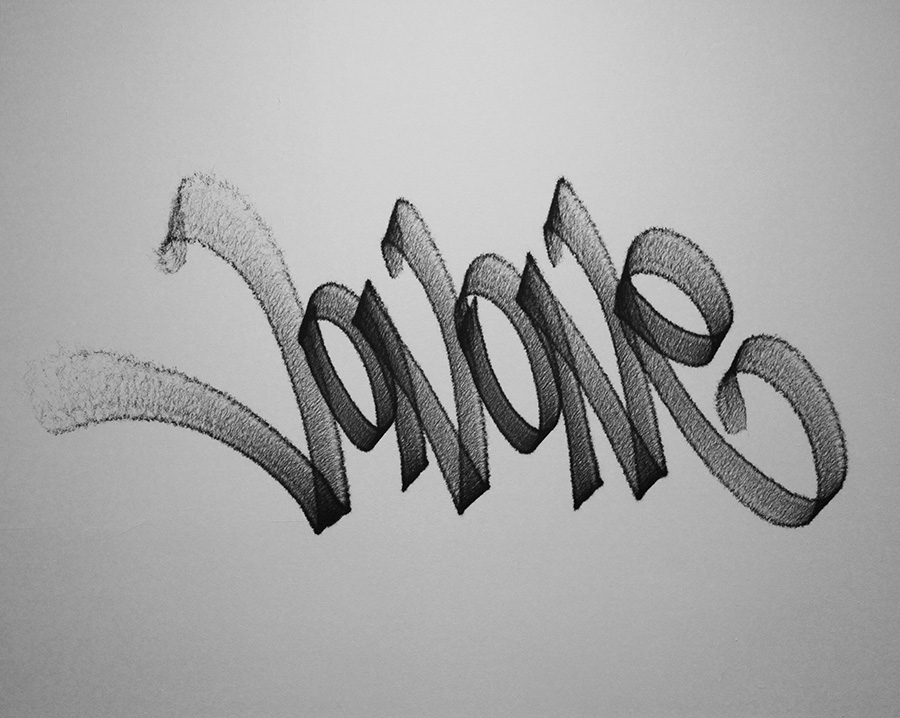

One of the most useful sentences in the building comes from PHASE 2, because it tells visitors what to value without preaching:

“Writing is centered on names, words, and letters… Writers agree without a doubt that there is an attitude and commitment within the soul that accompanies being a true writer… that one’s volume of work can in no way replace.”

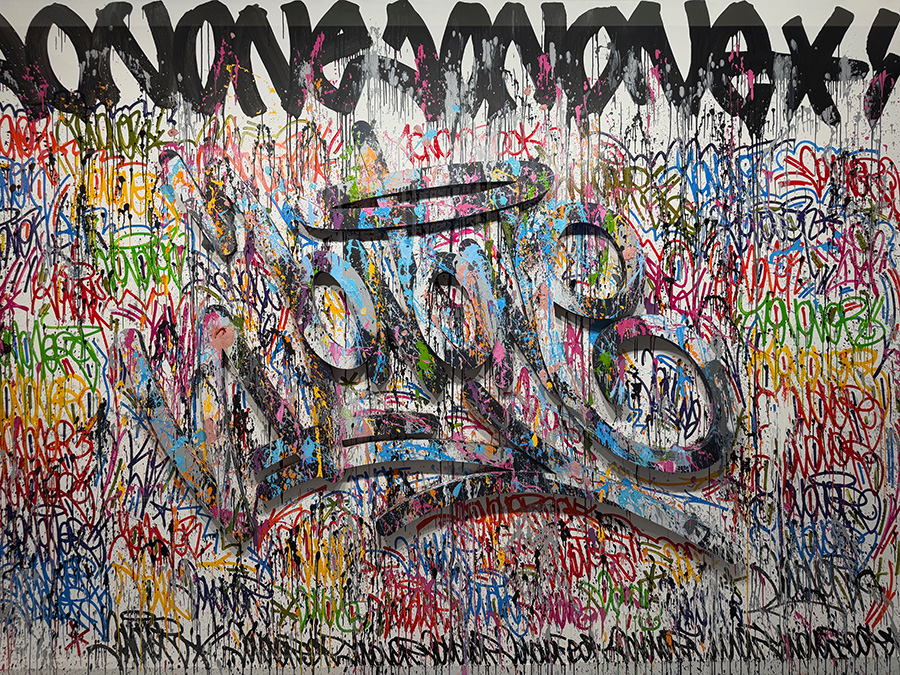

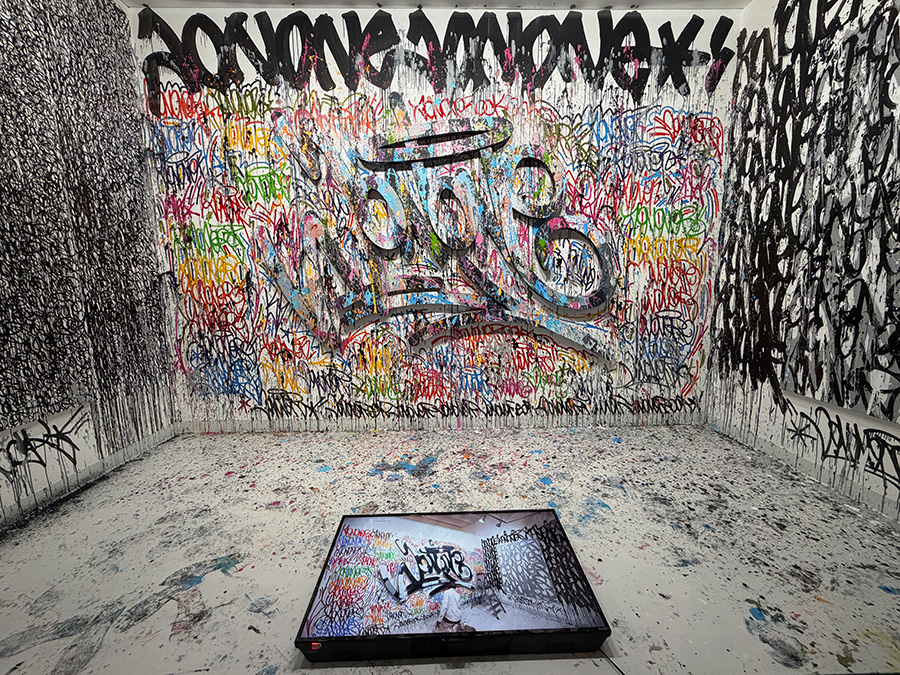

JonOne: A Life Laid Out in Public

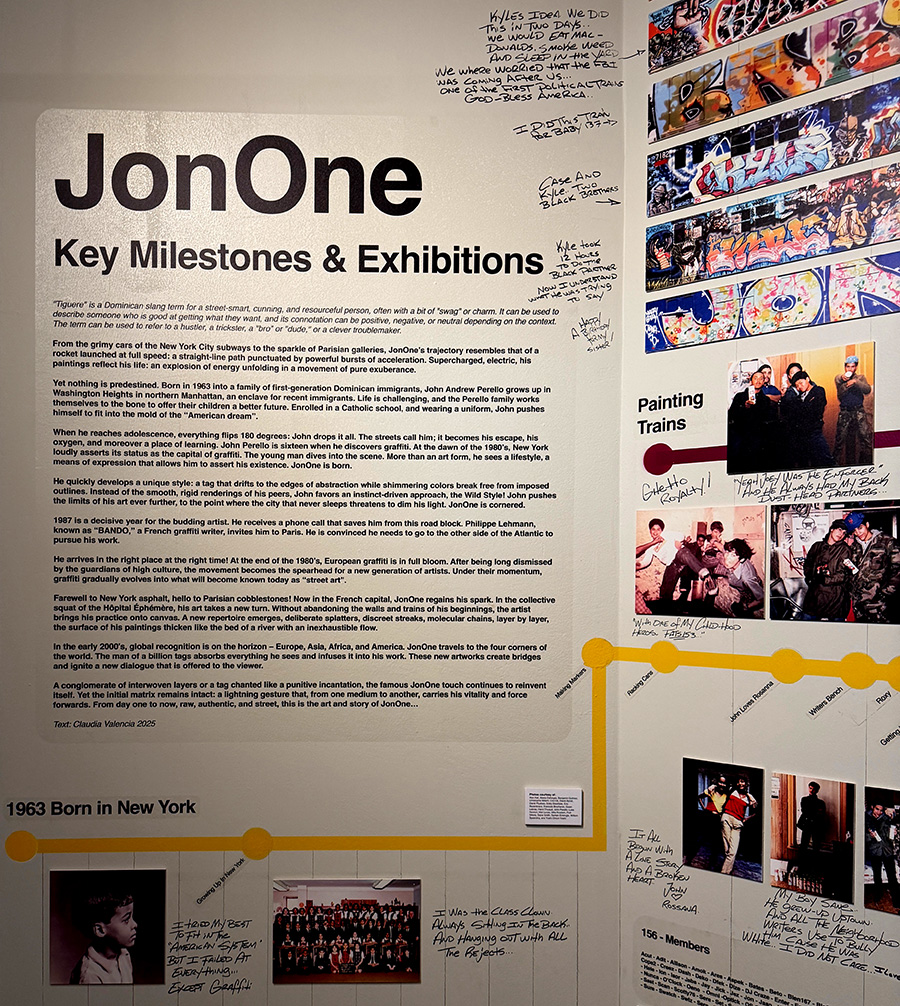

The JonOne featured section reads as a biography laid out in public, a sprawling timelines history that holds back little, crowding in detail and storytelling. “JonOne — Key Milestones & Exhibitions” is dense on purpose, with purpose. The wall text defines tiguere as Dominican slang for someone street-smart and resourceful, then charts the arc from Washington Heights adolescence into 1980s New York graffiti, where the city “asserts its status as the capital of graffiti.”

The timeline—supported by the artist’s own handwritten explanations—allows visitors to track the evolution without forcing a “from trains to galleries” redemption narrative, as if commercial success retroactively absolved the past. It doesn’t skip the way things actually played out: Catholic school discipline, immigrant family pressure, street education, and the reconfiguration of practice in Paris.

Ket’s words strike the right balance:

“I have been following Jon’s artistic journey since the 1980s in New York City and marvel at what he has accomplished with his signature tag. Once vilified, we now celebrate his artistic genius.”

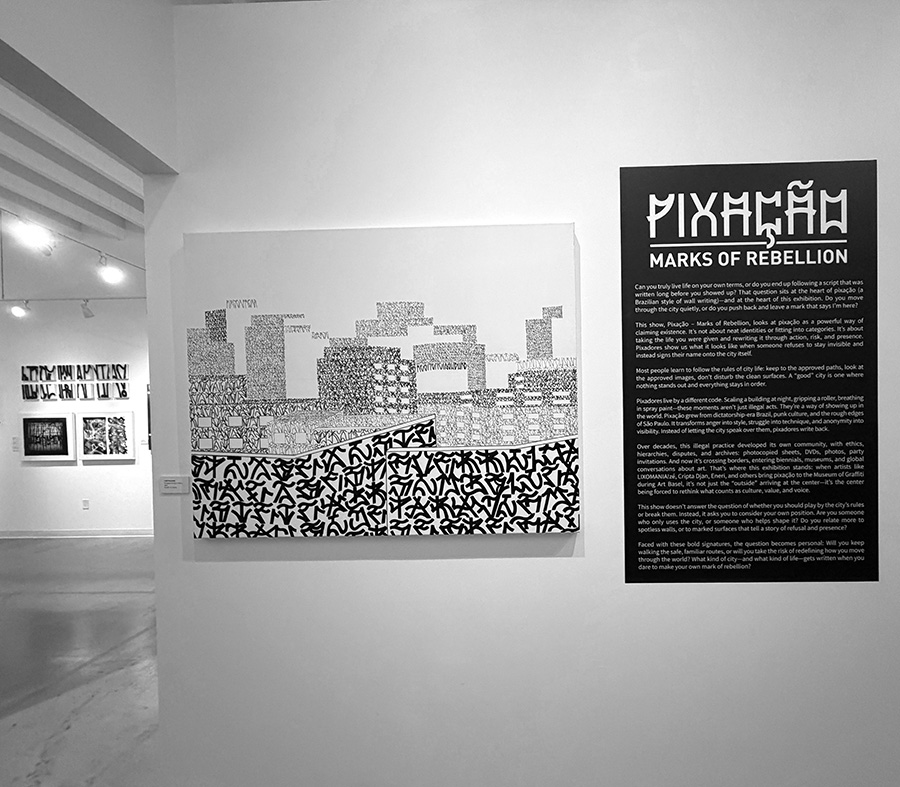

Pixação: Writing on Its Own Terms

“PIXAÇÃO — MARKS OF REBELLION” opens with a question about whether you live on your own terms or follow a script written before you arrived. The wall text situates pixação historically—dictatorship-era Brazil, punk culture, São Paulo’s hard edges—while refusing oversimplification. Before conclusions form, it names the internal infrastructure outsiders often miss: hierarchies, disputes, archives, and community memory.

When artists like LIXOMANIA!ZÉ, Cripta Djan, and Eneri bring pixação into the Museum of Graffiti during Art Basel, the question isn’t whether it’s art. It’s what it forces viewers to reconsider about culture, value, and voice.

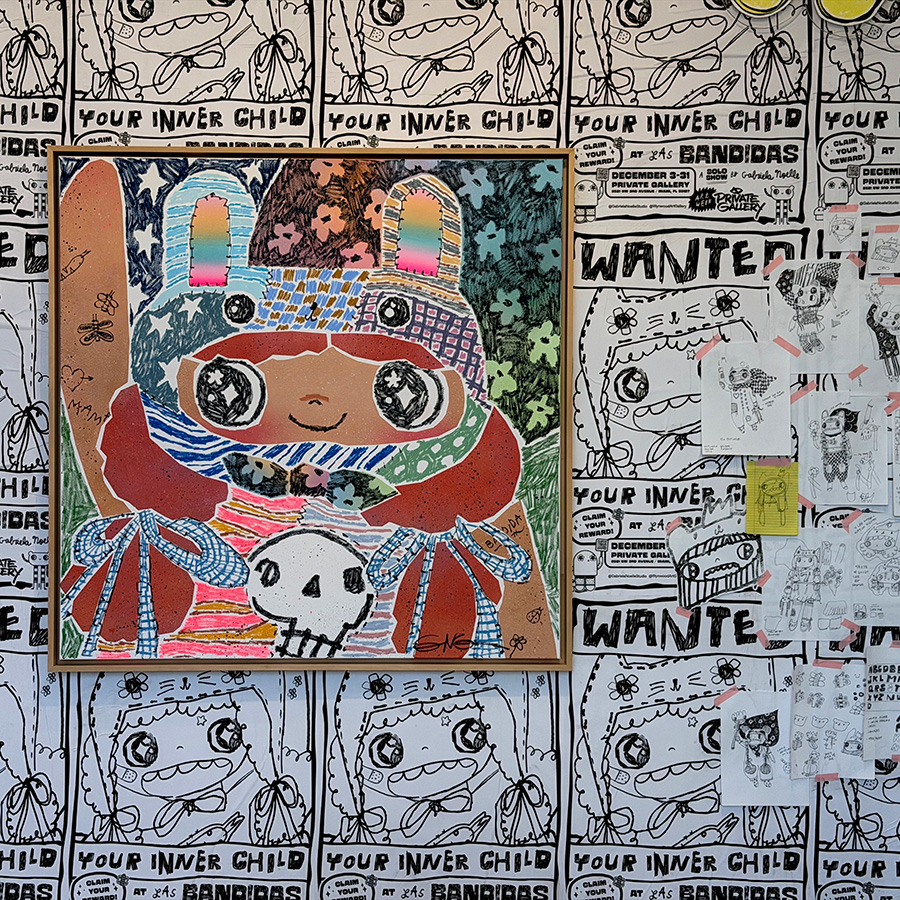

The Adjacent Economy

Adjacent Wynwood Art Gallery makes the museum’s economy explicit: a commercial-facing space where the work is translated into objects—canvases and small sculptures—without pretending that’s where any of it began. Artists who came up in the street, like UFO 907, alongside projects like Las Bandidas, sit within a now-expanded field of artists finding traction on different registers of the broader art world. Young collectors and die-hard old-school fans criss-cross, each eyeballing the other and the works for sale, well-lit and charged with sudden jolts of electricity.

Bathed in light and framed by white walls, the work is legible to a buyer while remaining tethered to the culture that produced it. This is also where familiar critiques tend to surface—often loosely aimed—circling class, race, commerce, vandalism, validation, and contradiction. The argument isn’t whether this belongs here—it’s what gets lost once it does. Most people, quietly and without much hand-wringing, agree on one thing: it’s good when artists can make a living, and it always has been. This gallery appears to contemplate the complexities, the backstories, and opens the expanse of studio expression that is global today, wide and varied, multistyled and multi-lingual.

Returning History to Its Authors

A daunting task, the Museum of Graffiti is telling the stories and assembling the language needed to explain to a broader audience how a culture built through vandalism and illegality also produced enduring forms of authorship, influence, and value. It gives voice to writers and artists who have hit the streets for more than five decades, across many cities. There is enough grammar here to choke on, and enough history to get buried under—but also enough evidence to make the tension unavoidable.

With each layer, a viewer understands why certain objects carry weight, and encounters enough names—accurate, specific, and placed in time—to keep the story from dissolving into lazy “legend” tributes. And because the guide is Alan Ket, co-founder of the museum, someone who can stand with writers in front of a newly unearthed UGA canvas and watch them realize it’s the real thing, the scholarship doesn’t feel like a lesson delivered from above; it feels like a history being returned to its authors, in public.

ORIGINS, JonOne, and Pixação: Marks of Rebellion are open to the general public MUSEUM OF GRAFFITI for information on schedules, events, and directions.

While at MOG, make sure to visit WYNWOOD ART GALLERY next door to see their current exhibitions featuring Las Bandidas, UFO907, and more.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY