Like graffiti writers sharing black books and styles, BSA Writer’s Bench presents today’s greatest thinkers in an OpEd column. Scholars, historians, academics, authors, artists, and cultural workers command this bench. With their opinions and ideas, we expand our collective knowledge and broaden our appreciation of this culture ever-evolving.

by Igor Ponosov

Russian Urban Art: Poetry, Philosophy, and Manifestos in the Streets

In the interest of defining specific areas of the study of Russian Urban Art, I’ll highlight here three main periods that I think are important in the development of these forms of urban art: the 1910s–20s, the 1990s, and the current era. From my perspective, each period was usually born during crisis and revolution, went dead after a few years, and then came to life slowly again. It was this circular pattern that I am trying to define in my recent book Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts, but here I want the focus to be more specific.

I. 1910s–20s

In the 1910s, before The October Revolution, a few interesting Russian art groups and associations were founded. Most interesting of them were Bubnovyj Valet (“Jack of Diamonds”) and Osliniy Khvost (“Donkey’s Tail”), which rejected the nineteenth-century traditions of academicism and realism. In their exhibitions, artists showed their own work alongside children’s works, painted Moscow commercial advertisements, and normal street signs. Artists also tried to appropriate everyday objects into their own works.

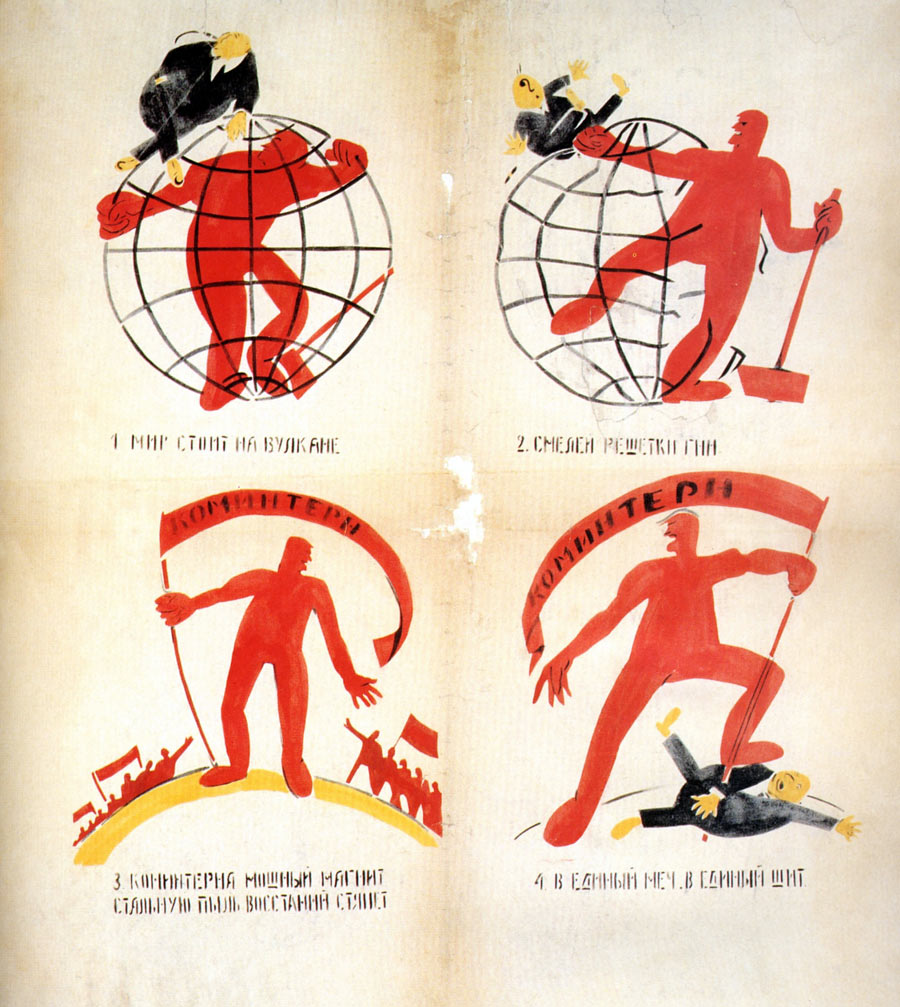

It was imperative for many artists to make rebel art, art based on folk and naïve art, and that it was influenced by Lubok – a style of graphic print containing narratives derived from literature, religious stories, and popular tales. The Lubok usually was a decoration in Russian village homes, and it became popular during the last half of the 17th century. Before the Revolution in 1917, this kind of visual form was used by many avant-garde artists, including groups such as Bubnobyi Valet and Osliniy Khvost. The well-known artist and founder of Suprematism, Kazimir Malevich, also used Lubok for patriotic paintings in the 1910s, just before creating his painting Black Square.

Some artists appropriated the same graphic style of Soviet propaganda after the Revolution, and not only in the streets. One of the most notable and significant examples of that were the Agit-trains; mobile “education” pavilions that traveled the country and featured Lubok-style paintings on the exterior of the train cars along with ROSTA posters, that were part of a massive multi-year propaganda campaign promoted by the Russian Telegraph Agency beginning in 1918.

One of the most active artists contributing to that program was poet, playwright, artist, and actor Vladimir Mayakovsky, who created hundreds of images for it. During the crisis, just before and after the Revolution, some of the most interesting art practices that blossomed and went out to the streets contained influences from these manifestos, new anti-religion narratives, and experimental poetry based on folk culture and text. These art practices are not Street Art, as we currently know it, but this is one of the first important waves for the birth of this form of contemporary art. It is also here that it is possible to see two important specific aesthetic influences – the Lubok graphic style and the text-based street manifesto – both of which were used and transformed by Russian Street Artists many years later.

II. 1990s

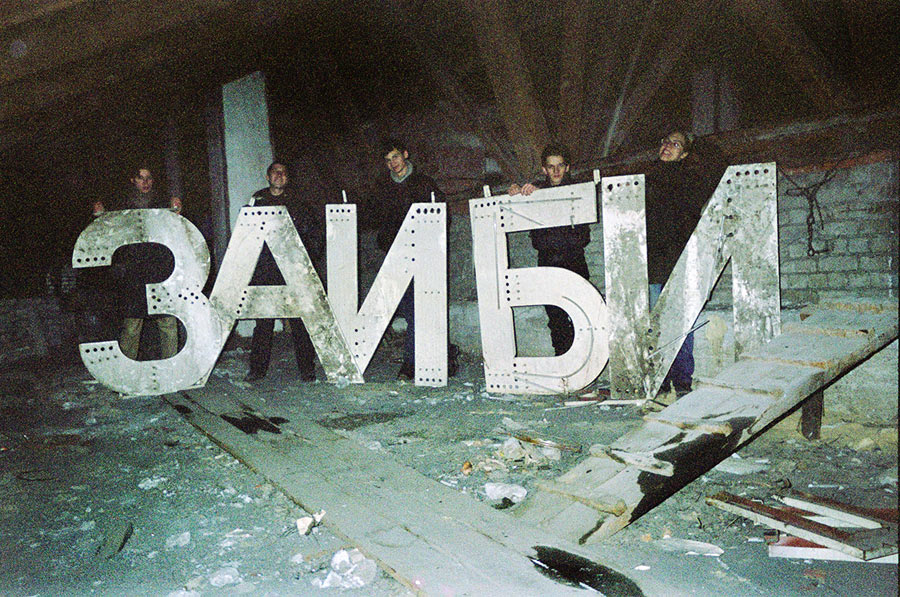

A new wave of critical and radical art movements arose in the 1990s after the USSR fell. The political shifts initiated an economic crisis, but at the same time, a freedom of speech and a new market system began developing. In many Russian cities, but especially in Moscow, new art groups were founded, represented was called an ‘Actionism’ movement. Politically and socially engaged street actions were produced by many groups such as E.T.I. and zAiBi, and artists such as Alexander Brener, Anatoly Osmolovsky, Oleg Kulik, and many others.

Like the avant-garde works of the 1910s, these actions were political and radical for sure, and at the same time, the artists were close to the people in a conceptual way. Their actions were based on poetry, literature, philosophy, and provocation; a possible illustration of the deep economic and cultural crisis the people were going through. The works revealed a certain ‘wild life’ of the Russian people, who after the fall of the Soviet Union began to feel broken and like they had been tricked. Bold, radical urban actions marked these first steps towards the return of an informal art activity on the streets of Russian cities.

The feeling of freedom, permissiveness and the lifting of censorship on Western culture gave way to new informal urban movements. These movements began to actively penetrate youth culture and social classes even during Perestroika[1] in the 1980s but fully developed afterward. Rock culture and Hip-Hop, with its street break-dancing and graffiti, were among the movements flourishing at this time. The Graffiti subculture arrived in the USSR in the 1980s. At the same time break dancing was becoming popular, dancers became the unofficial guides of Hip Hop culture, adopting dance techniques and creating decorative scenography for their performances. Graffiti, poetry, and literature slowly began to be mixed and recombined by Russian Street Artists, who have tried to find not only a ‘style’ but an identity and a new visual language to frame this new kind of street culture. Some artists continued to produce avant-garde forms based on simple geometry. Still, others slowly began to work more with local culture – incorporating aspects of the Lubok style and using anti-capitalist messages, writing short poems, tales, and manifestos in the streets.

“No Future” and “Street Art is Dead”

As a representation of the early 2000s, I want to mention the Rus crew, which started to adopt global graffiti based on nicknames in the Russian language at the turn of the century. Same time graffiti artist Kirill Kto started to use some Russian quotes and questions in the streets. In 2006 with other graffiti writers, Kirill founded a group called No Future Forever. Based on conspiracy theory and inspired by antiutopian ideas, the members produced many critical street messages in a trash/ugly graffiti style, advancing some naïve narratives and manifestos. Another person who is emblematic of Russian Street Art is Pasha 183. His naïve messages and simple style present him as a sensitive person, but at the same time as a radical anti-capitalist artist. He combined image and text perfectly for his street messages, exploring Moscow’s underground and projecting his Underground Light Art (U.L.A) images on walls.

In 2008 Russian Street Art began to shift away from the innovative and experimental practices of the past. I think it happened because 2007–2008 was a time of economic prosperity in Russia, and it is possible that Street Art needs a crisis or something to push against as a kind of grassroots, activist, protest art form. This kind of mood also can be traced outside of Russia; the British curator, researcher, and anthropologist Rafael Schacter describes 2008 as a period when global Street Art started to grow with ‘steroids’ to become Muralism. In his article ‘Street Art Is a Period. Period. Or the Emergence of Intermural Art’ on the Hyperallergic website, and in his 2018 Street to Studio book, he writes about Street Art as a period of experimental, pioneering art. He supposed that the term ‘Street Art’ had become radically reattributed by the market, the media, and municipal authorities[1].

In 2008, I felt the same way and watched how many Russian Street Art works were not only unrelated to their social and political context but also unrelated to the city’s dimensional experiences; its architectural forms, for instance. I organized a group show entitled Russian Street Art is Dead, and the exhibition became a final point in the tumultuous era of mid-2000s Russian Street Art. At the same time, the show initiated a broader discussion around the topic of Urban Art in general.

III. The Current Era

The rebirth of Street Art that focused on the political context and was more socially engaged and text-based started growing slowly in the 2010s as a protest mood covered the entire country. In the winter of 2011, compromised parliamentary elections provoked protests across Russia. The protest movement in Russia (2011–2013) was made up of numerous mass political protests by Russian citizens, beginning after the elections of the State Duma in December 2011 and continuing during the campaign for the President’s election.

After presidential elections were held in March 2012, in which Vladimir Putin won in the first round, protesters claimed that the elections were accompanied by violations of Federal law and large-scale fraud. These events were considered the beginning of forming a more active and socially responsible civil consciousness in Russia.

“The artists assess the local issues and use Street Art to a greater extent than previously to attract attention to these homes and to their problems in general.”

Street Art as a grass-roots practice (without any financial or institutional support) began to experience a re-birth in the 2010s – a symbol of building a new society. Several centers outside of the capital began to develop in their own unique ways – places with names like Yekaterinburg, Perm, and Nizhny Novgorod. For example, in Nizhny Novgorod, artists such as Artem Filatov, Vladimir Chernyshov, Andrey Olenev, Andrey Druzhaev, and others have worked very carefully and attentively to interact with the residents thoughtfully.

The artists assess the local issues and use Street Art to a greater extent than previously to attract attention to these homes and to their problems in general. These practices, in turn, are shaping a unique approach to working with city surfaces, a more cautious one that appreciates and endeavors not to violate the existing ecosystem of the city. One could say that today this approach is a style specific to Nizhny Novgorod Street Art and represents a ‘movement’ of socially responsible Street Art.

Many active Street Artists are living today in Yekaterinburg as well. An appreciable number of them are working with text-based and socially engaged forms of art – such as Tima Radya. With his concise philosophical and monumental messages, the artist reflects upon timeless, vital themes and raises the issue of the boundaries between the public and the personal, the political and the social. As a medium for his work, the artist often uses roofs and billboards – surfaces typically reserved for urban advertising. Tima substitutes familiar consumerist messages with his own to shake citizens out of their everyday rhythm. At the same time Tima Radya reflects our soviet history with massive propaganda, which is placed on the roofs of the city’s buildings. Propaganda messages such as ‘Glory of Lenin’ or ‘Peace. Labor. May’ before the 1990s were produced in a similar visual way, which Tima uses now. In his street works, he actualizes our collective memory and gives new meanings.

Also, I want to mention a few artists from Yekaterinburg who are also quite important for helping to capture a sense of Russian Street Art practices today. As many artists are, Slava Ptrk, Vova Abikh, and Ilya Mozgi are focused on using the text form in their work. They are also working to combine visual (figurative) forms with text perfectly; putting messages in the streets that react to urban space or are critiques in social contexts.

These artists also organized a grass-roots Street Art festival in Yekaterinburg called Carte Blanche, which focuses on illegal art in the streets, executed without permission or institutional or financial support. In my opinion, this kind of festival is a response to mural festivals that are prevalent elsewhere, and they represent a more natural progression for the Street Art movement, switching attention away from the legal murals that have grown large on ‘steroids.’

In the Russian capitals of Moscow and Saint Petersburg today you are more likely to see that Street Artists are focusing on the text form, including the artist Maxim Ima, who uses ironic messages in Saint Petersburg and Kirill Kto from Moscow. The works of Kirill are more existential and poetic, often based on reflections of various personal and social processes, sometimes identifying the relationships between them. Kirill’s street comments may be seen as motivational speech to some in the audience of passersby on the street, but not always are the messages obvious to the casual viewer.

Sometimes his message is addressed to a specific person or just to himself. Kirill Kto’s recent works indicate a new phase in his artistic development, critical concerning places (in his own reference system), his own creative journey, and the chosen model of artistic production. In his recognizable cheerful hues, his textual messages are filled with regret and even mourning for the street that has lost its counter-cultural role before our eyes and that he fears will never be the same.

“…it appears to me that Russian Urban Art needs to be radical and pushing for political changes. It needs to be an actual form of the people’s voice…”

Ponosov

Conclusion

Observing all of this, it appears to me that Russian Urban Art needs to be radical and pushing for political changes. It needs to be an actual form of the people’s voice, not institutional art, and probably presented without any support from the government or commercial entities. When I think specifically about Russian Urban Art, it is based on a few of our cultural traditions: literature, conceptual art, folk, and it is influenced by the aesthetics of Lubok and Constructivism/Suprematism. The latter one is more understandable in Europe and the US, a perfect one for export for sure.

This may be why many contemporary Russian Street Artists favor presenting their work against those historical backgrounds; their abstract contemporary geometry unattached to radical messages may seem out of context. I didn’t mention abstract street painters here because from my point of view, contemporary abstract street art is too decorative now, and it’s part of a kind of Zombie Formalism which means it is just a reproduction of nice geometrical forms.

From a historical perspective, I would say that this text-based Street art is more interesting now because it is derived from real life in Russia today. Mixing philosophy, political messages, and humor, it’s something that characterizes Russians as well. At the same time, it makes us far from the West because these kinds of art pieces can be challenging to translate

These new works are, of course, connected to conceptual art – and many Street Artists worldwide have used text for their works. Russian artists who make text-based pieces and who use only the Russian language are creating work that ignores a global audience and focuses on locals only. I think using local language is important for making more precise ideas and messages. It’s also important for Street Artists to create work for the streets where they are from – especially because the Internet is a system for adapting all pictures for a global audience. It is also a place where all identities are dissolving. It is appropriate for specific text-based Urban Art in Russia to focus more on locals; It is more natural and organic when compared to the global movement of Street Art today, which is too often is focused on a global audience.

[1] A political movement for reformation within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union during the 1980s, widely associated with the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his policy of ‘Glasnost’ (meaning ‘Openness’).

Portrait by Joerg Farys.

Heinrich Böll Foundation. Berlin.

Igor Ponosov

Igor Ponosov (b. 1980) is a Russian artist, Partizaning activist, curator and researcher focused on Urban Art. Author of books: Art and the city (Russian: Искусство и город) and Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts. Laureate of The Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Award (St Petersburg).

2005 – 2009 Ponosov published three books on street art in Russia and the ex-USSR.

2011 – 2013 Curated The Wall, a project based in the CCA Winzavod, Moscow. Founded the Partizaning.org website as a platform for exchange among activists, artists and urbanists.

2013 – 2016 Curated the Delai Sam festival, focusing on grassroots iniatives and activism in Russia, and authored Art and the city (2016), for which he received The Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Award 2016 for Best Text on Contemporary Art (St. Petersburg)

2017 Curated group shows in Berlin focused on Urban Art and activism in Eastern Europe.

2018 Published Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts book, launched in Tartu, Besancon, Paris, Helsinki, Krakow, Berlin, Freiburg and Weil-am-Rhein.

2019 Nominated for the Kandinsky prize in Moscow.

Igor’s current title is Cutting the Walls, produced in parallel with his site-specific artworks at CCI Fabrika, Moscow. Featuring texts by sociologist Dmytro Zaiets and art critic Sergey Guskov.

Opinions expressed on BSA Writer’s Bench do not necessarily reflect those of the editors or BSA.

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY

BROOKLYN STREET ART LOVES YOU MORE EVERY DAY