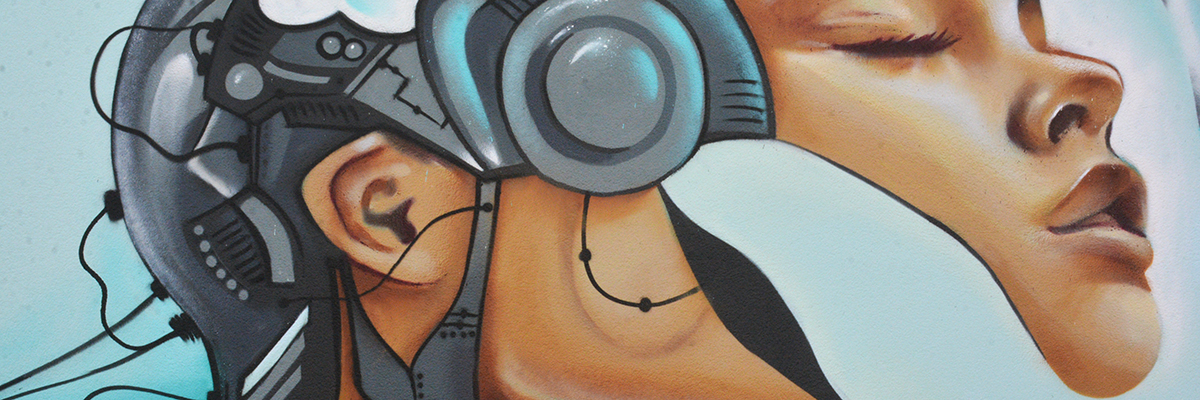

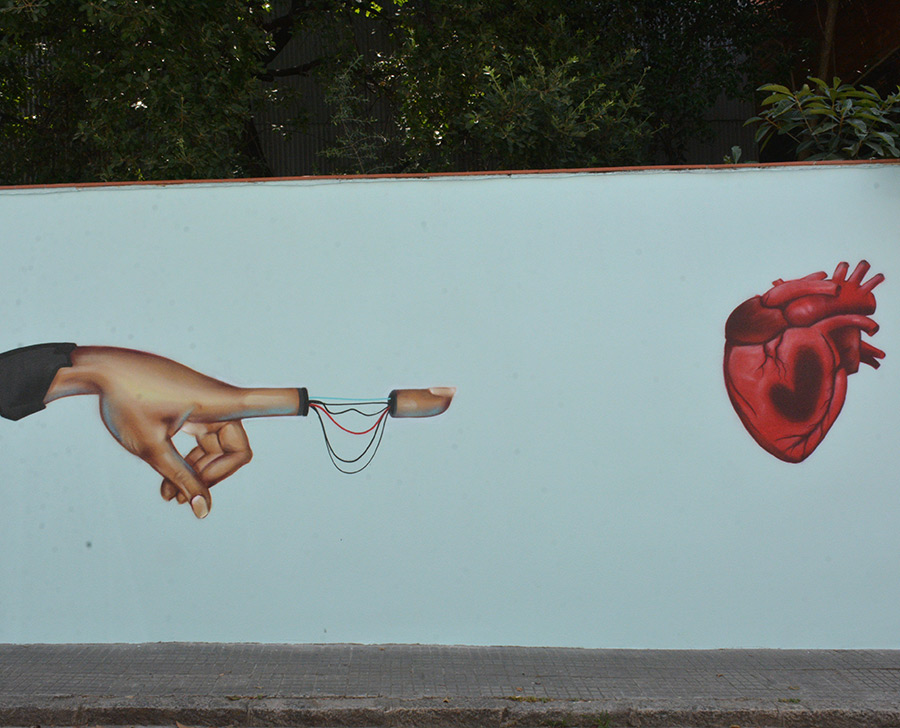

For three days in early June, the streets of Mollet del Vallès echoed with the clatter of ladders, the hiss of spray cans, and the upbeat pulse of DJs and market stalls. Artists from across Spain and beyond—including Laia, Uriginal, Sfhir, Lily Brik, Digo.Art, and Zurik—brought their visions to life on walls around the city, turning otherwise ordinary facades into large-scale, camera-ready installations. At first glance, the scene resembled the familiar format of the community-driven mural festivals that have blossomed across Europe over the past two decades. But here, the origin story takes a turn: this wasn’t a grassroots uprising to reclaim public space. This was a polished production by a commercial mural company with a massive artist roster and an even bigger understanding of branding, translating the original aesthetic of rebellion into a marketable vibe.

It’s easy to feel a pang of cynicism at what looks like another chapter in the ongoing domestication of street culture. Born in the neglected and often criminalized neighborhoods of 1970s New York, graffiti and the young brown/black/white kids who created it emerged with defiance, urgency, and a distinctly anti-authoritarian voice. The DIY energy and coded visual languages that fueled the subsequent Street Art scene once sparked public outrage and discussed topics that moved conversations on the street, but sometimes now are replaced with client briefs and sponsored walls. The mural isn’t a transgression—it’s a deliverable. Need a splash of urban edge for your brand? Book a mural. Want to boost team morale? Gather the staff for a graffiti-themed bonding exercise.

But the story doesn’t end there. Many of the artists involved in these commercial projects are veterans of illegal walls and train yards. They bring serious technique and deep cultural fluency to every surface they touch. And here lies the paradox of contemporary muralism: the best of these artists walk a fine line between selling out and showing up, managing to deliver public art that retains authenticity even when it’s wrapped in a marketing package. For some, the deal is worth it—access to large walls, financial stability, and the freedom to paint without looking over your shoulder.

We don’t need to mythologize the past to see how far things have shifted, and in many cases, improved. Some of the earliest street art festivals were organized by galleries and business owners who represented the same artists. Presumably, these artists are helping to pay the rent and developing their body of work. As “outside” as it once was, Street art is no longer the outsider; it’s part of the cultural toolkit, rolled out to energize neighborhoods, attract foot traffic, and present celebratory versions of “local identity.” The murals in Mollet del Vallès may not spark revolution or defy authority, but they do offer a snapshot of where street art stands today. This is what happens when “counterculture” trades its balaclava for a business card and becomes “culture”.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY