Nearing two decades of this annual list, BSA has changed as the local and global street art/graffiti/fine art scenes have. Less interested in the celebrity and more interested in the people and passions that drive the need to express yourself creatively in public space, BSA has gone through whatever doors opened and a few that were slammed shut. Our shortlist for 2025 reflects a diversity within the street art, graffiti, and fine art worlds that many once assumed would become centralized and homogenized.

Sure, there is a lot of derivative drippy “street art” dreck at art fairs and on particular walls. Still, we suggest the scene is no longer best described as a single movement traveling toward institutional acceptance. We would also argue that it was never the goal, regardless of the Street Art hype of the 2010s. In an interconnected artist’s life, this ‘scene’ is a network of practices that share tools (reproduction, scale, public encounter), ethics (authorship vs anonymity, permission vs necessity), and stakes (who gets to speak in public, and how).

The common threads aren’t style, or even medium—they are circulation, context, and the social life of images. In that sense, this group of books doesn’t just document a year; it maps a portion of the expanded field where street culture, publishing culture, and contemporary art culture now overlap—sometimes comfortably, sometimes in productive friction.

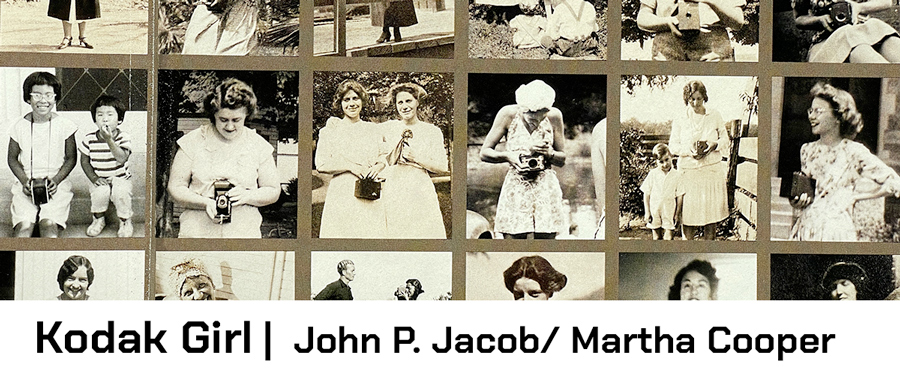

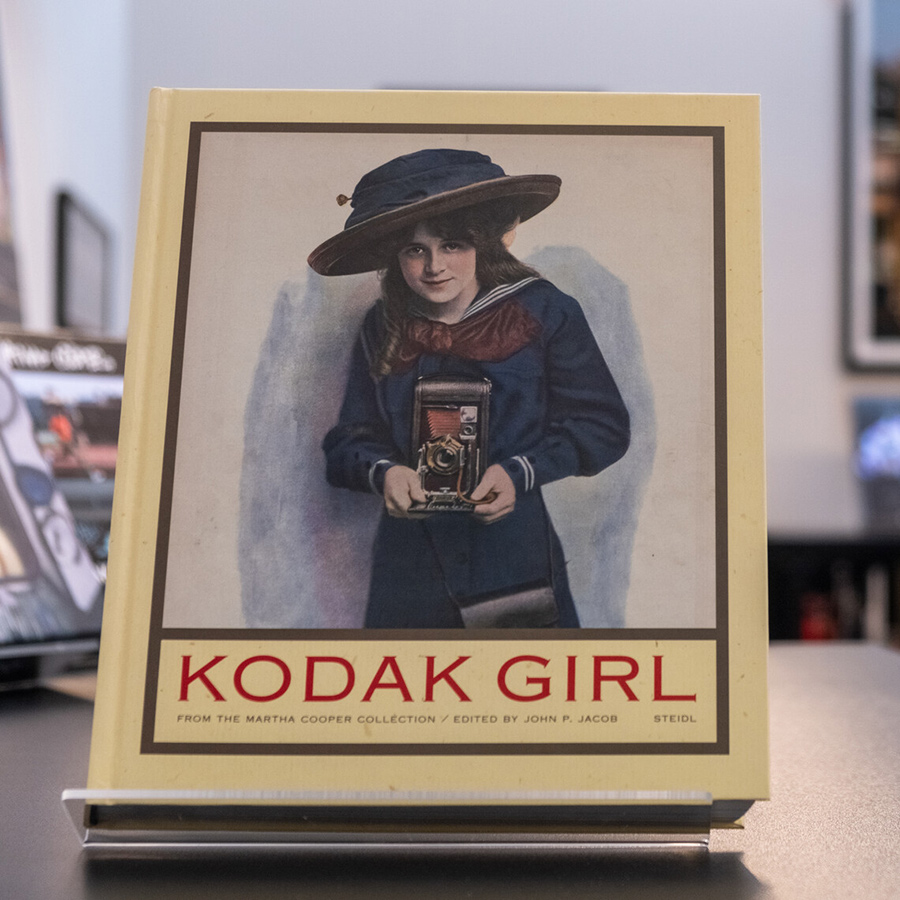

Books in the MCL: John P. Jacob (ed.). “Kodak Girl: From the Martha Cooper Collection”

Kodak Girl: From the Martha Cooper Collection. John P. Jacob (ed.). 2012

From BSA:

“Kodak Girl: From the Martha Cooper Collection“, edited by John P. Jacob with essays by Alison Nordström and Nancy M. West, provides an in-depth examination of Kodak’s influential marketing campaign centered around the iconic Kodak Girl. With a riveting collection of photographs and related ephemera, the book dives into the intersection of technology, culture, and the role of gender in the late 19th to the mid-20th centuries. It offers readers a comprehensive look at how Kodak not only transformed photography into a widely accessible hobby but also significantly influenced societal perceptions of women.

Books in the MCL: John P. Jacob (ed.). “Kodak Girl: From the Martha Cooper Collection”

Sofort alle Fenster und Türen schliessen! (Immediately Close All Windows and Doors)

Poster campaign in Basel (Switzerland), 1986, by anonymous artists to highlight the Sandoz fire disaster in Schweizerhalle. Zine photographed and printed anonymously, Basel 1986. Self-published. No longer available for purchase.

From BSA:

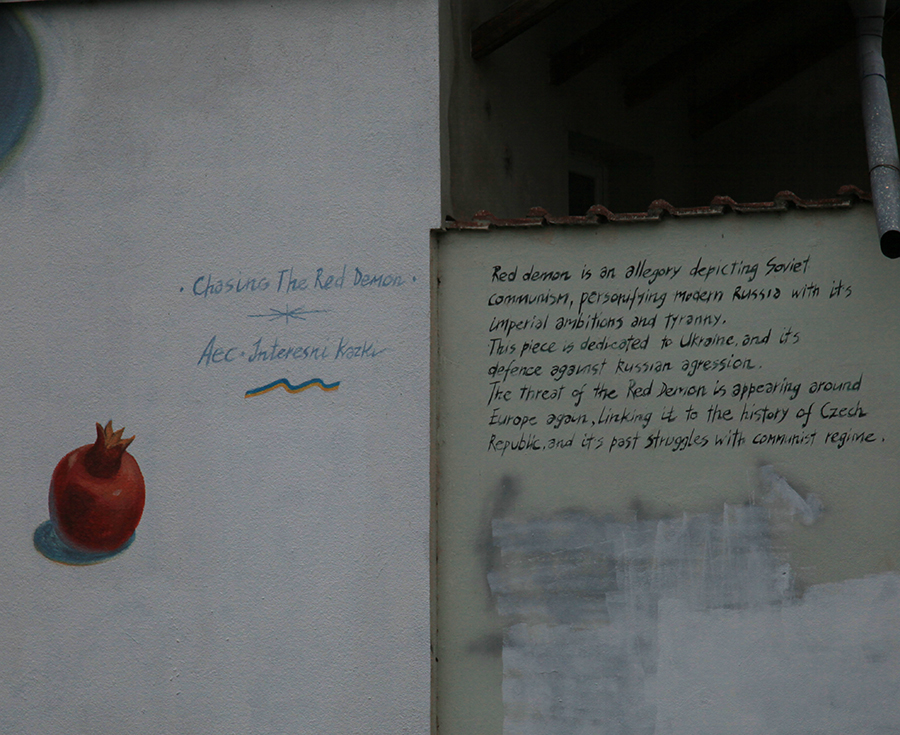

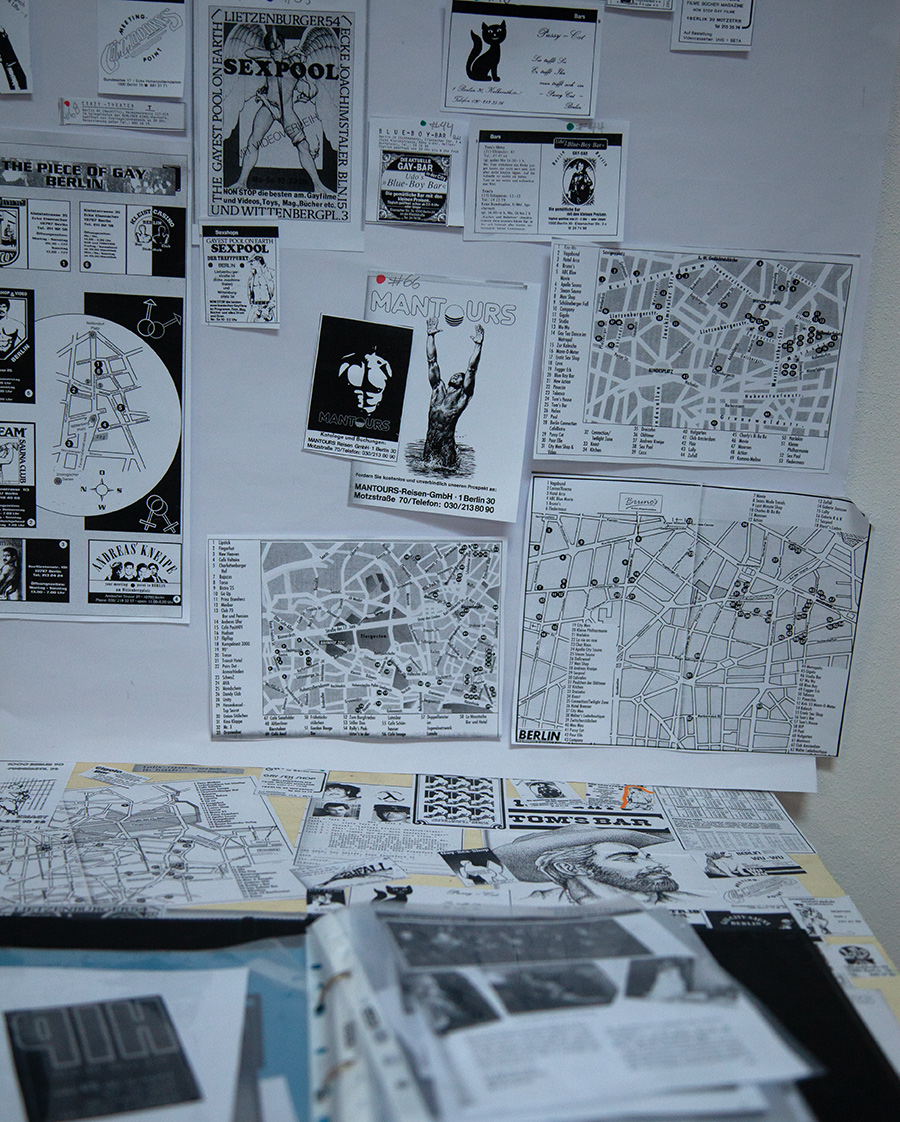

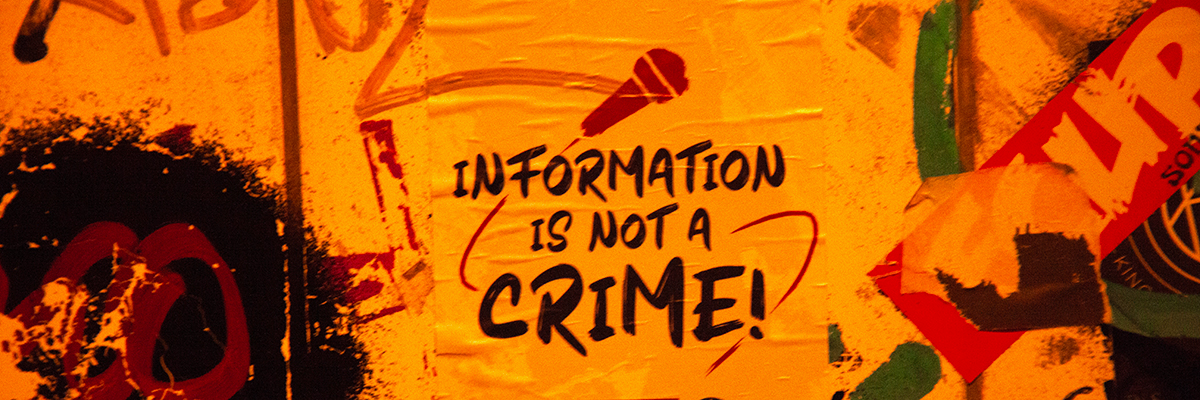

On the night of November 1, 1986, Basel was told to “immediately close all windows and doors.” A fire ripped through a Sandoz chemical warehouse, and the Rhine River ran red with toxic runoff. Thousands of fish floated belly-up, and citizens were left in fear and fury, just months after the trauma of Chernobyl【1】.

When the authorities stumbled and minimized the danger, Basel’s artists and students seized the opportunity to express themselves on the walls. Within days, in the middle of the night, activists from the School of Design plastered the city’s billboards and poster kiosks with their furious responses【2】. They worked fast, stayed anonymous, and left the streets covered with raw, hand-painted images and biting slogans.

Sofort alle Fenster und Türen schliessen! (Immediately Close All Windows and Doors)

Arek Stankiewicz & Bartek Swiatecki. WARMIOPTIKUM. Warmia, Olsztyn. Poland. 2024

From BSA:

Interpreting Warmia’s Hidden Patterns from Above and Within

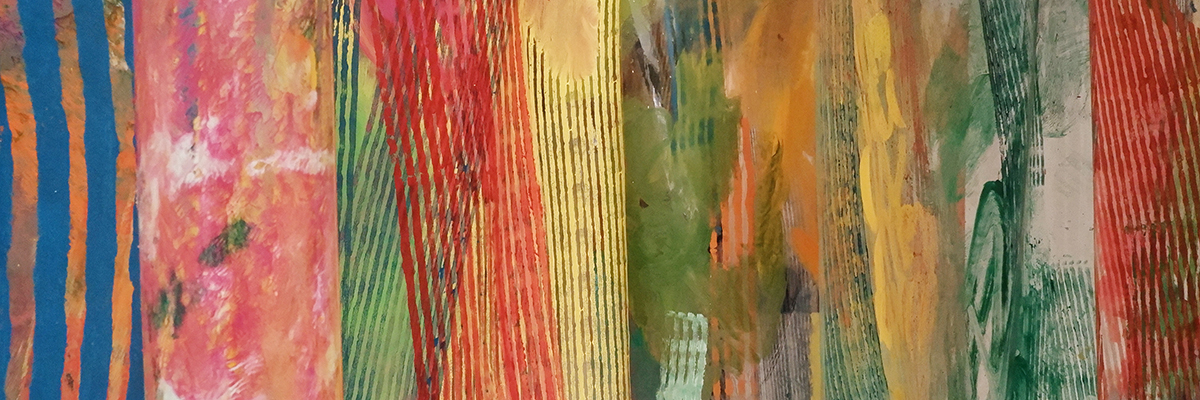

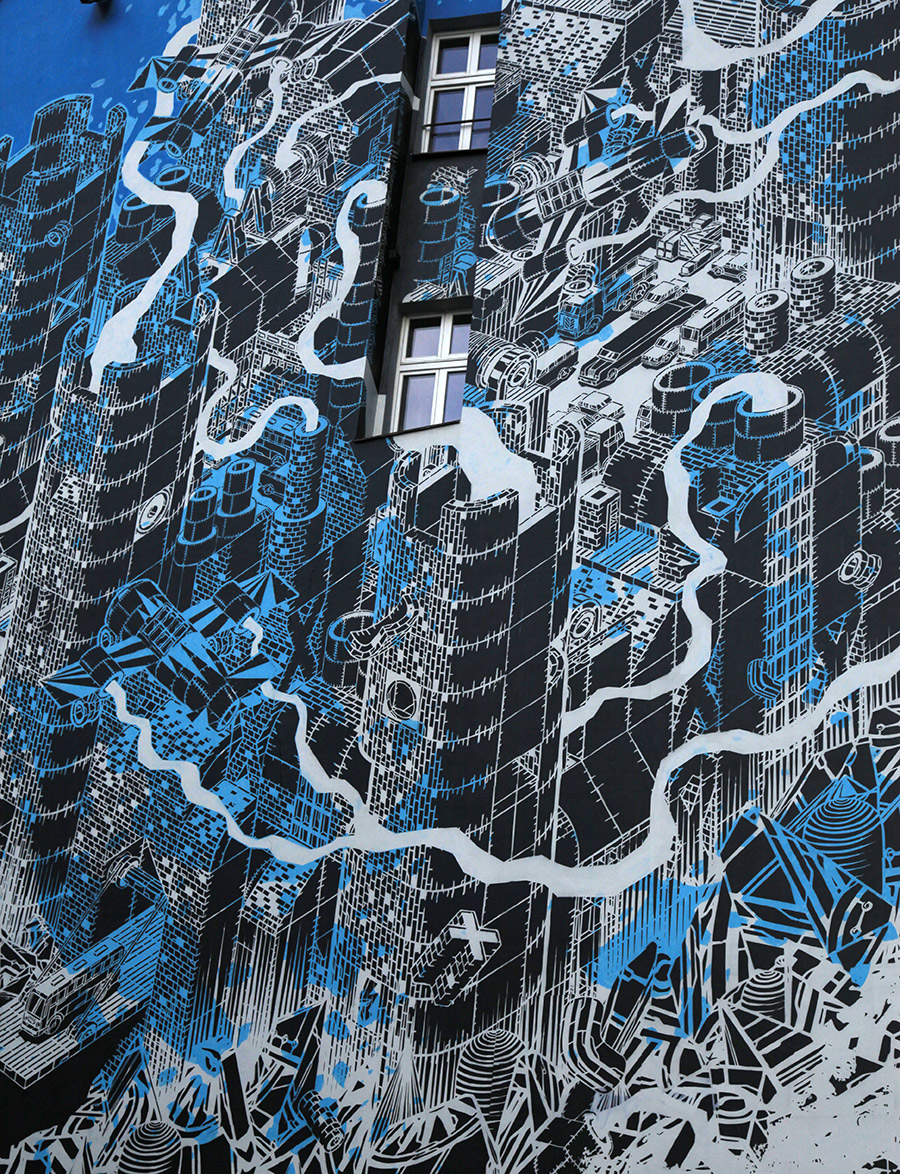

Bartek Swiatecki’s latest book, Warmioptikum, is a striking fusion of abstract painting and aerial photography, capturing the landscapes of Warmia, Poland, from a new perspective. Featuring Swiatecki’s expressive, in-the-moment paintings set against Arek Stankiewicz’s breathtaking drone photography, the book transforms familiar rural scenes into an evolving conversation between art and nature.

Swiatecki, known for his roots in graffiti and urban abstraction, takes his practice beyond the cityscape and into open fields, painting directly within the environment. Stankiewicz’s aerial lens frames these artistic moments, emphasizing their relationship with the land’s patterns, textures, and rhythms. As noted in the book’s foreword by Mateusz Swiatecki, Warmioptikum is a documentation and an exploration of how we perceive and engage with landscape, helping the reader see Warmia through “extraordinary perspectives and new, nonobvious contexts.”

Arek Stankiewicz & Bartek Swiatecki. WARMIOPTIKUM. Warmia, Olsztyn. Poland. 2024

Addison Karl. KULLI. A Natural Spring of Artwork, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Public Art, and Inspiration. Self-published. Monee, IL. 2024.

From BSA:

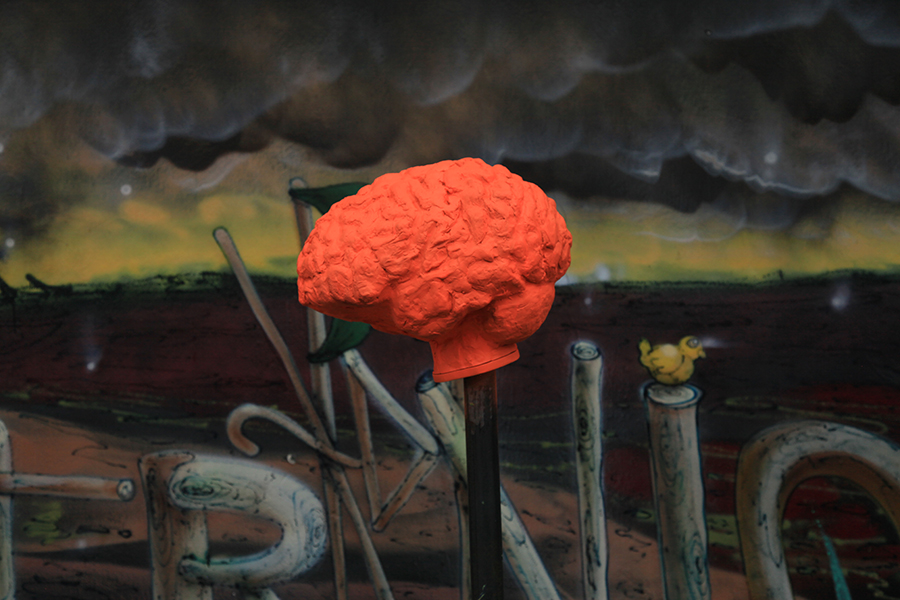

Over the last two decades of covering the street art movement and its many tributaries, one of the deepest satisfactions has been watching artists take real risks, learn in public, and mature—treating “greatness” as a path rather than a finish line. Working at BSA, we’ve interviewed, observed, and collaborated with scores of artists, authors, curators, institutions, and academics; it’s been a privilege to see where they go next.

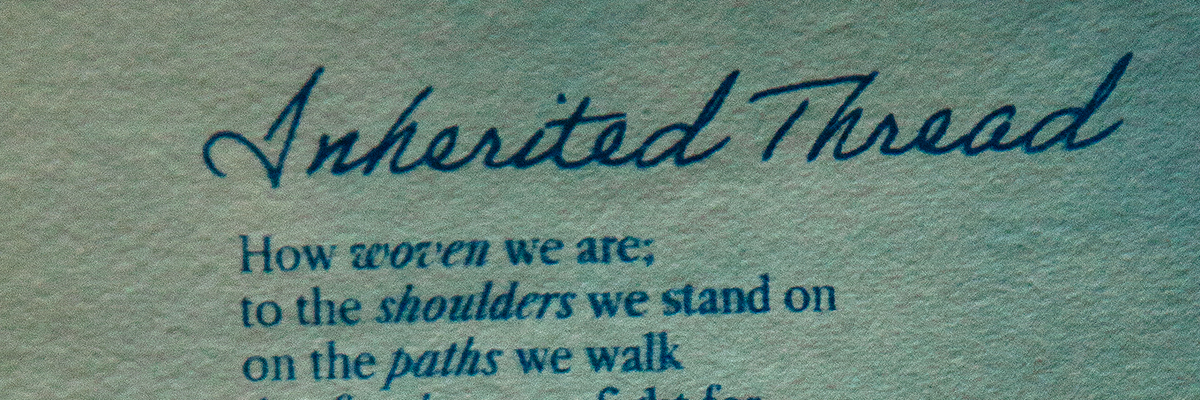

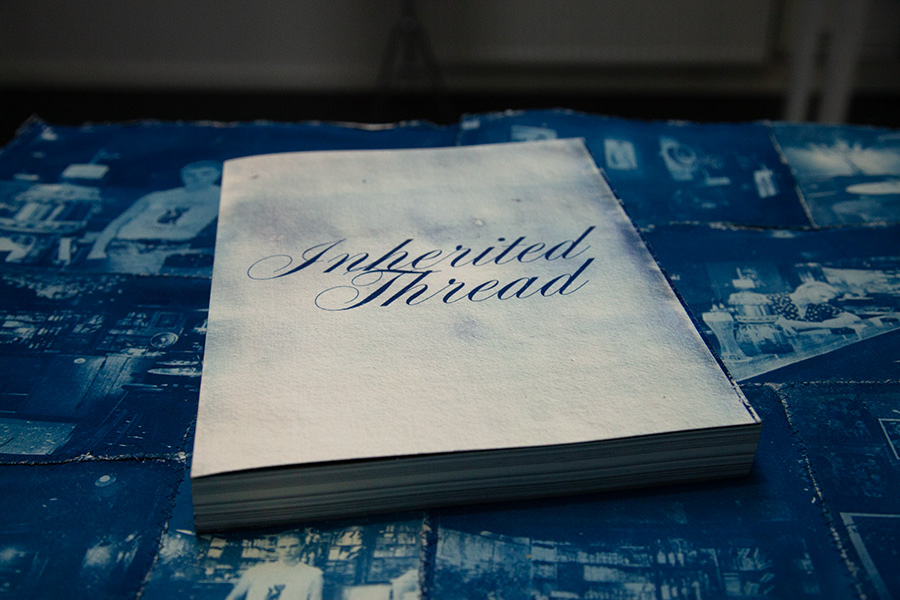

Addison Karl’s self-published 2024 monograph, “KULLI: A Natural Spring of Artwork, Sculpture, Painting, Drawing, Public Art, and Inspiration,” reads as a first-person chronicle from an artist who moved from the wall to the plaza to the foundry without losing the intimacy of drawing. Dedicated to his son—whose name titles the book—KULLI threads words, process images, and finished works across media: murals, cast-metal and glass sculptures, drawings, and studio paintings, all guided by a sensibility that treats color and material as vessels for memory and place.

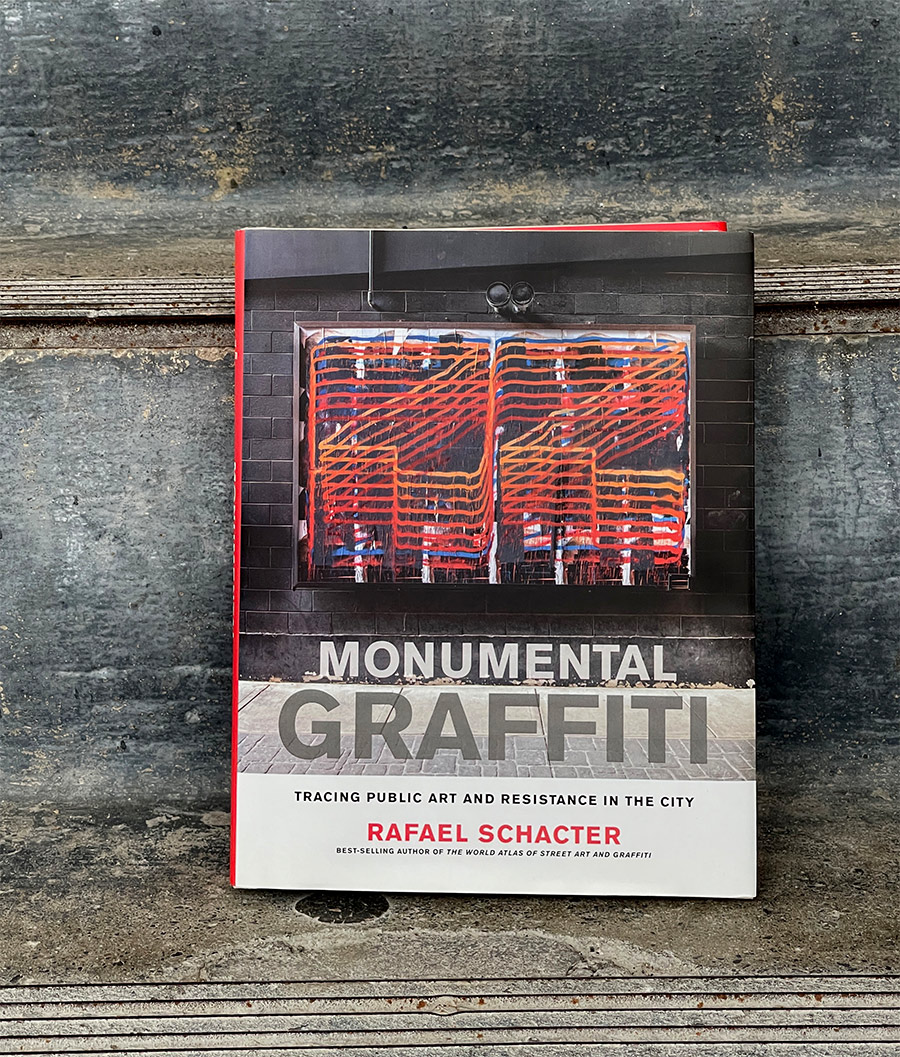

Rafael Schacter. Monumental Graffiti. Tracing Public Art and Resistance in The City. MIT Press. 2024

From BSA:

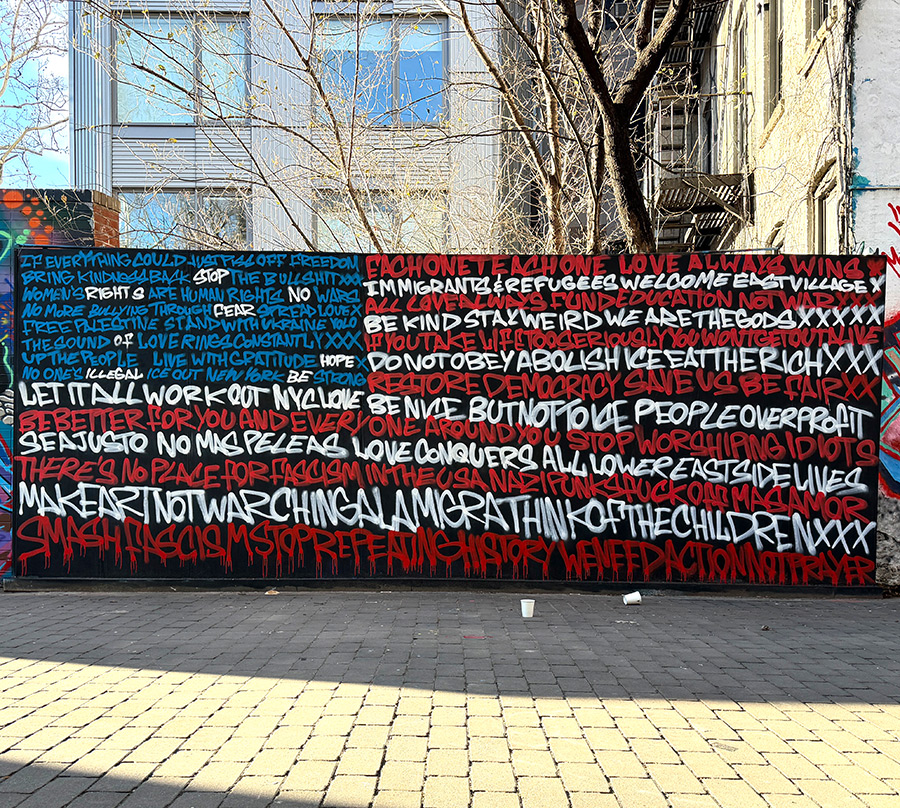

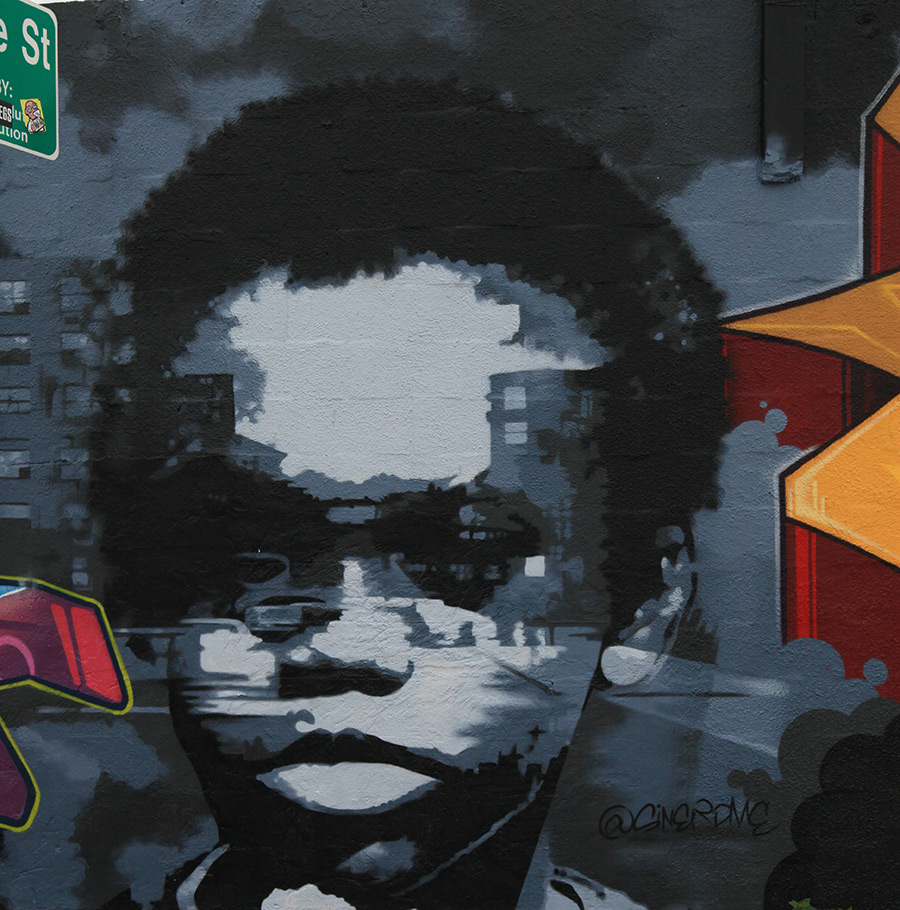

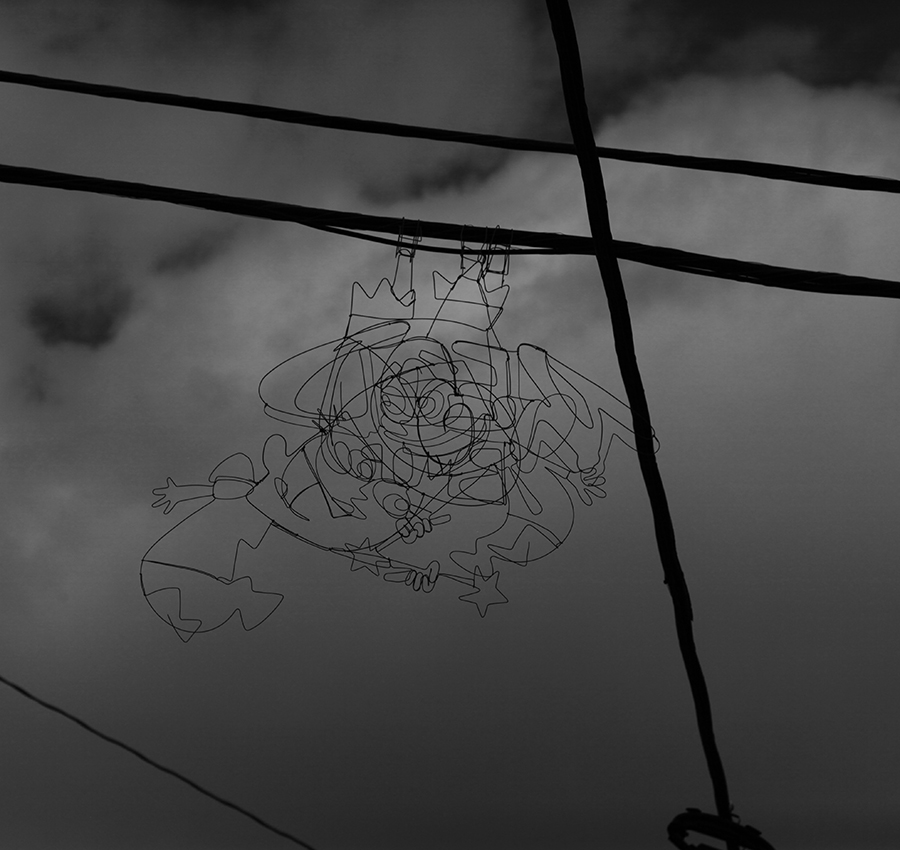

Graffiti is a living monument—an act of doing rather than keeping.

Rafael Schacter has been offering an alternative to institutional monumentality in his latest book Monumental Graffiti (2024). He buttressed his alternative view during his keynote speech for the New York 2025 Tag Conference (BSA is a sponsor). To a packed audience at the Museum of the City of New York, Schacter talked about a monumentality that is grounded in community, embodiment and the acceptance of transience as truth.

In his talk and his book, the London-based art historian argues that monuments and graffiti can illuminate each other: monuments don’t need to be grand or permanent, but can be understood—as their Latin root monere suggests—as acts that remind, advise, or warn. Drawing on counter-monuments and non-Western traditions, he would like to redefine monuments as socially and emotionally engaging public artifacts that may be ephemeral, community-driven, and conceptually monumental rather than physically imposing.

Rafael Schacter. Monumental Graffiti. Tracing Public Art and Resistance in The City. MIT Press. 2024

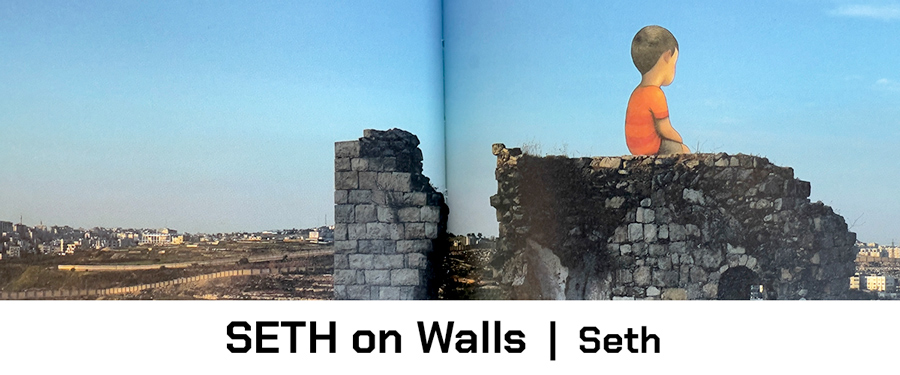

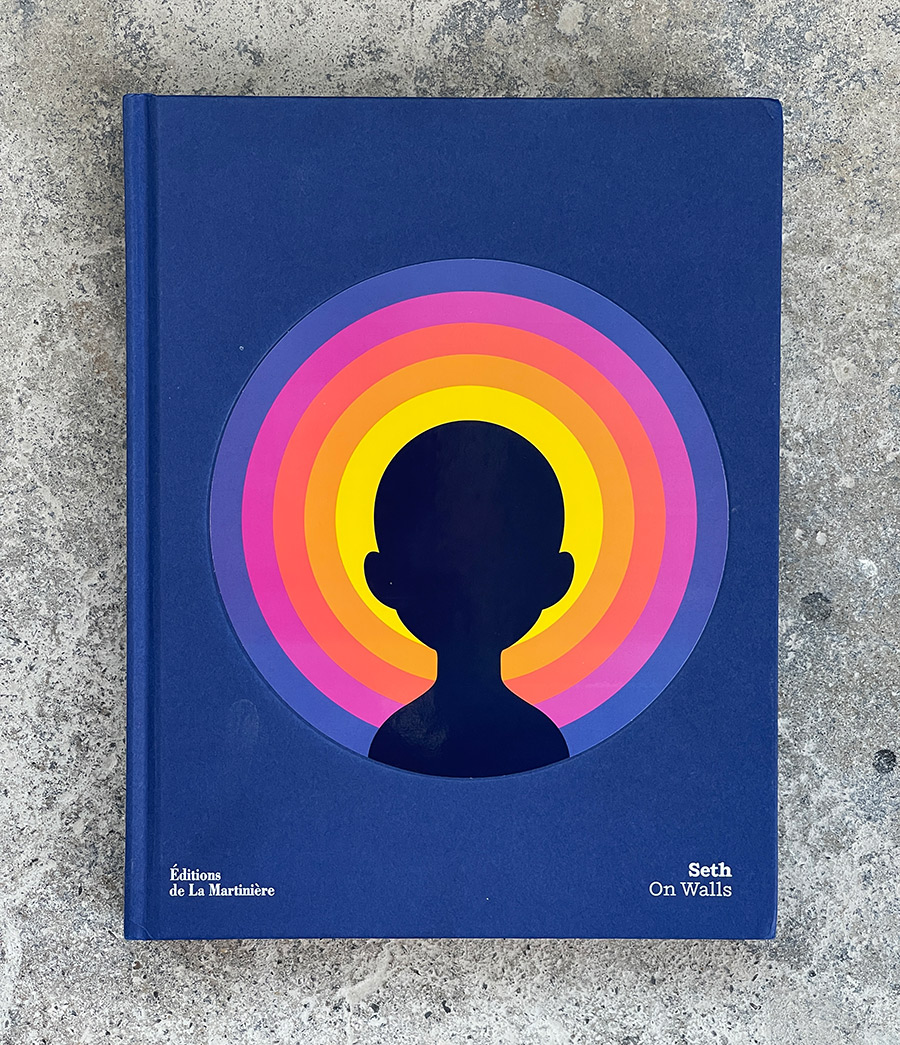

SETH on Walls. Editions de La Martiniere. 2022. Distributed by Abrams. An imprint of ABRAMS, 2023.

From BSA:

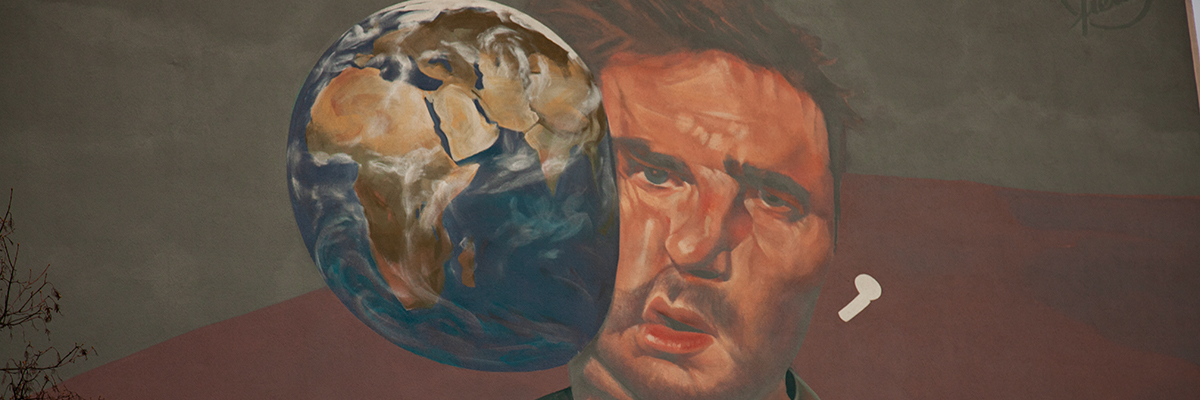

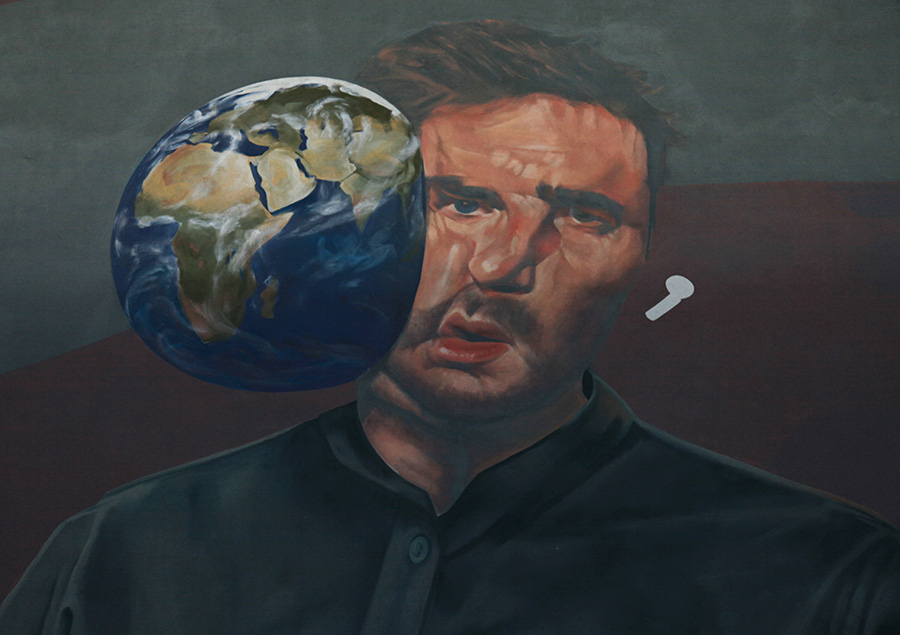

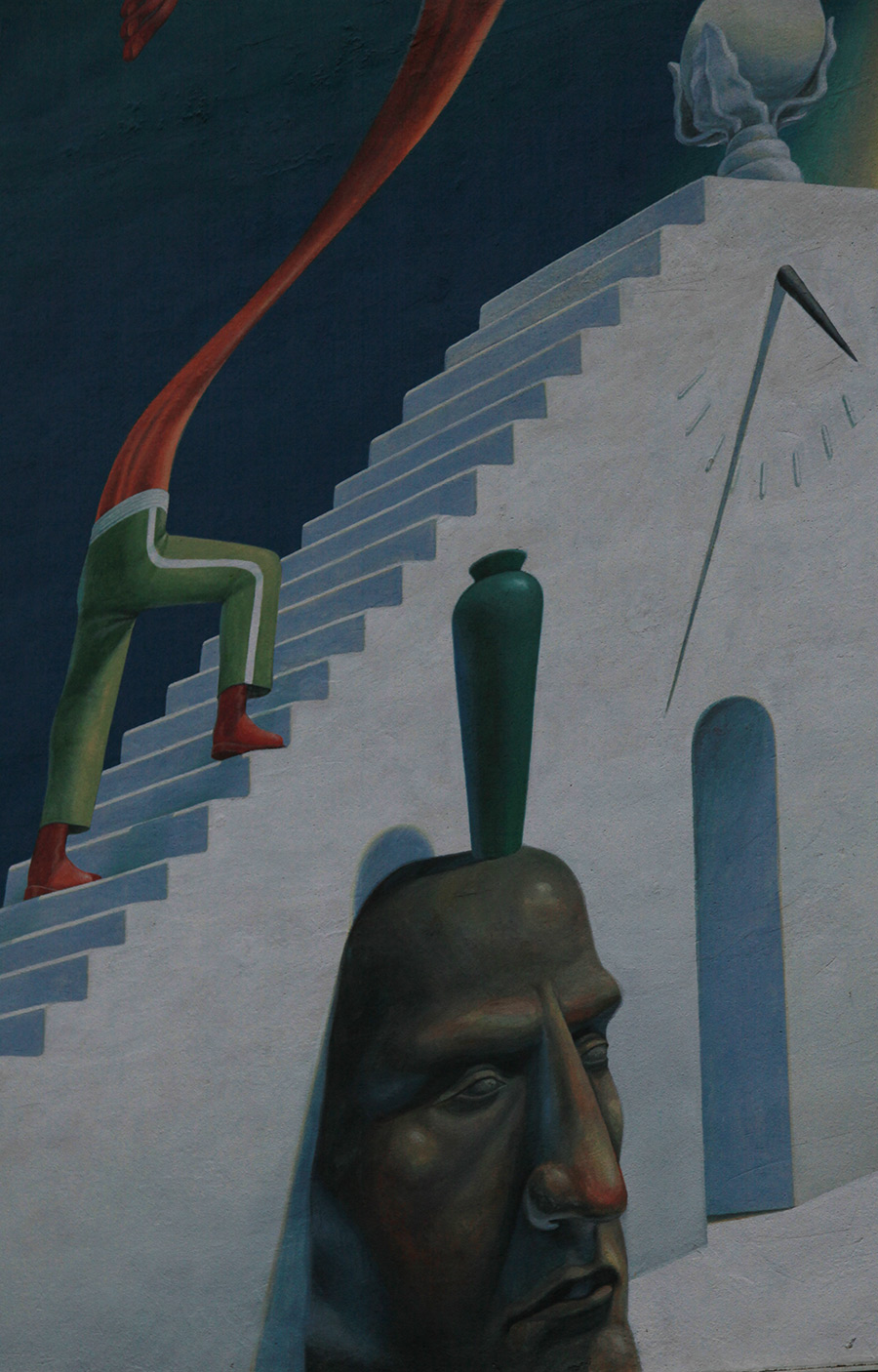

“In a world where the system alienates the most vulnerable, imposing a cynical or pessimistic outlook seems impossible to me,” says French street artist Seth. “Walls remain the space of resilience. Unlike cartoons, which leave no room for ambiguity, the choice to interpret a mural is essential. The curious are free to discover the hidden meaning.”

His new book “Seth On Walls” candidly offers these insights and opinions, helping the reader better understand his motivations and decisions when depicting the singular figures that recur on large walls, broken walls, and canvasses. A collection that covers his last decade of work in solo shows, group shows, festivals, and individual initiatives, you get the central messages of disconnection, connection, and honoring the people who live where his work appears.

SETH on Walls. Editions de La Martiniere. 2022. Distributed by Abrams. An imprint of ABRAMS, 2023.

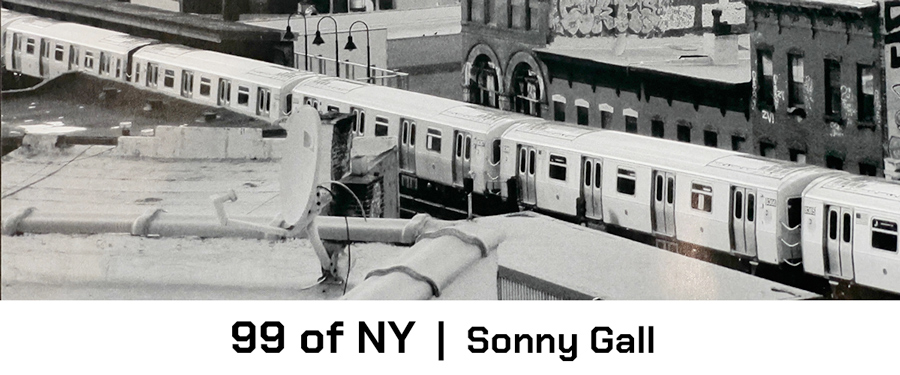

Sonny Gall. 99 of NY, released by King Koala Press with text by Mila Tenaglia. 2025.

From BSA:

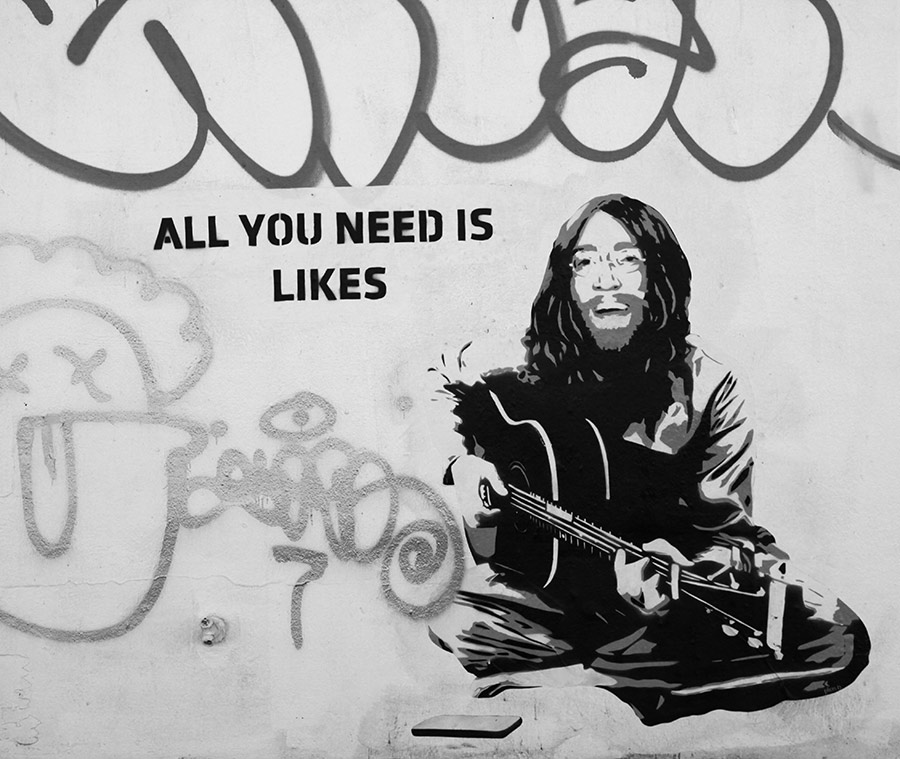

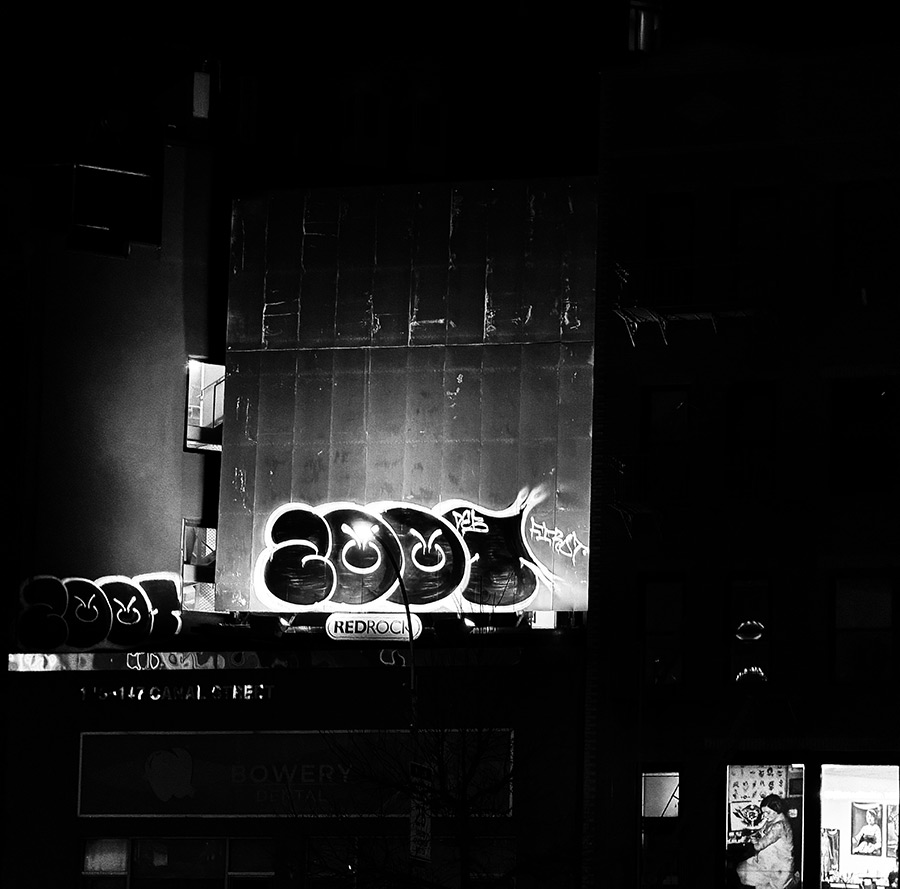

Described by the publisher as “a compositional and documentary endeavor that unfolded naturally over the course of a decade,” 99 of NY gathers 99 photographs across 110 pages, printed in both color and black and white, in a durable hardcover, album-sized format. True to King Koala’s limited-edition tradition, it’s a finely produced object — modest in scale and rich in substance — that rewards slow looking and quiet reading.

Gall’s images vibrate and render when leaning toward the overlooked: empty lots in Queens, warehouse walls, families at home, scattered pigeons, playgrounds under scaffolding. They are fragments of a living city seen with patience and affection, moments that feel at once offhand and deliberate. Tenaglia’s accompanying texts deepen those impressions without overexplaining, their language as sharp and unadorned as the photographs themselves, yet evocative of the unseen – with a poetic wandering appropriate for the attitude of discovery. Together they capture what it means to move through New York — not as spectacle, but as encounter.

Sonny Gall. 99 of NY, released by King Koala Press with text by Mila Tenaglia. 2025.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY