Across the heart of Belfast, murals serve as powerful testimonies to the struggles and aspirations of people across the globe. Bill Rolston, a revered photographer and academic, has dedicated his career to capturing and archiving these poignant and powerful expressions. His current exhibition at the Ulster Museum, “Drawing Support: Murals, Memory and Identity,” serves as a compelling narrative of conflict, resistance, and identity, offering a lens through which we can understand the deeper implications of these artworks. Rather than focusing on the murals of “The Troubles” exclusively, we broaden the topic here to a variety of other forms of political expression on the street we found during our visits to Belfast and Dublin.

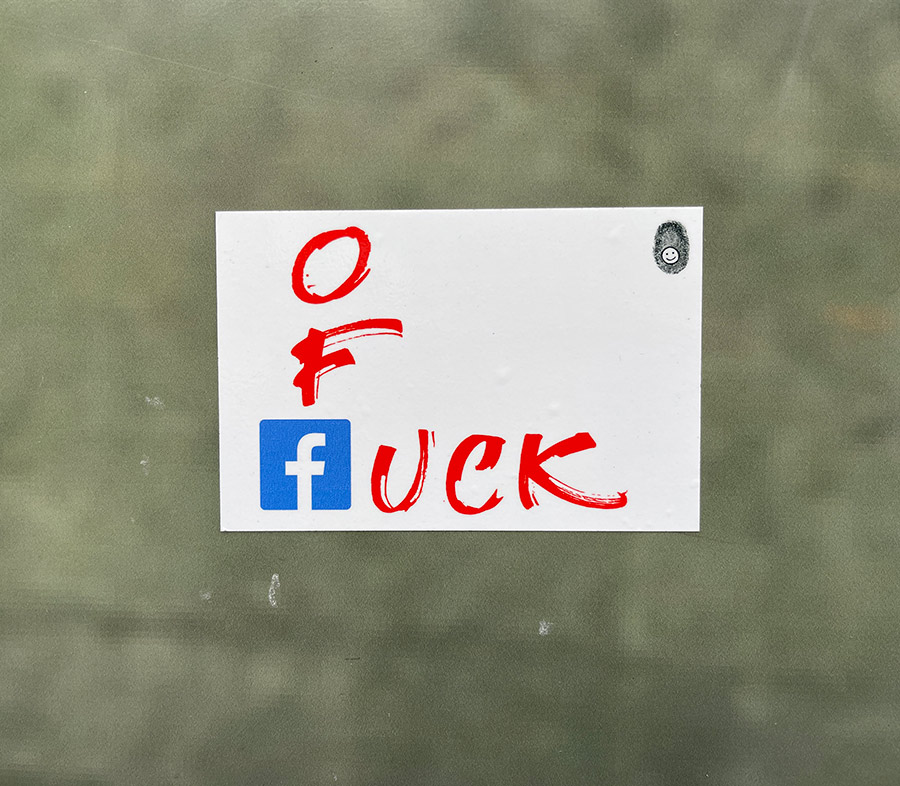

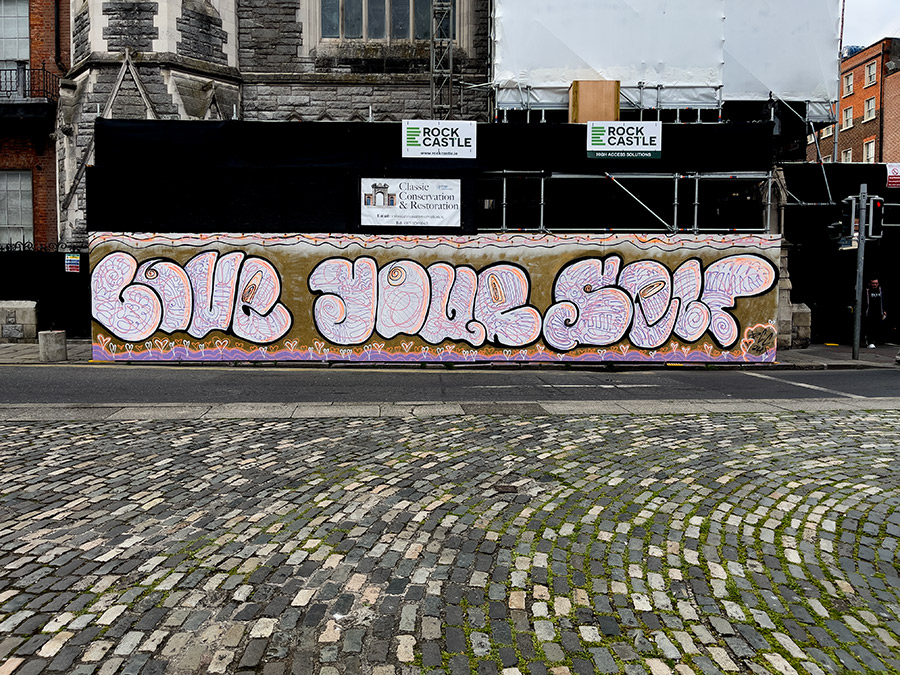

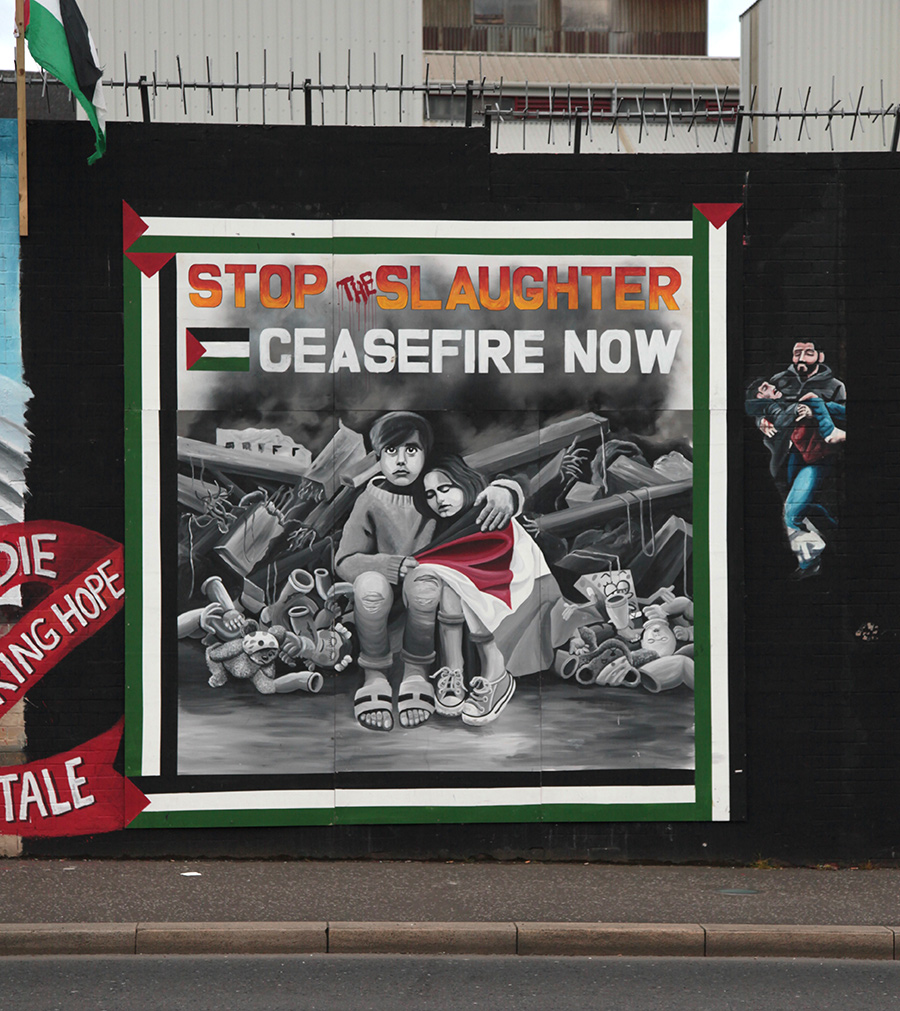

Political expressions in Dublin tend toward the modern styles of street art, and students at Trinity College were stalwart in their protests about Palestine a few weeks ago when we visited. The political murals in Belfast that address current global conflicts, such as the war in Gaza, are primarily located in the Falls Road area. This area is renowned for its rich history of mural art, particularly in the context of political and social issues. The International Wall on Divis Street, which intersects with Falls Road, is a prominent site where murals addressing global conflicts and peoples’ movements can be found. These murals often reflect themes of resistance, solidarity, and international struggles, connecting local issues with global ones. For instance, murals on the International Wall have depicted support for Palestinian rights, drawing parallels between the struggles in Northern Ireland and those in Palestine.

While Dublin went for the big statement of a 6 floor banner saying “Ceasefire”, the Belfast murals bring attention to international issues and foster a sense of global solidarity by extension, serving as a visual dialogue between local communities and greater movements. They provide a powerful medium for political expression and awareness. Rolston’s extensive documentation of murals pertaining directly to “The Troubles” provides a foundation for understanding how the visual language of murals has evolved to encompass broader global concerns. The murals are not just about the past but about our shared human condition and the ongoing fights for justice and peace.

Some historians say that the tradition of political murals in Belfast dates back to the early 20th century when a likeness of King William of Orange was painted on a bridge in the city. Accordingly, this act may have marked the beginning of what Rolston describes as the “longest continuous tradition of political murals in the world.” The murals initially focused on local political and historical events, particularly related to the Protestant Unionist community. However, over time, they evolved to include a wide range of topics, including international solidarity.

One prominent theme in the murals at this moment is the plight of the Palestinian people. The very fresh murals depict the deprivation and attacks on Palestinians, reflecting the intense international cry for Israel to cease its bombardment of Gaza. For viewers, these murals serve as a bridge between the struggles in Belfast and those in the Middle East, illustrating the universal language of resistance and solidarity.

Another critical issue addressed in the murals is the problem of affordable housing in Belfast, which has resulted in homelessness and a reliance on hostels. The murals capture the stark realities faced by many in the city, drawing parallels to global economic inequalities. Murals have long been a way for communities to voice their grievances and demands for change.

Lastly, the theme of political imprisonment is evident, with comparisons drawn between Irish hunger strikers like Bobby Sands and Palestinian hunger striker Kader Adnan. These murals commemorate the sacrifices made by individuals fighting for their political beliefs and what is regarded as the right to be recognized as political prisoners. They serve as a memorial and a call to action, reminding us of the ongoing struggles for human rights and dignity.

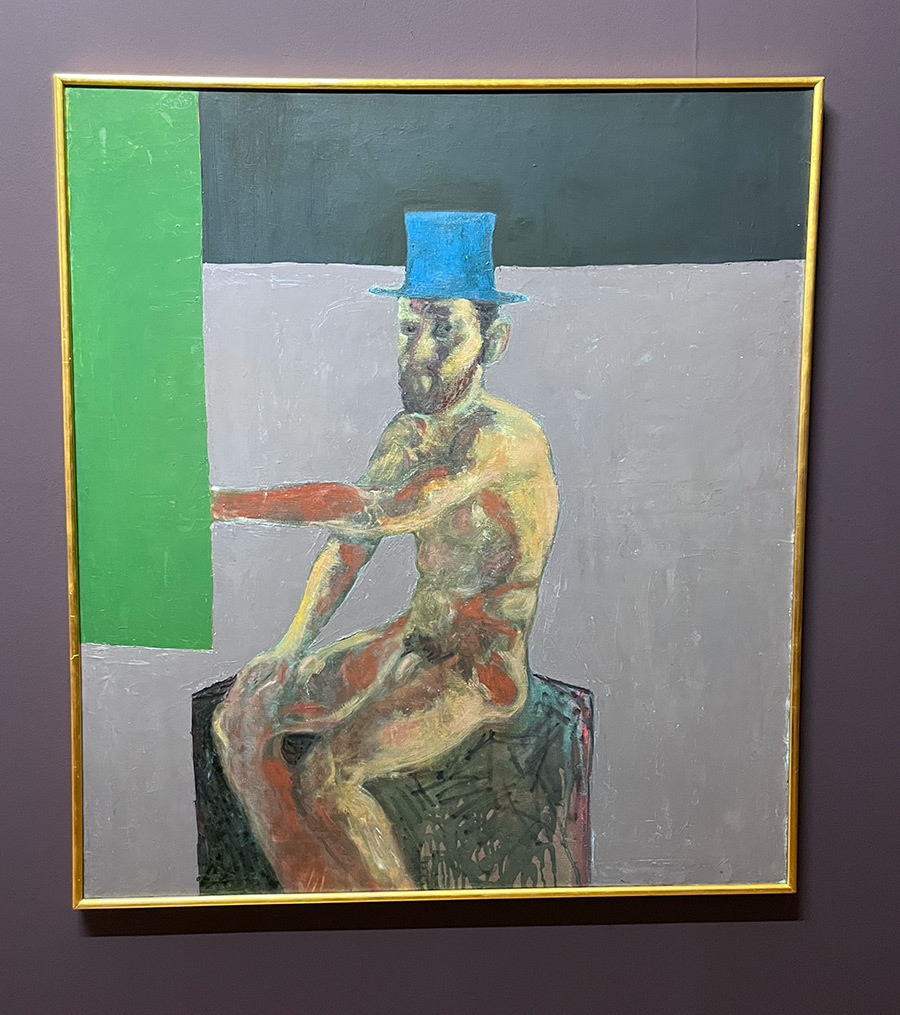

In addition to the politically charged murals, a new generation of talented international and local street artists in Belfast is making its mark. These artists, equipped with stunning technical skills, photorealistic painting and illustration styles, pop culture characters, and painting techniques more frequently associated with formal academic training from the university, often avoid explicitly political themes. Their work adds a fresh aesthetic to the city’s mix of publically painted walls and has found fans across different communities. Despite the diverse themes, there appears to be room for both traditional political murals and newer street art, creating a varied, rich, and dynamic mural culture in Belfast.

The murals on the International Wall and throughout the Falls Road area continue to play a crucial role in voicing political opinions and fostering a sense of community. We also saw a few politically themed walls in Dublin, but we weren’t there long enough to fairly say we had a suitable survey. Collectively, these proudly public expressions stand as a testament to Ireland and Northern Ireland’s enduring spirit of resistance and its commitment to solidarity with oppressed peoples worldwide.

For more detailed information, you can explore resources from the Museum of Orange Heritage and other historical sites in Belfast, which provide context and deeper insights into the city’s mural tradition.

Some resources:

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY